By Isobel Petersen:

Human migration exists on a large scale across the globe, but in a variety of forms and for a variety of reasons. Conflict is one of the key causes of displacement, which is unsurprising considering the devastating effects of living in a conflict zone: poor health; economic instability; familial tragedy and lack of education opportunities, amongst others.

Today’s conflicts are increasingly asymmetric with non-state armed groups (NSAGs) taking the lead in waging wars, resulting in a multitude of competing factions and loyalties heightening the threat to citizens of a state in conflict. Furthermore, the lines are blurred between combatant and civilian all too easily, normalising both the intentional targeting of civilians as well as their destruction as ‘collateral damage’. During the past 50 years, wars of independence evolved into civil wars, which splintered into NSAGs pursuing their own gains, the targeting of minorities, battles for resources, and border disputes. Today across Iraq and Syria there is a new supra-state crisis with the rise of Islamic State (IS).

In Europe the issue of displaced persons is most visible as thousands cross the Mediterranean into Italy and Greece or by land into the Balkan states. The rate at which they have arrived has doubled in the past year, although Europe is still home to less than 10% of the world’s displaced persons. This is a life-threatening journey with the risk of injury, separation from family, poverty and arrest along the way to a hopefully better life. We are all aware of the tragedies along the southern coastlines of the Med’s beaches, but with the rising political popularity of the European Right there has been a tendency to overlook the more disastrous bigger picture.

The significance of a European Right is that it has become a prominent mouthpiece for anti-immigration, nationalist voices. On the international scale, this has consequently presented the issue of immigration as a concern for the destination countries for immigrants rather than the reasons behind migration. This problem has been exacerbated by the lack of global responsibility to tackle the issue, and focuses instead on the socio-political climate of the countries that have the capacity to assist.

Migrants are displaced peoples, admittedly not always by force, but with sufficient reason to dare to start somewhere unfamiliar and potentially hostile. Displaced peoples can also be refugees, political exiles, stateless peoples and unwelcome minorities. Migration is considered as a last resort, whether to escape persecution, natural disaster, and extreme poverty or conflict zones, and it is not a new phenomenon.

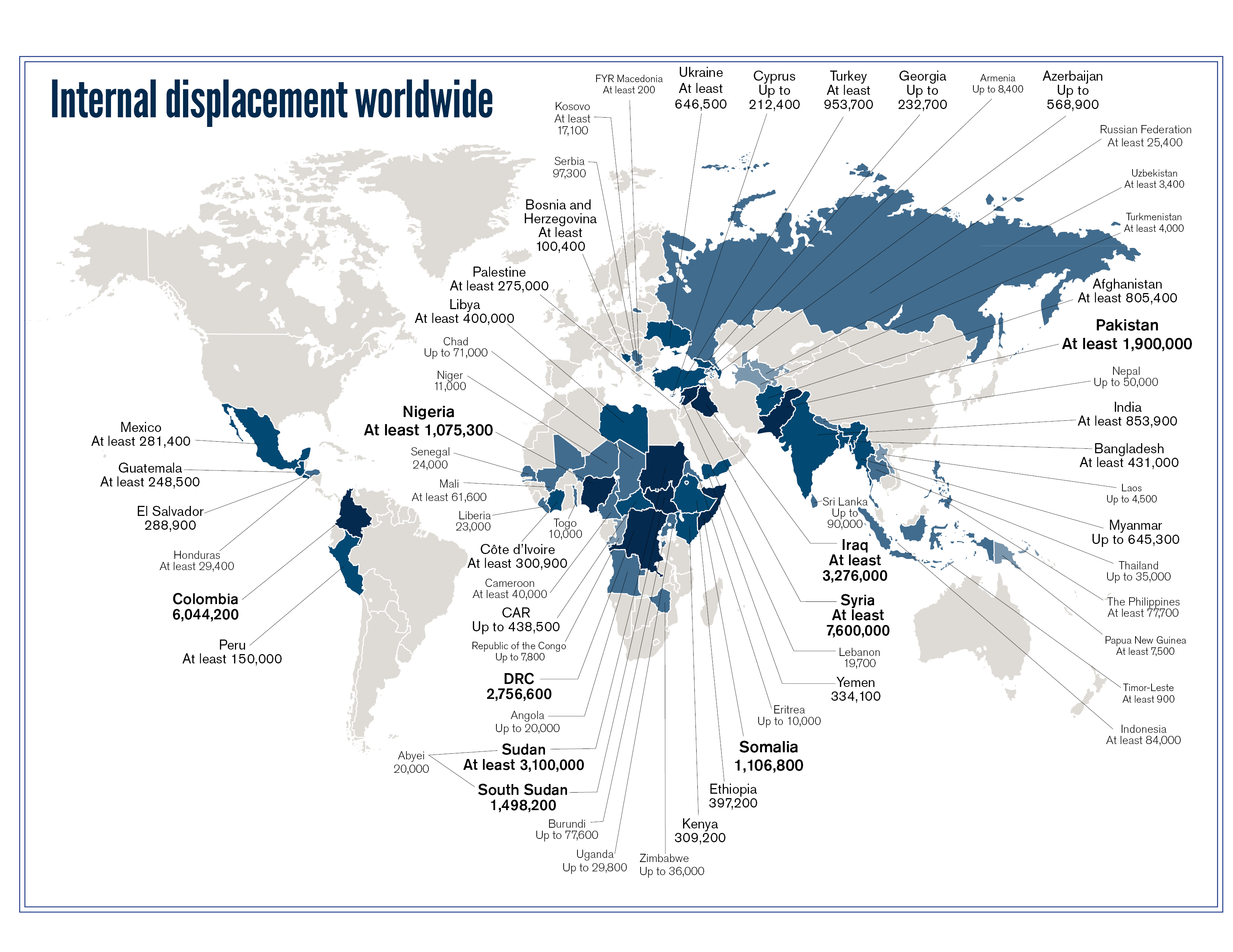

According to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) by the end of 2014 there were 59.5 million people forcibly displaced – that is, involuntarily displaced people. That is only a few million shy of the total UK population. This figure is too large to ignore and states must recognise that they are increasingly going to have to accommodate non-nationals as part of the wider solution to solve the problem. This is arguably precisely why the understanding of migration has narrowed, so much so that the vast majority of those displaced by conflict have been forgotten. These forgotten migrants are internally displaced peoples (IDPs); those who - predominantly as a result of conflict – have had to move within their own countries leaving them economically unstable and at risk from persecution. The issue of cross-border migration is so headline-grabbing that the vast number of IDPs have been pushed to one side, although they are in need of humanitarian assistance too.

A little over a month ago the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) released their latest annual report for the global trends and figures of IDPs. The report makes for powerful and shocking reading, as one realises just how many people are in transitory and volatile living situations within their own country. Across the 60 countries that the IDMC included in the study, there was an equivalent of 30,000 new IDPs every day between January and December 2014, bringing the global total to a staggering 38 million people; a 15% rise from 2013. When one then considers that this is about 65% of all displaced people, it becomes hard to ignore that this is a matter for academics, practitioners and policy-makers alike.

Earlier this month the UN Humanitarian Coordinator for Iraq, Lise Grande, made an urgent plea for £316m in assistance for Iraqis affected by the IS campaign, this includes over 3 million Iraqi IDPs. The financial contribution of international organisations and states is an essential part of the immediate and life-saving relief that people affected by conflict need. However, displacement cannot quickly be reversed or solved simply with funding; it must be a long-term policy movement to help not just the state structure but also the individuals. States impacted by intense conflict are likely to struggle through economic instability and weak state governance, thus making it difficult to provide for their own citizens and migrants.

In a 2009 report published by the International Committee of the Red Cross about IDPs, a key suggestion the organisation made was to assist in providing economic security in areas which are both likely to face the repercussions of conflict and those areas which receive IDPs in order to prevent future destabilisation. Post-conflict peacebuilding is accepted as a role for the UN and its member states; this must include acknowledging IDPs and assisting post-conflict governments in adjusting to the new social, economic and political demands of internal displacement.

The African Union’s (AU) 2009 Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons, (informally known as the Kampala Convention), was the first legally binding instrument specifically catering to IDPs. By December 2014 22 AU member states had ratified it, with a further 20 member states signing it. This is an example of positive action taken by states affected directly, or as regional actors, by IDPs. It particularly reaffirms the obligation of governments to address the needs of those in their own states.

Implementation of concrete change is still, however, a challenge because states hosting displaced persons tend to be fragile, without the economic means to sufficiently address the issue. The Kampala Convention is an example of a decision that needs international support for it to be effectively implemented.

The numbers of IDPs in Colombia are the second worst in the world after Syria with 6 million counted in 2014, although UNHCR has said that may be an underestimate. This is as a result of a 50-year civil war between government forces and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), alongside other paramilitary groups and bandit gangs.

The poor of Colombia are becoming poorer and the ethnic minorities are suffering the most, as they live in the rural areas where most armed conflict takes place. There are legal frameworks in place to respond to internal displacement; however, this is hampered by poor enforcement on the part of the Colombian government, administrative errors, and most importantly a reactive rather than a proactive attitude. The weaknesses in the Colombian strategy of dealing with IDPs demonstrates the all-too-easy potential to provide reactive, short-term responses instead of prioritising a collaborative, long-lasting effort.

Once a ceasefire agreement has been signed, this does not mean that those IDPs who have fled the violence are once again able to continue with their lives. It should not be accepted that forcible displacement is an inevitable result of conflict; a new norm must take hold. Leaving the economic and physical security of one’s home as a result of conflict has long-term consequences for the future stability of a country, jeopardizing sustainable peace. This is the most important reason for why governments of countries with large numbers of IDPs must take the issue seriously and prioritise legal, financial and social assurances in the post-conflict environment. This requires the help of the international community who must continue to contribute to the essential humanitarian needs of those affected by conflict, including IDPs.

Most importantly, however, is the long-term recognition that migrants are not always cross-border refugees who are visible and demand a political response; a political response is needed for the ‘invisible’ migrants who have been displaced within their own countries too. Both issues must be tackled, but the issues are also separate, and demand separate responses.

Finally, it is essential that in countries such as the UK there is an attitude transformation regarding migration, as increasingly our domestic policy and attitude towards foreign relations is becoming narrow-minded and selfish. If this public attitude continues to prevail then there is no hope for a positive British contribution by policy-makers to the international tragedy of forcible internal displacement.

Isobel Petersen studied International Relations at the University of Exeter and is currently reading for an MA in Conflict, Security and Development at King’s College London. Her particular interest is post-conflict resolution with a specific focus on the Arab-Israeli crisis. Isobel is an Editor at Strife.