Mediation of Holocaust Memory Through Diaries

Unlike the Holocaust memoirs that are written ex post facto with an intended audience in mind, the Holocaust diaries, considered as the most intimate and personalized form of literature, are written simultaneously along with the occurrence of historical events in real time. Instead of producing a refined memory of the experience, diaries present a raw memory of the reality of experience. Differentiating between Holocaust memoirs and diaries, Professor James Young in his article, “Interpreting Literary Testimony: A Preface to Rereading Holocaust Diaries and Memoirs” explains that while the former deals with an “analysis of history”, the latter is a record of a “movement of history” (410). As the diarists “wrote from within the whirlwind”, they can be considered to as “far more convincing of their factual veracity than more retrospective accounts” (414).

Unfortunately, as the adolescent diarists are neither in a position to challenge the notion nor to reflect on it later, hence their writings divulge a confused state of mind in which they are trapped. According to Dr. David Patterson, the Holocaust diarists write along the “edge of annihilation, between the collapse and recovery of life” (The Encyclopedia of Holocaust Literature, xvi). The Holocaust diaries are “a flight to the world from the anti-world, a flight to life from the kingdom of death” (xvi). Considering Holocaust diaries as a means of resistance, Dr. Patterson states, “The diarist who maintains an account of the ordeal does so in a realm where keeping such accounts is a capital crime” (xvi). Thus, the Holocaust diaries reveal an interrogation of God accompanied by an underlying theme of frustration, as the young adolescents are at a loss to reconcile the benevolence of God with the daily atrocities they witness and record in their diary.

The Psychic Shift/s

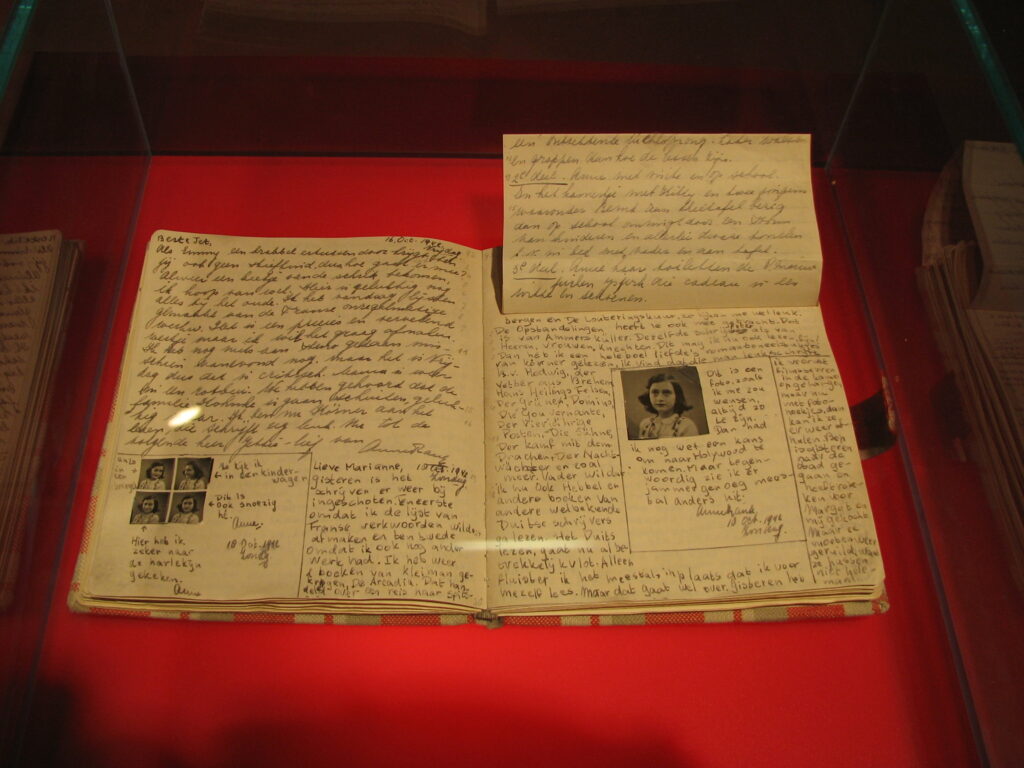

The Diary of a Young Girl is written by Annelies Marie Frank, a German-Dutch adolescent diarist, who chronicled her stay for two years and two months while hiding in the secret annexe within the building of 263 Prinsengracht in Amsterdam. Anne Frank’s diary remains the only existing Holocaust diary that is written in hiding till present. Unlike the ghetto diarists, Anne Frank does not have access to the outside world. Radio broadcasts and helpers of the Frank family are the only connecting links between the outside world and the secret annexe. Regarding her diary as her best friend, Anne confides in it her deepest thoughts and desires. Apart from chronicling the hearsay horrors of the Holocaust, Anne’s diary comprises of witty humour, intolerable tension, adolescent love aches and disillusionments, a growing awareness of sexuality and simultaneous snippets of fear, unrest and joy.

Anne’s adolescent effervescence is cut short, as the Frank family had to move into hiding. The trigger for it was Margot’s “call up” (19) notice that required her to report to the German authorities. As they start their packing, the first thing that Anne packs is her diary. She voices her thoughts and says, “memories mean more to me than dresses” (20). On 8 July 1942, members of the Frank family go into hiding. Their hiding place is located in the building of Otto Frank’s office. This physical shift from their house to the secret annexe in the office building of 263 Prinsengracht is also accompanied by a psychic shift that is apparent throughout Anne’s diary. Cut off from the rest of the world, the circumscribed world of the annexe is interrupted only by the visits of helpers who not only serve as the sources of information but also provide a relaxing respite for Anne. These helpers are the people employed in Otto Frank’s office and include, Mr. Kugler, Mr. Kleiman, Miep and Jan Gies and Mr. Voskuijl and her daughter Bep (Elizabeth Voskuijl), who worked as a typist. In order to familiarize herself with this sudden spatial shift, Anne describes the architecture of the annexe and along with her father unpacks their stuff and sets up the annexe. It is through her diary writing that Anne is able to confront the reality of their hiding.

Soon after, Anne begins to realize her drift from her mother and sister. She says:

I don’t fit in with them, and I’ve felt that clearly in the last few weeks. They’re so sentimental together, but I’d rather be sentimental on my own. They’re always saying how nice it is with the four of us, and that we get along so well, without giving a moment’s thought to the fact that I don’t feel that way (29).

Anne’s feeling of revulsion towards her mother and sister can be explained by secondary individuation process as described by Peter Blos.

The ‘secondary individuation’ process described by Peter Blos in turn is an expanded version of ‘separation- individuation’ process defined by Margaret Mahler. According to Mahler, there exists an incoherency between the physical and psychological development of an individual. She classifies the developmental process into three phases comprising of the normal autistic phase, the normal symbiotic phase and the phase of individuation-separation in which the psychological birth takes place and the child takes his first independent step. These developmental phases mark a transition from a dependent mother-child symbiotic interaction (separation) to the independent state of an individual (individuation) having a sense of self-awareness and identity that is achieved by the third year. These processes of separation and individuation though occur at a different time, are complimentary to each other. Peter Blos expanded on Mahler’s notions and suggested that this early process of separation-individuation acts as a precursor to a later adolescent process, which he termed the ‘secondary individuation’ process. According to Blos, the first ‘separation-individuation’ process helps to create a sense of existence, whereas the second ‘separation-individuation’ process helps to achieve a sense of identity. It is achieved through a psychic restructuring that is helpful in formation of an adolescent sense of self that has a considerable affect on the personality.

Anne detests it when her mother treats her “like a baby” and always finds herself having an “opposite view” than her mother (32). Anne is thus often at conflict with her mother and is unable to reconcile her feelings of love and animosity towards her. Anne reveals to her father that she loves him more than her mother. She further says:

I simply can’t stand Mother and I have to force myself not to snap at her all the time, and to stay calm, when I’d rather slap her across the face. I can imagine Mother dying but Daddy’s death seems inconceivable (51).

Anne’s search for an independent identity is further triggered when a dentist named Dr. Dussel (Fritz Pfeffer) joins the seven hiding members in the annexe. Dussel’s arrival marks a further invasion in Anne’s adolescent world. Prior to his arrival Anne shared a room with Margot. Now she was left with no option but to share her room with him, much to her chagrin. Anne finds him annoying as he “switches on the light at the crack of dawn to exercise for ten minutes” (78) and then begins dressing, which makes the chairs jiggle on which Anne sleeps. Anne continues to face a paucity of space in her room as Dussel refuses to let her use the study table. When she requests him to allow her to use it for two afternoons a week, he agrees but only after calling her “shamefully self-centred” (109). When she suffers from a bad flu, she highly disapproves of Dussel, who offers to examine her. She says, “the worst part was when Mr. Dussel decided to play doctor and lay his pomaded head on my bare chest to listen to sounds” (151). Anne and Dussel, though equally sharing the responsibility of hiding, have an unequal power in using the room space. Thus, in a way Dussel intrudes not only her physical space but her bodily space as well, leaving Anne with no choice but to limit her anger only to the secretive space of her diary.

Conclusion

The psychic shift/drift inevitably becomes an essential part of Anne’s adolescent identity formation. With a growing sense of maturity Anne considers to forgive her mother and sister and also have a fresh outlook towards the van Daan family. She wants to form her own ideals as an independent person. Upon retrospection, she finds the Anne of 1942 with the present Anne, she finds herself wiser and more real than her previous superficial version. Though she has no issues in being indifferent to her mother, but not being able to confide in her father, affects her the most. The adolescent Anne is forced to trust only herself. Thus, Anne’s diary by being both a passive observer and a preserver of her thoughts not only satisfies her need for an emotional dependency but also invariably satiates her need for an identity.

Mehak Burza is currently one of the Board of Directors and the Head of Global Holocaust and Religious Studies at The Global Center for Religious Research (Denver, United States). She is also a Doctoral Holocaust Researcher at the Department of English, Jamia University (New Delhi, India) and has submitted her thesis entitled, Literary Representations of The Holocaust; An Assessment.

Her primary interests include Holocaust/Genocide Studies, Jewish Studies, Gender, Identity, Trauma Studies and PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder).

She has presented her research papers at the Ackerman Center for Holocaust Studies in The University of Texas at Dallas and at the Gettysburg College in Pennsylvania. Her research paper and book reviews have been published in Contemporary Literary Review India. Her translations have been published in Purple Ink, the online journal of Brown University, Los Angeles. On the creative front, her short story and several poems have been published in Visual Verse and Trouvaille Review.