By Dean Chen

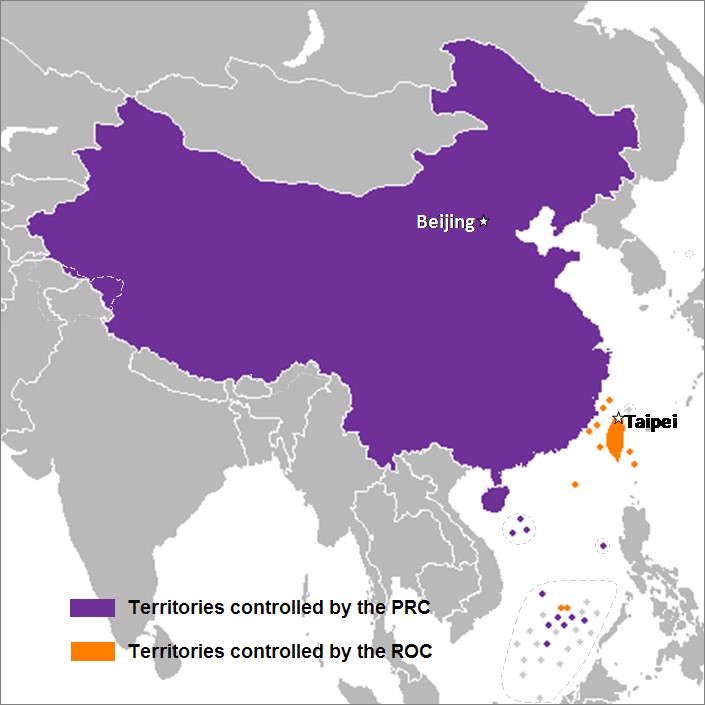

The Taiwan issue is concerned with the political status of Taiwan: whether it should reunify with Mainland China, declare independence as Republic of Taiwan, or maintain the status quo of being de facto independent but de jure remaining within the ‘One China’ framework. While mainstream perspectives focus on Taiwan’s geopolitical significance and power politics involving the People’s Republic of China (PRC), United States, and Japan, this article looks at this issue from an angle of identity mismatch. The ‘national identity’ is concerned with how a nation perceives the ‘self’. The PRC’s identity as the representation of Chinese national rejuvenation with national reunification as an integral element is in contrast with the gradual development of Taiwanese identity as a separate country.

‘Ontological security’ provides inspiring theoretical perspectives to understand this identity mismatch. It is security of the self, the subjective understanding of who oneself is, which enables and motivates actions.[1] For individuals, having relatively stable understandings of the self enables them to make sense of their lives and act independently. When one is faced with ontological insecurity, connected to deep fear of uncertainty, one struggles to ‘get by in the world’[2]. Like individuals, nations also have identities. Similarly, they need certainty and security of the self. In the context of cross-strait relations, i.e. the relations between PRC and Taiwan (officially Republic of China, ROC), with both sides challenging each other’s ontological security, the insecurity of identity within both societies underlies their respective narratives and actions. Therefore, as argued in this paper, ontological security can contribute to understanding entrenched cross-strait divisions.

For the PRC, the ‘Taiwan issue’ is a matter of reunification. Mainland and Taiwan belong to ‘One China’, but are currently governed by two different authorities. National reunification has been an integral part of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) pledge since the establishment of the PRC in 1949. The ‘reunification narrative’ has created strong path dependency, to an extent that any change in direction of the unification policy would seriously undermine the CCP’s legitimacy. This strong commitment to reunification also prevails in the general public. Being taught in school that Taiwan is an ‘inalienable part of China’[3], while the notion of Mainlanders and Taiwanese being ‘compatriots’ is disseminated by official statements and state media[4], it is no wonder that the Chinese public strongly believes in reunification. In fact, Beijing has never ruled Taiwan, and the island basically functions like an independent country. But in the PRC’s official historical narrative, Taiwan was a province of Chinese dynasties, but was lost during the ‘century of humiliation’. This narrative associates this era, stretching from 1840 to 1949, in China with foreign invasion, subjugation and civil unrest. For instance, during this period, Taiwan was allegedly lost the Japanese Empire and separated from the Mainland due to communist-nationalist rivalries. Taiwan is one of the lost ‘seven sons’, a scar of China’s painful memories of colonialism and civil war which should be healed by reunification. In other words, Taiwan’s reintegration is an indispensable part of China’s national identity – a China without Taiwan is incomplete, and China’s ‘national rejuvenation’ could not be done without reunification.[5] Accordingly, the Taiwan issue is a matter of ontological security for the PRC.

On the other side, the story is very different. The political parties and the electorate are deeply divided on the issues of national identity (Taiwanese or Chinese) and Taiwan’s future political status (declare independence or unify with Mainland China). These cleavages created an identity crisis within Taiwanese society. Identity and the future status of the country are highly politicised, often being focal points in elections. Hence, Taiwan’s self-identity bears a conflicting nature and threatens its ontological security. The absence of consensus regarding Taiwan’s status and future not only undermines domestic social cohesion, but also weakens Taiwan’s coherence facing the external world.

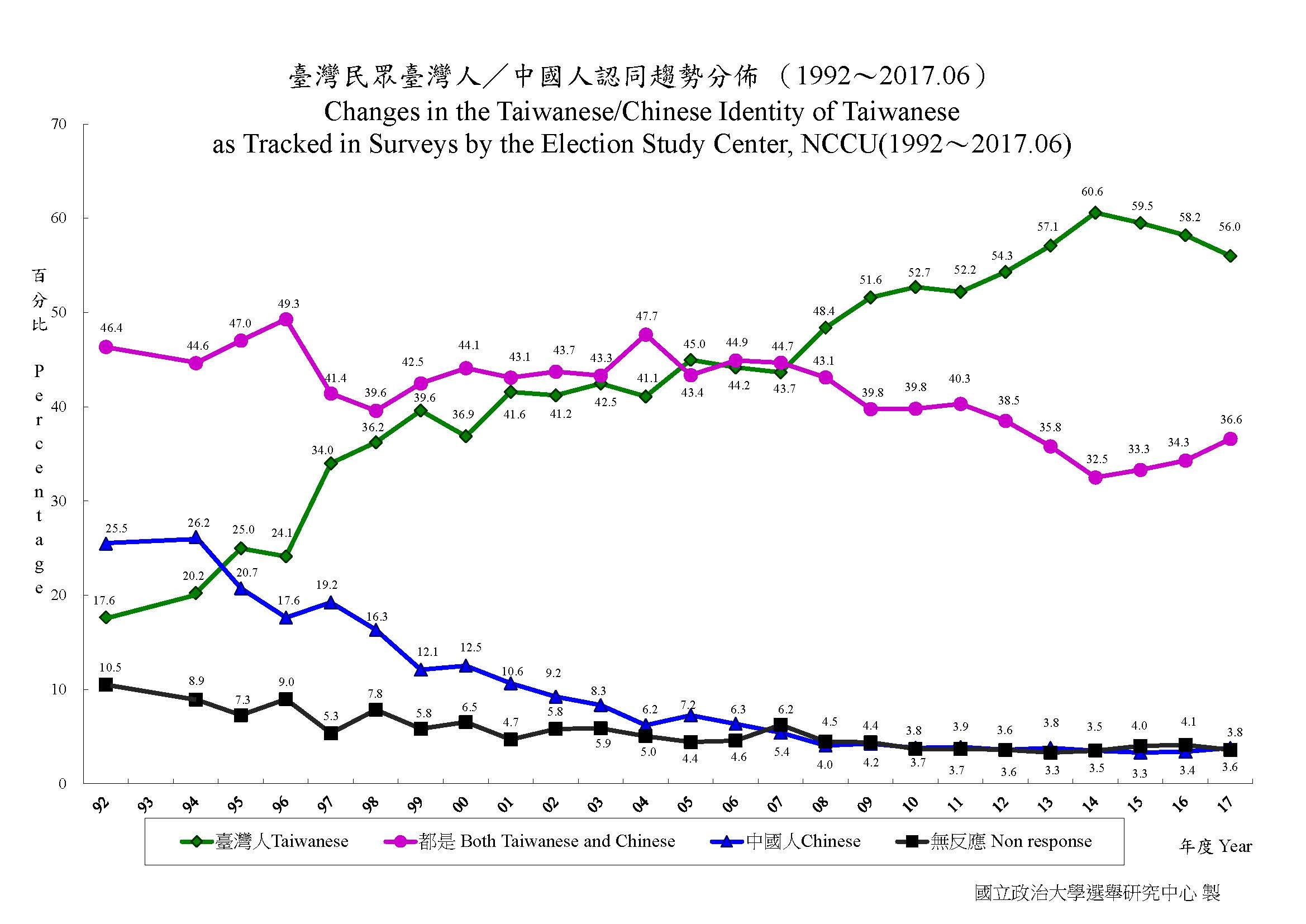

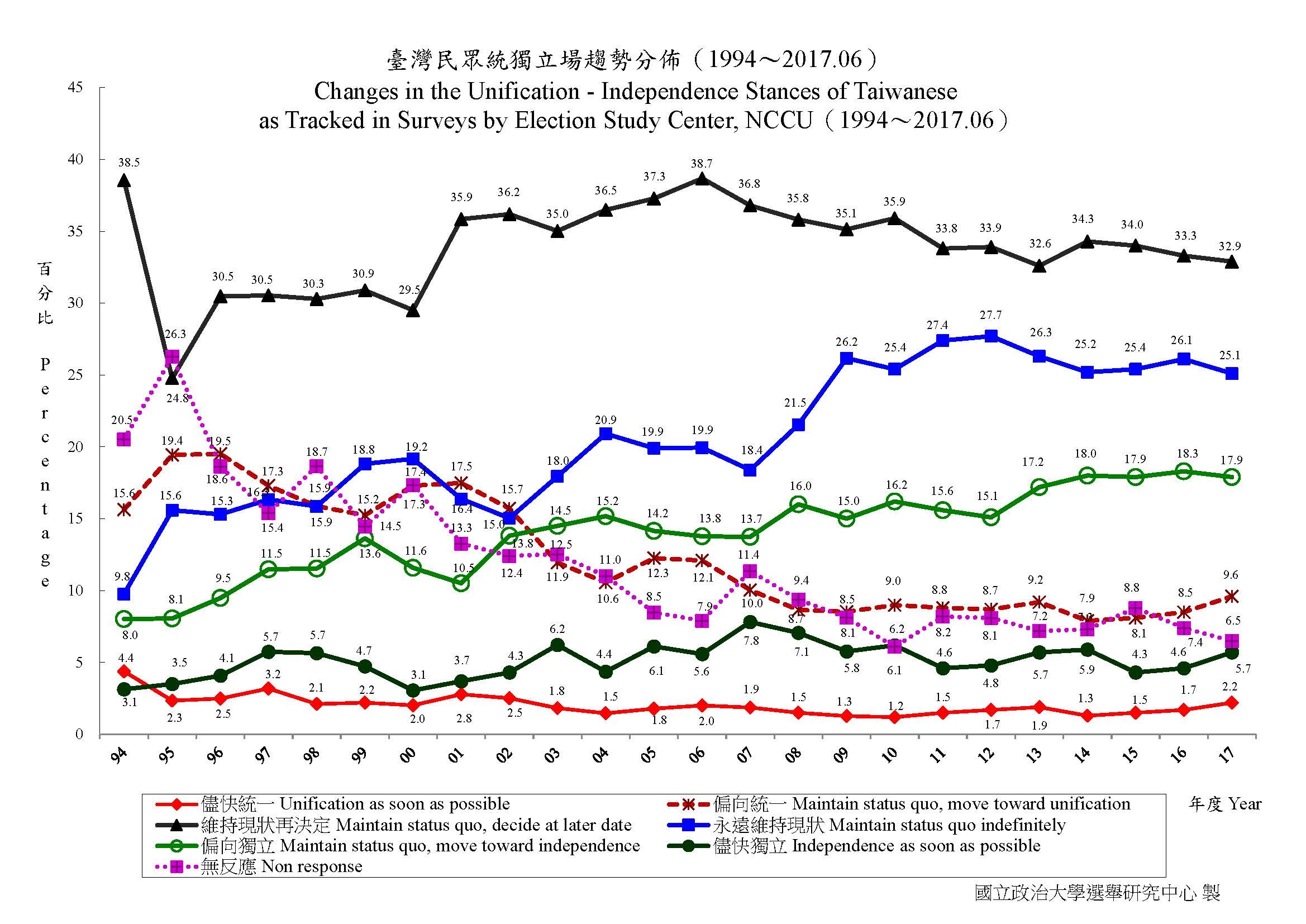

Amid this debate, Taiwan’s public opinion diverged from Mainland China. Although Taiwan maintains the ‘Republic of China’ legal framework, the percentage of Taiwanese identifying as ‘Chinese’ has significantly declined since mid-1990s, while exclusive ‘Taiwanese’ identity has risen significantly. According to a more recent survey, 58% of Taiwanese prefer to maintain the status quo, followed by 23.6% supporting independence, and 11.8% supporting reunification (see chart below[6]). In addition to external factors such as Taipei’s loss of representation in the UN and pressure from the PRC, the domestic process of ‘de-sinicisation’, i.e. the policy of diluting ‘Chinese-ness’ has also contributed to this shift. The then pro-independence president Lee Tung-hui initiated this process in the mid-1990s. For instance, during pro-independence Chen Shuibian’s presidency, between 2000 and 2008, the government changed the history curriculum: Taiwanese history and Chinese history were taught separately, so as to differentiate Taiwan from China. This reflects the narrative of Taiwan as ‘Asia’s orphan’ – ruled by successive external forces but never by the Taiwanese themselves.[7] Pro-independence politicians disseminate the idea of Taiwan, as an immigrant society, is comprised of diverse cultures, rather than Chinese culture as the prevalent one[8]. By diluting the ‘Chinese-ness’ of Taiwan, pro-independence forces seek to distance Taiwan from China. These actions can be explained by the deep controversies in Taiwanese society: in order to assert that Taiwan is different from - and to avoid the unification with - China, especially facing the PRC’s rise as a great power, it is necessary to create an alternative narrative. The manifestation of anti-Chinese sentiment was especially evident during the Sunflower movement in 2014, to protest against a cross-strait trade deal. Activists accused Taipei’s government of colluding with Beijing. More specifically, their concerns were economic integration being used as a mean to integrate Mainland China’s political orbit.

(Credit Image: Election Study Centre National Chengchi University)

(Credit Image: Election Study Centre National Chengchi University)

The identity mismatch linked to ontological security underlies cross-strait relations. For both the Chinese government and the majority of its citizens, Taiwan being a part of China is a given. In contrast, many Taiwanese people no longer identify as Chinese. Deeply engrained identities and narratives on both sides lead to in comprehension and misunderstandings, evident in ‘online nationalism’; Mainland Chinese netizens posted pro-China content on Taiwanese Facebook pages after the 2016 Taiwanese elections. The entrenchment of insecurities about the ‘self’ and conflicting narratives lead to protracting cross-strait division.

So, what is the way forward? To address deep ontological insecurities is not easy. Cross-strait relations in its current tense state is harmful to both sides and regional stability. In order to break the cycle of reinforcing incomprehension and conflict, it is vital to tap into ordinary citizens’ minds and encourage people-to-people exchange. It is only when both sides are open to genuine understanding of each other’s concerns and identities (and why they are so) that Mainland China and Taiwan can transcend this vicious cycle and pursue sustainable peace.

Dean Chen is a third year BA IR student at King’s. His main academic interests are China-EU relations, European integration, Chinese Foreign Policy, and global governance. You can follow him on Twitter on @itsDeanChen

Notes:

[1] Jennifer Mitzen, 2006. Ontological Security in World Politics: State Identity and the Security Dilemma. European Journal of International Relations. Vol. 12 (3): 341-370.

[2] ibid.

[3] Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council PRC, “The One China Principle and the Taiwan Issue,” http://www.gwytb.gov.cn/en/Special/WhitePapers/201103/t20110316_1789217.htm (Accessed December 18, 2017).

[4] ibid.

[5] Li Zhengguang, “Taiwan integral to national rejuvenation,” China Daily, Oct 20th, 2017.

http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/newsrepublic/2017-10/20/content_33509757.htm

[6] Election Study Centre National Chengchi University, “Taiwan Independence vs. Unification with Mainland Trend Distribution in Taiwan 1992/06 – 2017/06,” http://esc.nccu.edu.tw/app/news.php?Sn=167# (Accessed December 18, 2017)

[7] 給下一代的承諾書-十年政綱 (“Promise for the next generation – Ten Year Policy Framework”) http://iing10.blogspot.co.uk/ (Accessed December 18, 2017)

[8] ibid.

Images source:

Image: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/01/China_map.png

Chart 1: http://esc.nccu.edu.tw/app/news.php?Sn=166#

Chart 2: http://esc.nccu.edu.tw/app/news.php?Sn=167#

Dean Chen

Dean Chen is a third year BA IR student at King’s. His main academic interests are China-EU relations, European integration, Chinese Foreign Policy, and global governance. You can follow him on Twitter on @itsDeanChen