by Matthew Ader

Scholars and policymakers around the world are turning to history to understand how to navigate the onrushing collision between the ailing United States of America and an increasingly assertive China. The most famous example, expounded upon at length in Graham Allison’s Destined for War, is the clash between Sparta and Athens as documented by Thucydides. However, the most recent hegemonic transition, that of Britain to the United States, deserves significant attention – it is well-sourced, exhaustively documented, and involves national actors still relevant today. That makes it a valuable case study.

However, little work has yet been done to model this period in a way, which would allow the clean transfer of lessons learnt to the modern context. Even Kori Schake’s Safe Passage, written explicitly with the intent of informing Sino-American competition, is an excellent history before it is a work of political science. The relative paucity of overarching models means that policymakers must either fall back on heuristics or delve into intricate historical details.

This article attempts to split the difference by deriving a broader model of hegemonic transition from the circumstances of the Anglo-American case, with the hope that it will ease comparative work between the historical and contemporary situations.

I argue that the transition can be broken down into five distinct phases:

- Potential for competition (1756 – 1823) – the United States begins to grow in capability, but Britain is not yet aware of the potential threat.

- Recognition (1823) – Britain recognises the United States as a potential threat.

- The window of opportunity (1823 – 1914) – Britain conducts policy to (in most cases) conciliate the United States as the two nations move towards parity.

- Moment of transition (1916) – the United States surpasses Britain, as a result of British losses and American industrial growth during the First World War.

- Settling into a new order (1917 onwards) – the United States becomes the new global rule-setter, and Britain adjusts its position accordingly.

The United States’ growth in power began before the American Revolution, with the Seven Years War and American independence, but a combination of internal weakness and British distraction with eastern conquests and ambitious Corsicans – not to mention America’s poor performance in the War of 1812 - meant that it took until the 1820s for senior British officials to directly recognise the future potential of the United States as a major disruptive influence. Notably, and seemingly uniquely in terms of hegemonic transitions, this was recognised long before the United States even began to approach military parity with Britain. This may be due to traditional British lack of confidence in its own power, and also the naval character of said power – as Lord Palmerston observed in 1858, the simple reality of American geography rendered it invulnerable to British domination even in the absence of a major US force.

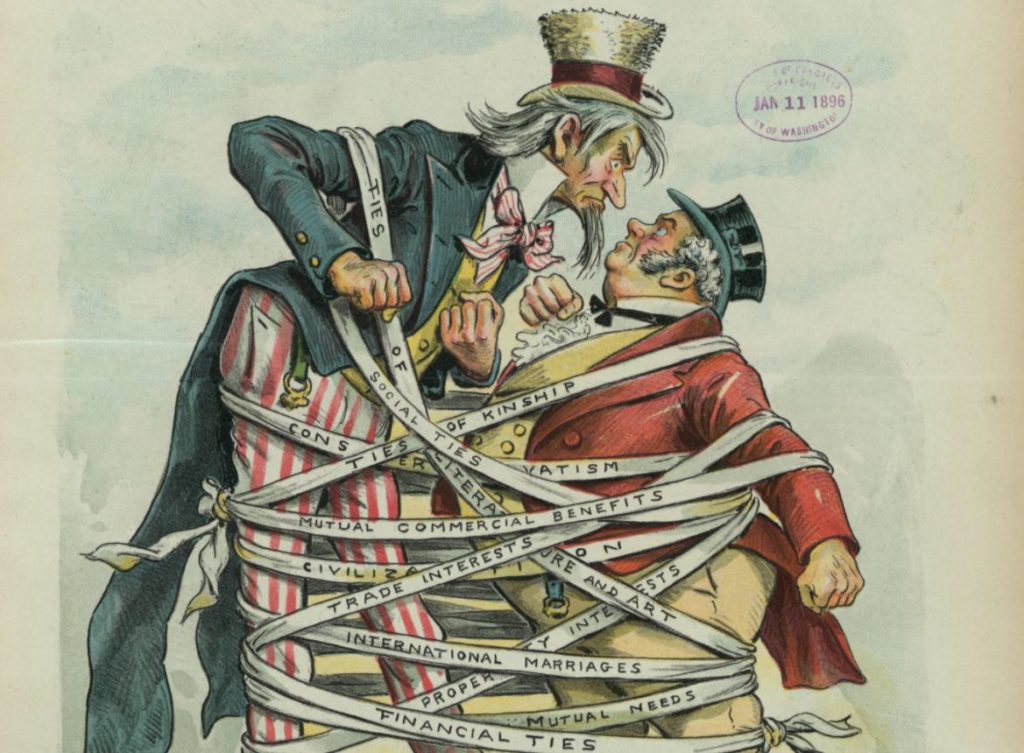

Given that Britain recognised the potential for competition relatively early, they had a large window of opportunity to apply policy. Instead of launching a preventive war, which would have been ineffective given the fact that Britain could not achieve lasting dominance over the United States, they pursued a consistent policy of conciliation. During the Oregon boundary dispute (1846), the Trent Affair (1861), and the Venezuelan Debt Crisis (1895), among other crises, Britain de-escalated even when it held the upper hand in coercive force. British bankers and merchants were encouraged to invest in the United States, even as propaganda about a joint Anglo-American destiny, linked by shared Anglo-Saxon heritage, percolated into American culture.

This was sagacious policy and was enabled in large part by the early recognition of the potential threat the United States posed and subsequently extensive window of opportunity. Given 80 years, most diplomatic relationships can be transformed in major ways – this is much less viable over shorter time frames. The result was that at the moment of transition, towards the end of the First World War – as British policymakers acknowledged that American industrial power so outmatched their own that America held the upper hand in any interaction, as was evidenced by the Paris Peace Conference and the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty - the United States looked on Britain not as a weakened rival, but as a culturally, economically, and at least somewhat strategically aligned partner. Debate persists, however, on the specifics of the Anglo-American transition of power, with many scholars placing it in 1945. However, I would argue that the passage happened in 1916 and was already visible at Versailles. Nevertheless, Britain continued to play a global role arguably disproportionate to its means. The USA, in turn, did not emerge as a hegemon until after the Second World War.

Why A Model?

Given that the historical record exists, why would a model of that transition be helpful? Principally because it allows clearer comparative analysis and the codification of lessons learnt.

First, in terms of comparative analysis, we can transfer this model to Sino-American relations relatively clearly. The potential for competition existed throughout the 1990s and 2000s as China grew in power, but the distracted United States only recognised the threat in 2009 with the Pivot/Rebalance to Asia. Others would argue that this recognition came even later, with the American declaration of China as a near-peer competitor. The United States is now in the window of opportunity vis a vis China, as the relative gap between the powers narrows, and must implement policy to forestall or cushion its decline. If current trends continue unabated, there will be a moment of transition, either when China peacefully surpasses American power; or when its aggressive moves run into a mutual red line.

Rather than attempting to draw difficult comparisons based on historical events in the Anglo-American relationship, the existence of the model allows references to history without getting lost in the details. Similarly, the model allows a clearer discussion of lessons learnt. British success stemmed in large part, I would argue, from early recognition of the American potential as a competitor. Others might suggest it was the result of effective policy within the window of opportunity. A model equips us with a common vocabulary to discuss a difficult topic.

This is not, of course, perfect. The model itself is applicable to Anglo-American hegemonic transition, and I believe Sino-American too, but it carries with it the weight of hindsight – assuming as it does that China will at some point fight the United States or move past it in some peaceful yet vital way. Equally plausible is the idea that China may fall short of hegemony, not due to American action within the window of opportunity, but internal socioeconomic weakness. Another possibility not fully incorporated in this model is that the United States and China may reach parity and remain there for a long period, with neither able to act as a hegemon. And, of course, in the general sense, having an avowedly simplifying model often makes things more complex, not less.

Despite that, given the growing importance of hegemonic transition, it is important to ensure rigour and clear communication in debates around it. This model, or something like it, may go some way towards helping in that effort.

Matthew Ader is an undergraduate student in the Department of War Studies at King’s College London with an interest in climate change and grand strategy. He tweets occasionally from @AderMatthew.

Matthew is a third-year student doing War Studies. He has worked as an intern in a number of security consultancy firms. His academic interests gravitate loosely towards understanding challenges and opportunities for Anglo-American strategy in the 21st century (and also being snide about Captain America’s command ability). He is an editor at Wavell Room, among other publications.

You can follow him on Twitter: @AderMatthew.