By Uygar Baspehlivan

Cinema - with its potential for access, emotional resonance, and for creating visually-charged meaning - has been significant in the construction and dissemination of cultural ideas and identities and for the molding of specific, nationalized narratives of historical events in the last century.

During the presidencies of Charles de Gaulle in France (whose strict censorship policies meant the state had a monopoly in the representations of Algeria in France [1]) and Houari Boumédiène in Algeria (who, with the National Liberation Front –FLN- owned and funded almost the entire Algerian movie industry in the 60s [2]), popular cinema functioned simultaneously as a medium of distraction from the post-independence realities both countries were facing, and as a form of nationalist propaganda. In France, this control of the movie industry served to promote a denialist narrative of the struggles and sufferings of the Algerians as well as the dangers faced by the French soldiers in the Algerian War. Similarly, in Algeria, movies of the so-called cinema moudjahid were instrumentalised as means to producing a new post-colonial mythology of the new Algerian nation. In the absence of a strong academic infrastructure or established national history, movies produced by the FLN that told the story of courageous Algerian guerrilla who emancipated the nation from colonial forces became the primary agents for constructing a national history and collective identity. In addition to being a part of FLN’s Islamic Socialist propaganda, these movies also acted as a distraction from problems of corruption, economic crisis and women’s rights that the newly-founded Algerian state was struggling with after its independence.

This article observes how the Algerian war and the colonial experience were perceived and constructed around a binary depicting the visual imaginaries of the colonised and the coloniser.

Umbrellas of Cherbourg

“Umbrellas of Cherbourg”, directed by Jacques Demy in 1967, is a cheerful and romantic musical that portrays the struggles of two young French lovers as Guy – the male protagonist- is drafted to fight in the Algerian war. The movie depicts the love triangle Genevieve (the female protagonist) finds herself in, undecided between waiting for her lover fighting in Algeria or choosing a rich and handsome Roland Cassard who can provide her and her mother with economic stability. As one of the first French movies that attempted to deal with the Algerian War after its independence, the fact that Algeria itself is not even shown in the movie but rather depicted as a distant and exotic place that became an inconvenience and a simple plot point in the love lives of two French lovers is arguably a testament to the reduced status of the war in the French national imagination. War, in post-war French memory, was relevant only to the extent of its effects on the lives of the French, completely disregarding the amount of mutual destruction inflicted during the war.

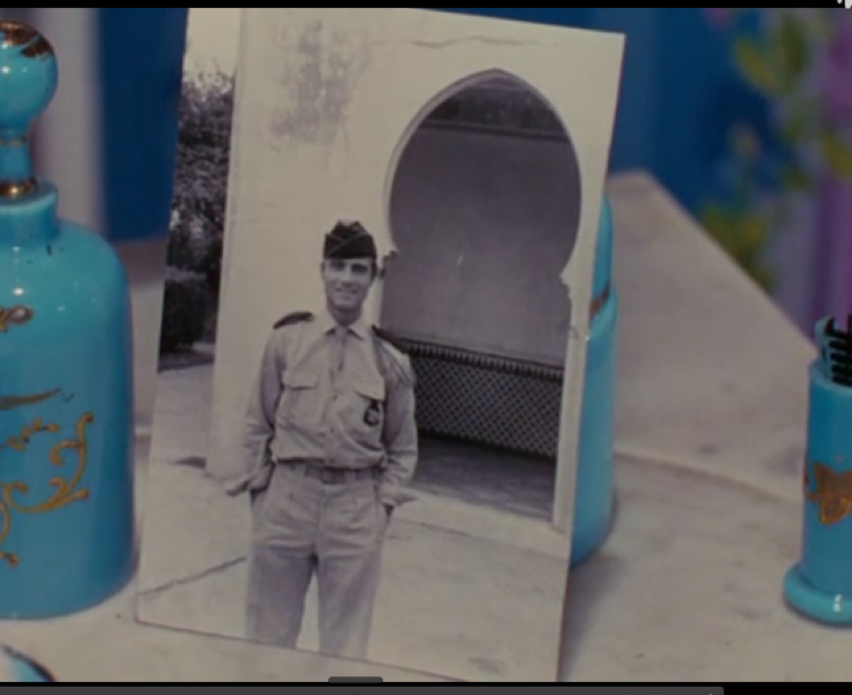

Continuing the colonial tradition of representing Algeria without depicting Algerians, observed in earlier famous colonial films such as L’Atlantide (1921) or Le Grand Jeu (1935), the movie treats Algeria as an exotic yet dangerous landscape. The only shot of Algeria present in the movie is when Genevieve looks at a postcard sent by Guy where he is standing next to a Moorish archway.

In this representation, Algeria is merely a touristic landscape that is protected by the French soldier. Algerians or signs of Algerian life are non-existent. As Guy Austin interprets it aptly; “Algeria and its population are out of sight, through the empty arch, while the photo itself is framed by Genevieve’s letter written naturally enough in French. The war is framed by a French romance, and exists only insofar as it tells about French lovers; Algerians remain invisible - always off-screen.”[4]

The reduced status of the war becomes clearer when Genevieve reads a letter from Guy where he talks about how a patrol was ambushed by Algerians. However, immediately after this anecdote, he emphasises that there actually “is not much danger in Algeria”. The war isn’t important; it is a minor inconvenience that poses little threat to the protagonist’s life. As the audience, we know that he will survive. Not only the suffering of Algerians, but also the danger the French soldiers found themselves in during the war is disregarded and put aside in the movie.

Winds of the Aures

Winds of the Aures (1966), an Algerian movie directed by acclaimed director Mohamed Lakhdar Hamina which won the Palme d’Or prize at the Cannes Film Festival, on the other hand, paints a completely opposite picture of the Algerian war that catered towards an Algerian imagination. A war-time drama about the journey of a mother trying to find her son who was kidnapped by French colonial forces, the 90-minute showcase of Algerian suffering acts as a propaganda tool for FLN’s specific form of Islamic Socialist nationalism. As per FLN’s official policy of bringing about “the restoration of the sovereign, democratic and social Algerian state within the framework of Islamic principles[5]”, the movie’s depiction of how religion and collective Algerian activity worked jointly to bring an end to the century-old colonial rule is an endeavour in constructing a direct link between Islam and Collectivism. As the movie starts with the the adhan (the Islamic call to prayer) suppressed by sounds of conflict, symbolising how colonial domination subjugated the Algerian Islamic identity, it aspires to show how Islam and Algeria’s Islamic identity endured despite the efforts of the colonisers. Representing the Algerian villager as pious and devout, Hamina performs a normative identity making that connects the struggle to religion.

The first thirty minutes of the movie keep up with this collectivist narrative and is dedicated to the daily routines of Algerian peasants working in the village and bringing help to FLN fighters. While French cinema largely attempted to empty Algeria of Algerians, this film defied colonial narratives, showcases the daily lives of Algerian villagers working the soil, producing and consuming. It transformed the exotic landscape of French imagination into a territory filled with indigenous people. This representation of collective activity, playing into the FLN’s socialist Islamic identity, functions in creating a mythology of common collective struggle against colonialism.

Unfortunately, Winds of the Aures can’t escape from the nationalist logic of inclusion and exclusion as it fails to reflect the historical reality of the Algerian war that was rife with internal strife and elite intervention. Disregarding diversity, individuality, and locality in favour of a homogeneous representation of collective peasantry; Hamina uses cinema as an attempt to draw a unified national history. The movie, as it represents a collective struggle of emancipation against the French, therefore, appears to conform to Ella Shohat’s definition of third-world films as using “the expulsion of the colonial intruder” in a cinematic praxis of “national becoming” This depiction of collective wartime heroism - similar to France - diverts attention away from the economic, political and social realities of post-independence Algeria. The glorification of the movie’s female protagonist, as she goes through hell to save his son, for instance, distracts from the fact that many women lost their privileged wartime status after independence and were forced to return to their Islamic domestic lives.

The historical context in which the movie came out is also important, in that cinema is particularly receptive and representative of the cultural environment of its period. A year before the movie was distributed, in 1965, Colonel Boumédiène seized power following a coup d’état. His project entailed a rewriting of Algerian history to provide the country with a unitary national identity. Since there had not really been an Algerian national identity until the 1950s, the peoples living in Algeria found in Islam a central mark of their identity, as it was the element that united them all despite the local differences. Thus, he was able to affirm that Algerians were Muslims and Arabs, a claim that disregarded the wide variety of non-Arab tribes that had lived in Algeria for centuries. This dismissal of the country’s diversity is reflected in the movie itself, which constitutes an attempt to create a unitary, post-colonial national identity, rooted in Islam, in line with Boumédiène’s plan.

The analysis of these two movies reveals that the memory of trauma and conflict can be shaped by nationalist narratives. This constitution and disciplining of memory is primarily exercised by state-controlled or state-censored cinema serving specific narratives regarding the nature, subjects, and motives of the Algerian war. In the end, we observe how both representations of the conflict divert attention from the realities of post-war nation-building. This helps recognise the (re)productive power of visual media in framing and constituting meaning and identity. The struggle for narrative eminence between Algerian and French filmmakers is a testament to the fact that artistic expression is yet another site for political struggles over power and identity.

Uygar Baspehlivan is a graduate of War Studies at King’s College London. He is about to commence his postgraduate studies in Theory and History of International Relations at the London School of Economics. His research interests include nationalism, critical theory, and film theory.

[1] Guy Austin, “Trauma, Cinema and the Algerian War” New Readings 10 (2011), p.18-19

[2] Guy Austin, “Representing the Algerian War in Algerian Cinema: Le Vent Des Aures”, French Studies 61:2

[3] Cited in Guy Hennebelle, “Cinema Djidid”, in Algerian Cinema, p.28

[4] Guy Austin, “Representing the Algerian War in Algerian Cinema: Le Vent Des Aures”, French Studies 61:2

[5] Daho Djerbal, “The National Liberation Front (FLN) and Islam Concerning the Relationship between the political and religious in Contemporary Algeria” The Journal of Sophia Asian Studies No.25 (2007) p.1.

[6] Mani Sharpe, Gender and Space in Post-Colonial French and Algerian Cinema

[7] Mani Sharpe, Gender and Space in Post-Colonial French and Algerian Cinema

Uygar Baspehlivan

Uygar Baspehlivan is a graduate of War Studies at King's College London. He is about to commence his postgraduate studies in Theory and History of International Relations at the London School of Economics. His research interests include nationalism, critical theory, and film theory