by William Reynolds

“Everybody would just love to see one of them sunk…that’s what we’re here for! Sink the bloody things!”

– Royal Navy crewman interviewed on HMS Bacchante (1975)

“Gunboats? Threatening the civilian citizens of NATO ally over fish? Have you lost your fucking minds?”

–Victoria Freeman, Twitter (2020)

Introduction

Although separated by 45 years and vast differences of opinion, the two statements above accurately reflect what can only be described as a clash of competing fantasies currently taking place on social media. A recent article in The Guardian highlighting the readied usage of four Royal Navy vessels to patrol British waters in the case of a No Deal between the European Union (EU) and United Kingdom (UK), and its comparison to the Cod Wars, has proliferated commentary on the case of fish and how best to manage them.

Immediately after The Guardian’s publication, a number of well-respected academics and practitioners waded into the debate. Sir Lawrence Freedman, also alluding to the comparison made, reminded us that Britain ‘lost’ all three of the Anglo-Icelandic fishery disputes, coined the Cod Wars (1958-61, 1972-73 and 1975-76). Elisabeth Braw couched the news in deterrence terms, referring to it sounding “like a parody”. By contrast, the various jingoistic calls for force through attacking retweets of MP and Chair of the Defence Select Committee Tobias Ellwood’s exasperation very much mirrored Brexit MEP Robert Rowland, who in 2019 called for any foreign fishing vessel in British waters be “given the same treatment as the Belgrano!”

In reality, and perhaps a consequence of the lack of nuance on social media, both ‘sides’ support arguments that can only be described as simplistic in the extreme. First, and foremost, the Cod Wars are not an appropriate comparison for the current situation around UK waters, and The Guardian article has much blame to shoulder for alluding to the connection. Whilst the operational, day-to-day activities that took place during the successive ‘wars’ may offer some insights into the UK-EU tensions, strategically both cases are in very different places. Secondly, the narrative regarding the ship deployments itself is false. Rather than being seen as deployment in response to the tensions, the Fishery Protection Squadron should instead be seen for what it really is, an expansion of already conducted duties by default.

The Cod Wars - A ‘storm in a teacup’

As seen from the commentary on social media, the Cod Wars have clearly captured the imagination of the British public in lieu of raising tensions vis-à-vis fishing around the UK and a Brexit Deal. It is somewhat fitting that the term ‘Cod Wars’ was in fact coined by Fleet Street in September 1958. As yet again, it is the British media who is raising its ghost for today’s issue. However, the comparison is deeply flawed. If one had to identify the core elements of the three Cod Wars, themselves individually distinct in character, it would be the asymmetry of commitment between Iceland and Britain and the political environment, both international and domestic, that these conflicts occupied.

Asymmetry of commitment played a huge role in the dynamics and eventual outcomes of the three Cod Wars. The already struggling British trawling industries of the mid-1950s, and by extension the communities in Hull and Grimsby, were heavily reliant on the fisheries within fifty nautical miles of Iceland, with such an extension reported in 1971 by the Under-Secretary to the FCO Anthony Royle as likely to lead to a decrease in catches by forty to sixty per cent. Whilst the First Cod War’s (1958-61) extension to twelve nautical miles from four was worrying, it was the Second War (1972-3), and the fifty mile extension, which really started to hurt the industry. By the Third Cod War (1975-76) it was understood that a 200 nautical mile limit, which was the planned final extension by Iceland, would kill the industry altogether.

However, the British fishing community as a whole only contributed to around one per cent of the entire British economy during the period of the Cod Wars. By 1956 the trawling industry was no longer profitable to the British state, Britain did not fear damage to the British economy as a whole, rather localised mass unemployment, which was still a fair concern. Thus, preventing the communities from automatically going on social welfare benefits (the Dole) by default was the key objective of the British state. In contrast, the fishing industry was viewed as a real existential issue for the Icelanders. Around 89% of Iceland’s export involved the industry, and there were very real fears that overfishing would see this collapse. Nor was this fear unfounded, when herring suddenly disappeared from Icelandic waters in the mid-60s, it led to a drop in real per capita income by sixteen per cent. It was with no embellishment that a Panorama team based in Iceland (1972) stated: “Icelanders are haunted by the fear that one day the fish will no longer be there.”

This asymmetry of commitment permeated all the actions taken by both states, particularly in domestic politics. In essence, whilst the British government was more beholden to its fishing communities, rather than the wider public, the Icelandic government’s legitimacy in the eyes of the entire public was founded on extending its limits and holding them.

The Icelandic population, around 200,000 in 1956 (and smaller than the 300,000 of Hull) supported five viable political parties and five newspapers. Thus, when the Cod Wars ignited, this politically engaged population was like the fuel for a lighted match. Quite quickly, nationalist rhetoric portrayed Iceland as the plucky ex-colony fighting the colonialist power, with each of the conflicts later compared to the Battle of Britain in terms of their cultural significance vis-à-vis a ‘national struggle’. This nationalist sentiment quickly spiralled out of control for Iceland’s Politicians. In 1958, when the British side reached a compromise in Paris, the Icelandic Foreign Minister stated [N]o Icelander will even consider a further discussion about settlement…”. This led the Icelandic representative at Paris to grumble that “everyone in Reykjavik has gone stark staring mad.” Indeed, such domestic pressures would be prevalent throughout each conflict. In 1975 Prime Minister Hallgrimsson felt compelled to deploy the Coast Guard due to domestic ire, despite favouring a negotiated settlement.

By contrast, while the British government was often compelled by the British trawling community to deploy ships, the government ultimately held on to control. This was highlighted by the three successive de-escalatory measures, one for each conflict, which, in essence, capitulated to the Icelanders. As the conflicts escalated, successive British governments ultimately decided the fight was not worth the cost, both politically and economically. After all, the wider British public was rather apathetic to each conflict, and economically, that 1%, was a drop in the water. Perhaps the best example of the British government’s ultimate control, despite domestic pressure, was that Tony Crossland, the Foreign Secretary who hashed out the final Cod War agreement, was the MP for Grimsby!

Send in the gunboats! False comparisons invoked by Brexit

Therefore, the driving forces behind the three Cod Wars hold little water when it comes to comparisons with the fishing disputes between Britain and the EU. Without even touching upon the wider political factors such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) and the Cold War, it is clear that Britain and Iceland were playing with cards, and for a prize, of considerable difference to Britain and the EU in the modern day. Basically, the actors, the geography, the time and space, are all different today.

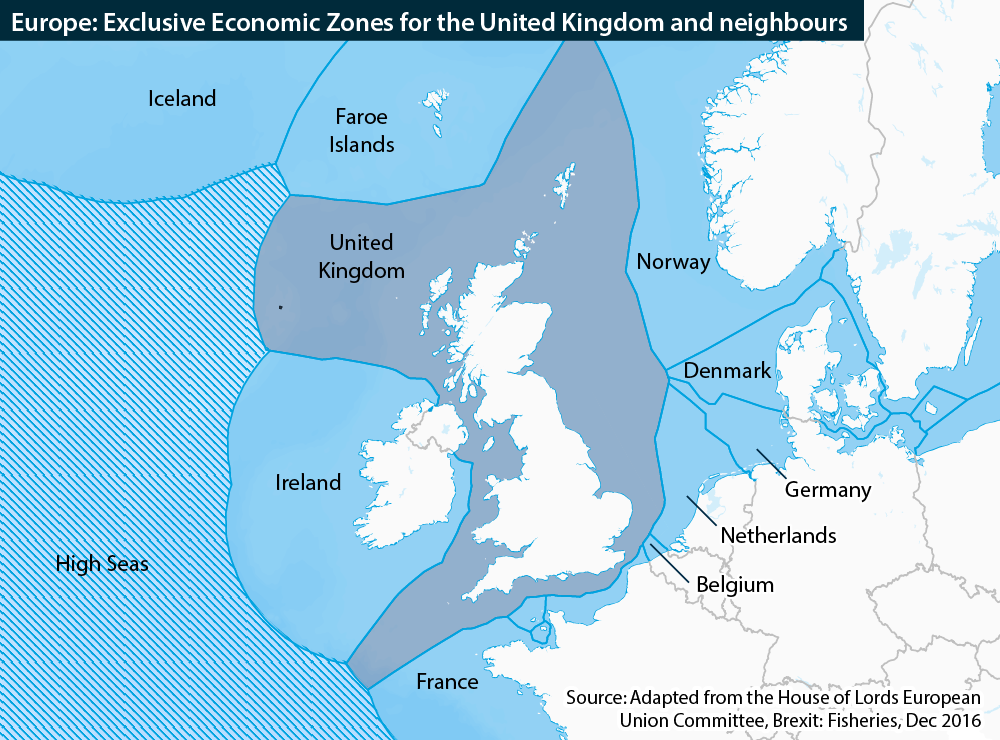

Chiefly, Britain is now interacting with waters that, even as a member of the EU, are legally its responsibility. Concepts of 12, 24 and 200 nautical miles, as enshrined under the United Nations Convention for the Law Of the Sea (UNCLOS), were still under intellectual development during the three Cod Wars. Today, they are foundational. This change automatically places the UK on a more even footing when it comes to levels of commitment present in order to achieve a favourable UK outcome. Whereas the conflicts with Iceland were ultimately some 1,600km away from London, these waters are figuratively, and legally, Britain’s ‘back yard’. As a result, Boris Johnson’s government has to consider a playing field, with its advantages and disadvantages, which are radically different to his predecessors of Harold Macmillan’s, Harold Wilson’s, Ted Heath’s and Jim Callaghan’s, former PMs at the time of the Cod Wars. One could even suggest the British playing field looks far closer to what Iceland would have seen back in the day. This is not to say the various European states do not have equal concerns, after all, the waters are equally important to them. But in this case, the Britain-Iceland asymmetry in concerns and distance is no longer present, making the comparison poor.

Secondly, whereas the Cod Wars required a ‘deployment’ of naval vessels to far waters, what follows after 1 January 2021 if no deal occurs would, in fact, be an extension by de facto. River class naval vessels who, alongside their forbearers, have been doing Fishery Protection since 1586, and includes medical and technical support for fishermen, search and rescue and liaison with other constabulary forces. Fundamentally, the four River-1 class patrol vessels are doing the exact same job as the Japanese Coast Guard, French Maritime Gendarme and Icelandic Coast Guard, with similar vessels in terms of weaponry and tonnage to boot! British vessels may be naval, but that is a quirk of history rather than a conscious decision.

Thus, it is wrong to say that these vessels are being deployed, when in actuality they are already present. Rather, if the waters revert to purely UK jurisdiction after the end of January 2021, their existing commitments will simply expand by de facto. This is not an aggressive deployment of gunboats, ready to ride off French Gendarme and ‘torpedo’ French fishing vessels, it is an expansion of commitment in line with Britain’s responsibility to conduct effective Maritime Governance, including not just Law and Order, but combatting pollution and search & rescue operations. For the UK to not do this would be an abdication of its responsibilities under UNCLOS.

Conclusion

Whilst there are many more factors and arguments that could be drawn upon to highlight the false mindset of comparing the current disputes with the Cod War, it is clear that the core elements of the three Cod Wars, asymmetry of commitment and political environment, are rather different to that of today.

Moreover, not only are the elements different, but the more tangible structural causes are equally different in flavour. This is not a deployment to waters over 1600km away, nor is the UK legally in a more nebulous environment. Furthermore, no deployments are necessitated, as the Fishery Protection Squadron has been in place in these waters since at least the 16th century.

This may all seem pedantic, but as highlighted by the Icelanders, rhetoric matters. If framing it in terms of the Cod Wars, we risk not only underestimating Britain’s natural position but additionally polarising the British population further, as both more nationalist ‘Brexiteer’ sentiments and false fantasies from the opposing, predominantly ‘Remainer’ sider entrench further and clash in increasingly heated discussions. If one lesson can be learned from all this, it is perhaps a more nuanced understanding of the historical case studies that are being used. Just as Brexit is not a rehash of the Second World War, the fishing dispute is not a repeat of the Cod one.

William Reynolds is a Leverhulme Scholar Doctoral Candidate with the Centre of Grand Strategy and Laughton Unit in the War Studies Department, Kings College London. Graduating with a Bachelor’s in War Studies, and Master’s in National Security Studies from the same department, William’s interests have evolved from military history to maritime security and grand strategy, particularly regarding Britain and the Indo-Pacific area. William’s research focuses on British and Japanese interactions in the grand strategic space post-1945. Over the years, William has conducted work with the King’s Japan Programme regarding maritime security in the Indo-Pacific region, with a particular focus on the maritime arena as a domain for interstate interactions. This has included United States Navy carrier and amphibious group deployments, Royal Navy deployments in the region from 1998 and, more recently, Chinese and Japanese Coast Guard procurement, history and interactions in the East China Sea. Outside of University, he has worked as a research analyst for an IED threat mitigation company, with a focus on Europe and Syria. You can follow him on Twitter @war_student.

William Reynolds is a Leverhulme Scholar Doctoral Candidate with the Centre of Grand Strategy and Laughton Unit in the War Studies Department, Kings College London. Graduating with a Bachelor’s in War Studies, and Master's in National Security Studies from the same department, William’s interests have evolved from military history to maritime security and grand strategy, particularly regarding Britain and the Indo-Pacific area. William’s research focuses on British and Japanese interactions in the grand strategic space post-1945. Over the years, William has conducted work with the King’s Japan Programme regarding maritime security in the Indo-Pacific region, with a particular focus on the maritime arena as a domain for interstate interactions. This has included United States Navy carrier and amphibious group deployments, Royal Navy deployments in the region from 1998 and, more recently, Chinese and Japanese Coast Guard procurement, history and interactions in the East China Sea. Outside of University, he has worked as a research analyst for an IED threat mitigation company, with a focus on Europe and Syria. You can follow him on Twitter @war_student.