By Anna Plunkett

“I have heard it said that we are the uninvited.

We are the unwelcome.

We should take our misfortune elsewhere.

But I hear your mother’s voice,

Over the tide,

And she whispers in my ear,

‘Oh, but if they saw, my darling.

Even half of what you have.

If only they saw.

They would say kinder things, surely.”

-Hosseini, Sea Prayer

Like many others, it was Khaled Hosseini’s novels that brought the vibrancy of conflict alive for me. His books have enraptured thousands, detailing lives under oppressive regimes, insecurity, and conflict. He has detailed the normalisation of violence, the varying levels and stages of fear, and the wide-ranging uncertainty. Though, perhaps more importantly, he’s illustrated the moments of normalcy, joy, sadness, and tenderness that are part of life, even in extenuating circumstances. His stories focus around the family unit and how the developments, challenges, and changes to these fundamental ties transcend the cacophony of chaos that conflict brings.

As such, I was thrilled when, as part of the Literature and Spoken Word programme at the Southbank Centre, Khaled Hosseini presented his latest work – Sea Prayer. A move away from the mountains of Afghanistan that first inspired the Afghan-American doctor to turn his talents to writing. Sea Prayer was inspired by the death of Alan Kurdi who was found washed up on the beaches of Turkey. The image of the three-year-old boy became one of the most iconic images of the Syrian War in 2015 after the boat he and his family were fleeing on capsized just minutes after leaving the shore. The illustrated novel pays homage to those who lost their lives whilst crossing the Mediterranean and narrates the stories of those who survived.

For ninety minutes, Hosseini held the stage in the cavernous Royal Festival Hall speaking to an audience and an interviewer, Razia Iqbal, who were equally rapt and charmed. Born in Afghanistan in 1965, he left in 1976 when his family relocated to Paris for his father’s diplomatic career but was unable to return after the 1979 Soviet invasion. Hosseini spoke about his first-hand experience of becoming a refugee – watching the invasion on TV in Paris as a teenager and realising that his life was about to change, dramatically. From there, he relocated to the US, and attended school whilst speaking no English, and watched his parents struggle to understand and overcome the challenges they now faced in a completely alien situation. It is easy to see the links he draws between his own life and those of his characters.

Hosseini delivered his message clearly. He stressed the importance of storytelling in understanding and overcoming the challenges of the refugee experience. As many qualitative researchers will attest, figures and statistics can miss vital details and experiences that need to be considered when understanding social and political phenomena. Hosseini adds to this, noting how the use of statistics has distanced and dehumanised the refugee plight whereas personal stories can help to overcome the misconceptions and misunderstandings around such complex issues. Storytelling, in Hosseini’s eyes can make seemingly inconceivable situations and choices, such as putting your loved ones on a boat that you know may not make it to the other side, understandable and relatable.

Additionally, drawing heavily on his time as a UNHCR Goodwill Ambassador since 2006 and his trips to Uganda, Lebanon, and Sicily, Hosseini also spoke about the importance of human dignity and why this should challenge our current thinking about the refugee experience. Engaging with numerous refugees and communities who are at different stages in their journey to finding a new home, Hosseini noted three essential rights that he believes are critical when considering the refugee experience: the sanctity of families; the right to asylum; and the right to human dignity.

The first is clearly an issue close to Hosseini as can be seen throughout his work. On the importance of family, he joked that “privacy was another word for being lonely” and family, as he was sure every Afghan in the audience could attest, was everything. Thus, as he rightly identifies, refugees need to be respected – families should not and cannot be separated. The precedent that they can is not only a dangerous one but one that can have disastrous consequences.

The right to asylum is protected under the UN Declaration of Human Rights under article 14. However, as the mobilisation of populations has increased recently and especially since the refugee crisis has hit along the Mediterranean’s shores, this human right has increasingly come under threat. With borders closing to such asylum seekers across regions previously welcoming to refugees, new solutions need to be found. Hosseini remains resolute – he believes that this is not a problem for refugees and asylum seekers alone. He avers that we, as a society, must own and be responsible for guaranteeing this right.

The last of these rights, the right to human dignity, is probably the most under threat among them. With growing dehumanisation of migrants, the rights of these people are often forgotten. People fleeing conflict, in fear of their lives, risking the ‘vessels of desperation’[1] have become caught in a system that rarely provides the materials or opportunities for dignity and purpose. It does not have to be this way – Hosseini acknowledged alternative, progressive strategies being piloted in Uganda where South Sudanese refugees receive plots of land in local communities three days after entering the country.

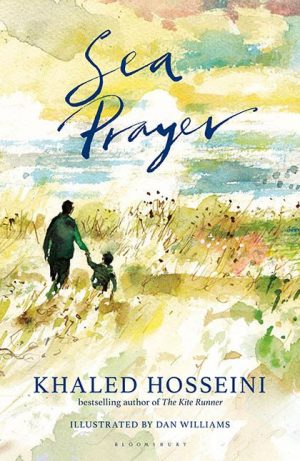

Overall, the book is a slim volume that is exactly what it says on the tin – a prayer from a father to the seas for safe passage of his precious cargo. The short verses bring work in harmony with Dan Williams’ beautiful artwork to bring the hauntingly sad story to life. Hosseini attempts to capture the essence of the refugee’s plight and the loss that comes with it – it is a story Hosseini admits hearing told to him time and again by refugees during his visits with UNHCR. Hosseini noted that storytelling invites listeners to perceive the world from a plurality of perspectives and this, in all its forms, helps overcome the misconceptions and instead build communal understanding. Storytelling may be the bridge over misunderstandings between the two communities – refugee and the local recipient community. However, there is a social obligation by us all that must be realised – the refugee crisis does not belong to refugees. It belongs to us all as a society. We must improve our collective action to ensure that human dignity is guaranteed to all people, including those refugees who so clearly deserve it.

Khaled Hosseini presented Sea Prayer in conversation with Razia Iqbal at the Southbank Centre on the 4th September 2018. Sea Prayer was released for sale in the UK on the 30th August 2018, and in the US on the 18th September 2018. It was written in collaboration with the UNHCR and illustrated by Dan Williams.

Anna is a doctoral researcher in the Department of War Studies, King’s College London. She received her BA in Politics and Economics from the University of York, before receiving a scholarship to continue her studies at York with an MA in Post-War Recovery. She was the recipient of the Guido Galli Award for her MA dissertation. Her primary interests include conflict and democracy at the sub-national level, understanding how minor conflicts impact democratic realisation within quasi-post conflict states. Her main area of focus is Burma’s ethnic borderlands and ongoing conflicts within the region. She has previously worked as a human rights researcher focusing on military impunity in Burma and has conducted work on evaluating Bosnia’s post-war recovery twenty years after the Dayton Peace Accords. You can follow her in Twitter @AnnaBPlunkett

Notes:

[1] Hosseini in conversation about the boats used to cross the Mediterranean at the Southbank Centre, 4th September 2018.

Image Source:

Banner: http://www.unhcr.org/khaled-hosseini.html

Image 2: https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/sea-prayer-9781526602718/