In this, our second instalment in the PMSCs series, Jill Russell will be taking a look at the practical ramifications of logistical contracting in the US armed forces and will argue that contractors are not sufficient for the critical roles they are often assigned.

Birthe Anders

Department of War Studies, King’s College London

PMSCs Series Editor

***

The Private Military Security Contractors Series. Part II:

Overpriced or Out of Sight: What subsistence history teaches us about contractors and tactical logistics at war

by Jill S. Russell

Without much fanfare the American armed forces have over the last several decades shifted responsibility for increasing portions of operational and tactical logistics to private contractors. Focussing specifically upon subsistence, and furthermore on the preparation and delivery of food to the front lines, little concern has emerged over the ramifications of this change in practice. Especially at the tactical level [1] this is a dangerous oversight, for as I will argue here, American experience, both distant and recent, demonstrates that contractors are not sufficient to the critical task of feeding troops at war.

The unreliability of the private sector in tactical logistics was one of the first lessons of American military history. The experience diverged from historical practice, as civilians had long played a part in the delivery of provisions whether as labour, involuntarily with impressments of goods, or enterprise in the food and drink on offer by the local sutler. Considering only the last for the purposes of this discussion, Continental Army leaders might have been able to expect that this character would serve the Revolutionary cause and fill the subsistence gaps the infant army could not handle.

Bordering on catastrophic Revolutionary War subsistence logistics nearly proved the undoing of the Patriot cause. Suffering no lack of provisions extant in the Colonies, plaguing the army’s inability to feed its soldiers were deficiencies rooted entirely in its logistics, from inadequate manpower to a complete lack of professional knowledge and practices. Even still, sutlers could have been the army’s salvation. Unfortunately, in that war, while their propensity to fleece the troops was entirely reliable, their presence where and when necessary could not be guaranteed, in large because the Continental dollars did not interest. However, as the goods were present in the country, it was the want of money in the government coffers that guaranteed the struggle, for were the last not an issue then entrepreneurship would at least have eased many of the logistics challenges.

Thus, weak in the Revolutionary War for reasons of profit, this experience taught that especially at the tactical level, successful logistics could only be guaranteed by the armed forces themselves. The Americans might have been the first to learn this lesson, but the European powers would realize this truth as well over the course of 19th century warfare.

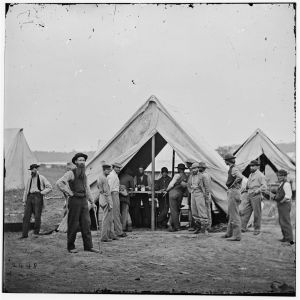

More than a century would pass before this capability was fully developed. The Civil War, for example, was marked by their presence, as sutlers remained an imperfect stopgap when necessary. However, they were never meant to fully serve the logistical needs of the front lines. The long 19th century was a slow march to the military capabilities necessary to manage logistics. Strategic logistics, especially in manufacture and internal transportation, were (and remain) areas in which the private sector outperformed the armed forces.

Cresting in WWII, finally triumphant over most of the challenges, it seemed that the demands of logistics at war had finally been equalled and could soon be mastered. This was not to be the case, and before the lessons of that war’s logistics could be fully learned the apparatus was slowly dismantled. I suspect it was part of the rise of the preference for private sector wisdom regarding what constituted best practices. After all, if America’s businesses could thrive and dominate the global economy then they must have something valuable to teach the armed forces. [2] Except cost savings and efficiency fail war when effectiveness is contested by a determined enemy or the ruthlessness of chance. What works for Wal-Mart does not necessarily serve the Marine Corps.

Unlike in the Revolutionary War, the matters of resources and expertise have not harmed the private sector’s performance in logistics since WWISS. Rather, the altered terms of warfare define the weakness of private contractors in logistics, their failure to adequately serve is caused by risk. By the 20th century the increasing lethality of war meant that unlike the finite and constrained battles of the past, now combat raged night and day, death reigned, but still soldiers needed to be fed. Although durable, portable and ready to eat field rations would be developed, even their delivery to the front lines could be contested. Nor was it the case that these rations could serve for the long term to good fighting effect. That is, no one would starve if there were unlimited C-Rats, but that is not the same as sustaining fighting skill. Accordingly, field rations would never preclude the need for some amount of fresh (or near fresh) provisions to be delivered and prepared for front line personnel.

This significant growth in risk means that even given the premiums paid to contractors, there are levels of personal peril which cannot be mitigated by money alone. Uniformed military personnel accept risk, but they are trained and indoctrinated to do so as part of a group to which they have bonded. In fact, I might argue that it is the matter of risk which defines and separates military personnel from others, and perhaps is their inspiration as well. Absent this trained acceptance, there is a limit beyond which it will remain exceedingly difficult to get contractors to operate effectively.

And yet, by voluntarily choosing the private sector to handle an increasing burden of tactical logistics, by the 21st century’s first wars it has been forward into the past with a return to modern day sutlers and civilians who do the cooking. One might assume that this would mean success all around, as there is no real lack of resources within the nation or government. This has not been the case.

Second chances are always written with new twists, and so this time around it is the government rather than the soldiery that is likely getting fleeced. [3] I suppose that is some consolation. Or it would be except for the unholy gap that has been created at the very front lines and for the smallest units. Coping with this gap, the forces have most often returned to the “old ways.” In OIF and OEF, where the FOB feeding paradigm left small, far forward-deployed units unserved, the answer to the feeding gap has been to send a soldier or Marine to do the cooking. [4] And as American defence budgets are reduced, back in garrison, the days of freedom from KP duty may be coming to an end.

Which raises the question, why has the US returned to a mode of tactical logistics that relied upon the private sector? Logistics love ingenuity. In the private sector this ingenuity improves efficiency and cuts costs. However, in war, it simply worries the problem until the job is done. Rather than a private contractor, the guy who will live and die with the quality of the logistics is like to produce the best results. At least at the tactical level, logistics needs to be returned to the forces. It is part of the fight and needs to be treated as such.

__________________________________

NOTES

[1] There are many ways – depending on the service questioned – to refer to the tasks I consider within the sphere of tactical logistics. The Marine Corps, eg, uses combat service support. For the purposes of this essay tactical logistics refers to the final delivery and/or preparation of goods or services to manoeuvre units for their use.

[2] Of course, if one stops to consider that most of the private sector experience in logistics had been gained in war, that the armed forces had been the trailblazers in such areas, then its presumed superiority must be questioned.

[3] Attempting to unravel the complexity which is the accounting for recent military operations is well nigh impossible. What is clear is that private contractors have not provided the significant cost savings that were promised, nor have they been found to take particular care of the public funds with which they have been entrusted.

[4] I have extensive evidence on one unit’s experience, as well as scattered anecdotal information across multiple deployments. As the problems were structurally determined, it is likely that similar shortfalls were experienced across the deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan.