By: Dr. Charles Schmitz

In Yemen, natural resources do not cause conflicts, people do. The relationship between natural resources and people is mediated by society such that a simple, causal relationship between resource abundance or scarcity and conflict does not exist. In Yemen, scarcity does not cause conflict; in fact, a better case might be made for the reverse, namely that conflict causes scarcity. Conflict drives investment and capital away from the country, destroys productive infrastructure, debilitates the state, and prevents the sustainable management of resources.

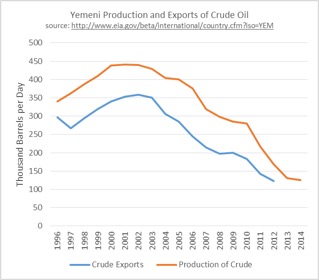

Talk of natural resource scarcity in Yemen focuses on oil and water. In the 2000s, Yemen’s economy and government depended heavily upon oil revenues. About a third of economic output and three quarters of government revenue came from oil.[1] But oil production peaked in 2002 and has declined steadily ever since.[2] What is more, Sana’a is often described as the first capital in the world to run out of water. Water levels in aquifers around the city and elsewhere in Yemen are dropping precipitously. Oil production is falling and water resources are dwindling and in 2015, Yemen collapsed into a devastating civil war. While natural resource scarcity appears to coincide with conflict, the causal relationship between scarcity and conflict is difficult to support.

Unnatural Scarcity

In Yemen, the political dynamics of the Saleh regime created scarcity by driving investment away from the country and failing to manage Yemen’s assets. Yemenis and foreign advisors alike were well aware of two fundamental realities. Firstly, Yemen’s oil and water resources were limited. Secondly, like some of the oil economies of the Gulf States – such as Bahrain, Oman, or even Saudi Arabia today – Yemen needed to invest its revenues from oil to harness the labour of Yemeni’s in economic activities that could produce wealth in a post hydrocarbon economy. Yet the Saleh regime used the economy not for enhancing Yemen’s productive capacities, but for bolstering its political position. It created informal political barriers to entry that allotted key positions atop the private economy to a select group of families; those not included invested their money elsewhere. The lack of private sector development outside of the hydrocarbon sector meant that when oil revenues declined, the economy was not equipped to offer alternative means of making a living. Additionally, the regime also exacerbated tribal and political conflicts preventing the sustainable management of water resources. Thus, the political strategy of the Saleh regime drove the economy into the ground, and created unnatural scarcity by failing to manage Yemen’s resource assets.

The Politics of Aridity

While it is true that water resources in Yemen are very limited, water is also a renewable resource. The majority of Yemen’s water comes from rain, which – given its geographic location astride the Indian Ocean and its mountainous terrain in the West – is plentiful. In addition to the rain, Yemenis exploited groundwater by digging wells. Beginning in the 1950s, but greatly expanding in the 1970s, bore wells enabled Yemenis to exploit groundwater at far greater depths. While traditional social institutions had been developed to regulate the water rights for farmers and herdsmen, they were ill-equipped to monitor and regulate the emerging bore wells that allowed much faster withdrawal rates. Thus, the country’s water problem is not the absence of water, but rather the inability to manage the available resources. In this case, scarcity is a matter of management and state capacity, not a lack of water.[3] When water is managed in a manner that takes into account the technological developments of the last half-century, Yemen’s water resources will consequently be restored.

Additionally, water is not a driver of conflict, at least not directly. Those that make Malthusian arguments about water in Yemen point to violent disputes over wells. While it is true that tribal groups do fight one another over the control of wells, water is not the sole focus of tribal conflict. Rather, the increase in tribal conflict was driven by the politics of the Saleh regime that exacerbated armed conflict in general in the northern highlands.

While tribes in Yemen are long standing traditional institutions that mediate conflict, the fractured nature of tribal society is also prone to conflict.[4] In the far north of Yemen, Saleh used tribal conflict to his advantage.[5] He ruled by the politics of chaos rather than direct control, supporting opposing groups in order to cause and nourish conflict, thereby preventing them from uniting in opposition to his regime.[6]- [7] Thus, conflict among tribes was not caused by resource scarcity, but by a conscious political strategy of the Saleh regime, particularly in the northern highlands. In a slightly different analysis, Lichtenthaeler shows how disputes over land and water in the northern governorate of Sa’adah were driven not only by population increase, but also by the attempts of the regime to alter the political composition of the region’s landowners by installing elements supportive of Saleh.[8]

Oil and Conflict

In our global economy, the relationship between people and the environment is mediated by markets. So while it is true that the quantity of oil produced in Yemen peaked in 2002 and declined every year since, government revenues rose dramatically in the post peak period. Average government revenue from exports of crude oil from 2003 to 2014 was 2.9 billion USD, whereas in 2002 revenues were 1.6 billion USD. Only in 2014 did government revenue from oil exports return to 2002 levels.[9]

The timing of the rise and fall of these oil revenues is important because those making Malthusian arguments for Yemen might point to the correspondence of the decline in oil production with the distinct episodes of conflict in Yemen’s recent history: a secession attempt in the south in 1994; an insurgency in the north from 2004 to 2010; a stubborn civil disobedience movement in the south from 2007; the overthrow of the regime of Ali Abdallah Saleh in 2011; a campaign against al-Qaeda in the south in 2012; and a civil war beginning in 2015 and still raging today. These episodes of violence, with the exception of the war of 1994, do correspond to declines in oil production, but they do not correspond to any scarcity of government resources or recession in the economy. In fact, oil revenues for the government and for the economy were highest in the period of the highest instability: 2004-2011. Thus, something other than resource scarcity was driving these violent outbreaks, namely political conflict over power and the nature of the state.

The war of 1994 is an important example because it is sometimes explained by arguing that the driver of the war was natural resources. However, the war of 1994 resulted from leadership disputes between the former rulers of the southern People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen and the northern Yemen Arab Republic. The two republics were Cold War enemies, but the collapse of the Soviet Union allowed their leaderships to negotiate an agreement for unification. The agreement created a transitional government with equal power sharing while a new constitution was drafted for the united Yemen. The understanding of the leadership of the (much smaller demographically) southern state was that the two former ruling parties would form a coalition government following elections. However, the northern ruling party decided instead to form a coalition government with a third Islamic party in the north that was hostile to the southern socialist leadership.

In the interim period between the unification of Yemen in 1990 and the elections of 1993, significant oil was discovered in the region of the former southern state. Thus, some argued that the driver of the war was northern fear that the south would secede with its newfound oil wealth — a classic resource war. While oil revenues may have enticed the former ruler of the south to attempt secession and thereby secure the survival of his state, the war was not between the north and the south; it was between those that supported unification and those that supported secession. In the south, support for secession was not strong, as many distrusted the old socialist leadership and preferred to live under the liberal state (at the time) of unified Yemen. Moreover, half of the Yemeni Socialist Party also rejected the attempt at secession. In January 1986, the ruling YSP had been rocked by an extremely violent internecine conflict. The losing faction of the YSP and its associated military units fled to the northern Yemen Arab Republic. In the war of 1994, these southern refugees in the north led the war against the secession attempt. Their motivation was revenge. Among the military commanders of the southern forces supporting unity was Hadi, a southerner from the Abyan Governorate and the current president of Yemen. Thus the war was not a case of northerners taking over the south, but northerners and southerners determining the nature of the state and its leadership.

Similarly, the uprising in the south that began in 2007 was not a result of resource scarcity, but a failure of the political strategies of the Saleh regime. Following the war of secession in 1994, Saleh tried to build support in the south. However, rather than rebuilding southern politics, northern supporters of Saleh treated the south as war booty to be plundered. Southerners, including those who rejected secession in 1994, were consequently marginalized; a fate that led them to overcome their many differences in 2007 and unite in opposition to Saleh.

Significantly, the protests in the south came at a time when the Saleh regime was wealthier than ever. In 2006, revenues from state export of crude oil reached four billion USD. In 2007, revenues slid to three billion, but in 2008, state revenues from oil exports reached a record 4.5 billion USD [see charts]. The Yemeni state had more resources than ever, yet irrepressible conflict flared. Saleh tried to use his resources to calm the south by reinstating many southern military officers that had been dismissed after 1994. But the grievances ran deeper than Saleh’s patronage could mollify. Thus, when the state coffers were overflowing, protests raged - scarcity or abundance did not cause conflict, the state’s behaviour did.

Current Conflict

In the current conflict in Yemen, it was the conflict itself that shut down oil exports and drove the economy into the ground. And while natural resources may have played some role (for example, the Houthi movement overran Sana’a with the promise to roll back cuts in government subsidies to oil products), the primary driver is the ambition of the former ruler of Yemen, Ali Abdallah Saleh, now allied with the leader of the Houthi movement, Abd al-Malek al-Houthi, to rule the country. Pitted against their ambitions is the hawkish regime of King Salman in Saudi Arabia who accuses them of facilitating Iran’s influence in Yemen. The Saudi air campaign and the naval blockade of the country crushed what remained of the oil economy and led to dramatic declines in the standard of living as well as a massive humanitarian crisis.

There is, however, one way through which scarcity drives the current conflict: poverty and desperation drives young men to enlist in the many different militias of the competing warlords. The Saudi regime (by proxy), Ali Abdallah Saleh, the Houthi controlled state, and al-Qaeda in the south all pay young men to join the fight. Were these young men not desperate to feed themselves and their families, Yemen’s warring leadership would have much greater difficulty filling the ranks of their militias, and a negotiated settlement would be much easier to accomplish.

The Yemen case shows that the relationship between natural resources and people is mediated by society, and that it is the people that drive conflict rather than resources. In some circumstances, conflicts occur along with resource scarcity, but in other circumstances, resource scarcity accompanies social harmony. People and their politics are the key variables, not the abundance or scarcity of natural resources.

Charles Schmitz is a professor of Geography and a specialist on Yemen at Towson University in Baltimore, MD, USA.

Notes:

[1] Central Statistical Organization (2012), “Annual Yearbook,” Sana’a: Republic of Yemen.

[2] Energy Information Agency (2016), “Yemen,” Washington DC: US Government http://www.eia.gov/beta/international/country.cfm?iso=YEM

[3] Lichtenthaeler, Gerhard (2010) “Water Cooperation and Conflict in Yemen,” MERIP Vol 40, no. 254; Schmitz, Charles (2013), “Geography,” in Steve Caton (ed.), Yemen, Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO

[4] Dresch, Paul (1990), “Imams and Tribes: The Writing and Acting of History in Yemen,” Khoury, Phillip, and Joseph Kostiner (eds), Tribes and State Formation in the Middle East, Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 287

[5] Adel Sharjabi ed. (2009), The Castle and the Chamber: the political role of the tribe in Yemen. Sana`a: Yemeni Human Rights Observer (Arabic)

[6] Blumi, Isa (2011), Chaos in Yemen: Societal Collapse and the New Authoritarianism, New York: Routledge

[7] Phillips, Sarah (2011), Yemen and the Politics of Permanent Crisis, London: Adelphi Books

[8] Lichtenthaeler, Gerhard (2003) Political Ecology and the Role of Water: Environment, Economy, and Society in Northern Yemen, Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company

[9] Central Bank of Yemen (2015), “Monetary & Banking Developments,” January 2015, http://www.centralbank.gov.ye/App_Upload/Jan2015.pdf

[10] Hill, Ginny and Peter Salisbury (2015) Yemen: Corruption, Capital Flight, and Global Drivers of Conflict, Washington DC: Brookings Institute Press

[11] Alley, April (2010) “The Rules of the Game: Unpacking Patronage in Yemen,” Middle East Journal Vol. 64, No. 3, Summer 2010.

Image Source: http://www.zamzamwater.org/yemen-details.php

Charles Schmitz

Charles Schmitz is a professor of Geography and a specialist on Yemen at Towson University in Baltimore, MD, USA.