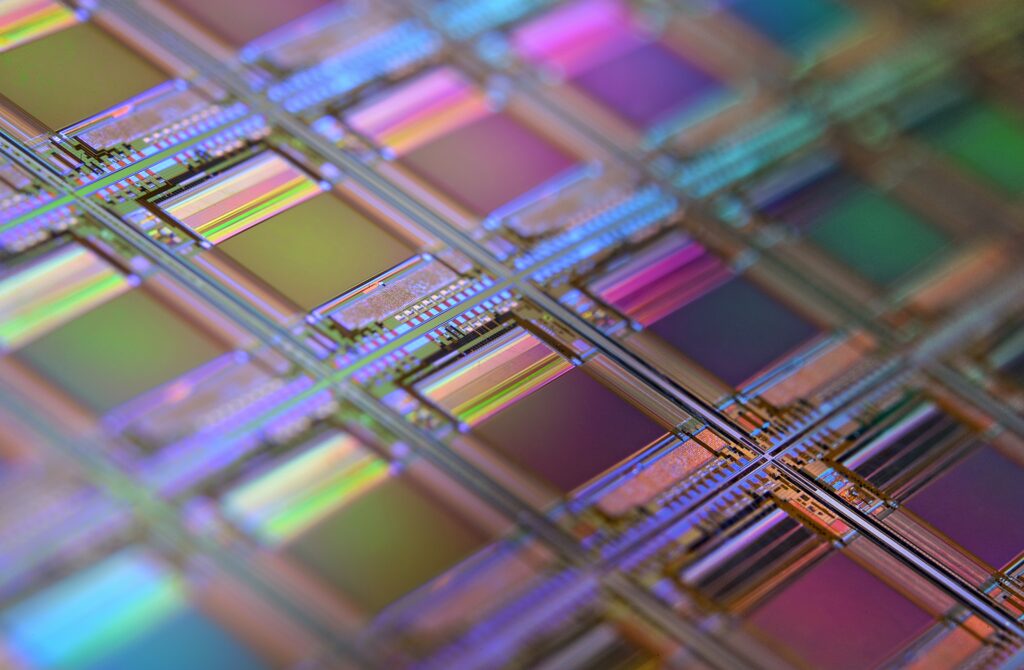

Microchips, also called semiconductors or integrated circuits, can be thinner than a human hair and smaller than a postage stamp, but their power can be immeasurable. They play a significant role in the advancement of the consumer technologies sector and, most importantly, in the development of more sophisticated branches of technology with potentially significant implications for national security, such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) and quantum computing. Therefore, although domestic and foreign policy might not always be connected, in the case of the U.S. semiconductor industry, domestic decisions are vital both for U.S. national security and for the evolution of great power relations in general, and U.S.-China relations in particular.

The largest chipmaker in China, the Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), was added to the U.S. Entity List by the Trump administration in late December 2020 as a final move of the toughest measures taken towards Beijing, fearful that the Biden administration would soften the policy towards China. Biden, however, has not only dismantled such tough decision on the technology front, but his administration is also working on domestic measures around the semiconductor industry that will be central to U.S.-China technological competition.

In September 2020, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021 (NDAA) came into law, authorising investments in both domestic chips manufacturing incentives and in advanced microelectronics research and development. Soon after Biden took office, the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) followed up by stressing the need for the new U.S. administration to prioritise funding to such provisions. This came in light of the sharp decline in the U.S. share of the global chip manufacturing, which can affect the U.S. ability to produce newly advanced technologies vital to strengthen both U.S. military capabilities and its great power status overall. In fact, although the United States is the currently the global leader in semiconductors, owning around 47% of the global chips market share, U.S. chips manufacturing has been decreasing, and this might affect the American leadership in the sector already in the medium run. According to SIA, while in 1990 the United States accounted for the 37% of the global chip manufacturing, in 2020 this share has fallen to 12%. By contrast, China’s share has increased from 2% to 15% between 1990 and 2020, and it is expected to grow up to 24% in 2030, surpassing both South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan. In the same period, the American allotment in global chip manufacturing is expected to decline to 9% if governmental intervention will not be put in place.

This shift is the result of both lower incentives for the U.S. semiconductor sector and tougher measures towards China undertaken under Trump. The Covid-19 pandemic has further aggravated the situation, eventually bringing chips under the spotlight in U.S. government. The high increase in demand for consumer technologies – mainly laptops and smartphones – during the pandemic has led to a critical chips supply shortage in the U.S., leading Biden to sign an executive order that received bipartisan support in Congress in late February. The order authorised the use of $37 billion to foster the American manufacturing of semiconductors, and has furthermore launched a 100-day review on the status of supply chains in four areas that are essential to American competitiveness: semiconductors; key minerals and materials extracted from rare earths; pharmaceuticals; and advanced batteries. The order was signed the day after U.S. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer declared to have directed lawmakers to draft a package of an additional $100 billion as part of a bipartisan bill to implement the NDAA by fostering research and investment in U.S. manufacturing in key high tech areas – not only semiconductors but also Artificial Intelligence and quantum computing - in order “to out-compete China and create new American jobs”.

The crucial passage to rebalance the geopolitics of semiconductors and strengthen American technological competitiveness face to China, thus, lies in American domestic politics. The review launched with Biden’s signature of the executive order is aimed at diversifying and fortifying supply chains, and the SIA insisted particularly upon increasing American chips manufacturing through the mobilisation of federal incentives. About 44% of U.S.- headquartered firms are located in the United States, but the cost to build and operate a front-end fabrication facility (fab) in the U.S. is 25% - 50% more expensive than in other alternative locations. Singapore, for instance, which hosts the majority of U.S. chips fabs based abroad (17%), has introduced hiring credits and a reduced tax rate in the semiconductors manufacturing sector, while American incentives of this kind are almost non-existent. For this reason, the measures announced by Biden and Congress play a very important role in increasing U.S.-made chips and thus fortifying American leadership in the sector by avoiding a shortfall of the U.S. share in the global chip manufacturing at a time when China’s will surely increase as a result of the plan to reach the self-sufficiency in semiconductors outlined in China’s 14th Five Year Plan.

This turn in the American semiconductor policy, however, should not be analysed through a ‘new Cold War’ lens, as China is not only the biggest U.S. competitor in chips manufacturing, but it is also a top costumer of the U.S. semiconductor industry. According to a report from the Boston Consulting Group, prohibiting U.S. chips sales to China could cause the loss of around $80 billion to the U.S. semiconductor industry, compromising the U.S. long-standing leadership position with a loss of about 18% in the American global market share of microchips. For the U.S., the solution to face the challenges posed by China on the high-tech side is found not only in a tougher policy towards Beijing, but in the U.S. semiconductor policy, which will in turn have important side effects on U.S.-China policy. As the Biden administration is likely to adopt a tough but multilateral approach to China – not only on technology but also on a variety of transnational challenges – the oculate application of the resources recently announced by the U.S. government on chips manufacturing can be pivotal both to the maintenance of the U.S. power status and to the re-definition of great power competition.

Martina is a PhD Candidate at the Department of War Studies at King’s College London. She has been awarded the Leverhulme Scholarship “Interrogating Visions of a Post-Western World: Interdisciplinary and Interregional Perspectives on the Future in a Changing International Order”. Her research focuses on the history of U.S. foreign policy towards China, particularly on the role of China in U.S. President George H.W. Bush’s Grand Strategy for a post-Cold War World Order.

She is an alumna of the School of Politics founded by former Italian Prime Minister Enrico Letta, and she holds a first-class honors Master’s degree in International Studies from Roma Tre University, where she also completed her BA in Political Science and International Relations. Throughout her studies, she won different grants to study and do research at the University of Montpellier, the University of Copenhagen, and the University of Montréal, which awarded her with an additional scholarship of the Confucius Institute in Québec to complete a teaching-and-study experience in China.

She is a Senior Editor at Strife.