Most studies of conflict focus on interstate rather than global threats. With their theoretical foundations rooted in issues of power, material resources, and territory as held and contested by state actors, rather than addressing disputes that have global effects. The concept of global threats, which here considers all threats that exist beyond the nation-state system in a way that can potentially threaten each individual state, are often pushed to the side or blamed on interstate dynamics. However, global threats from the cosmos can fundamentally change or destroy life as we know it. There are a wide range of space-based threats that can change life on Earth from solar flares to near-Earth objects. While most of these threats cannot be effectively mitigated, near-Earth objects (NEOs), in theory, can be prevented from causing mass damage to life on Earth. To effectively deal with NEOs, and planetary defence, there is a need to establish a new level of international trust and cooperation that will enable humanity to respond to species level threats.

What are NEOs?

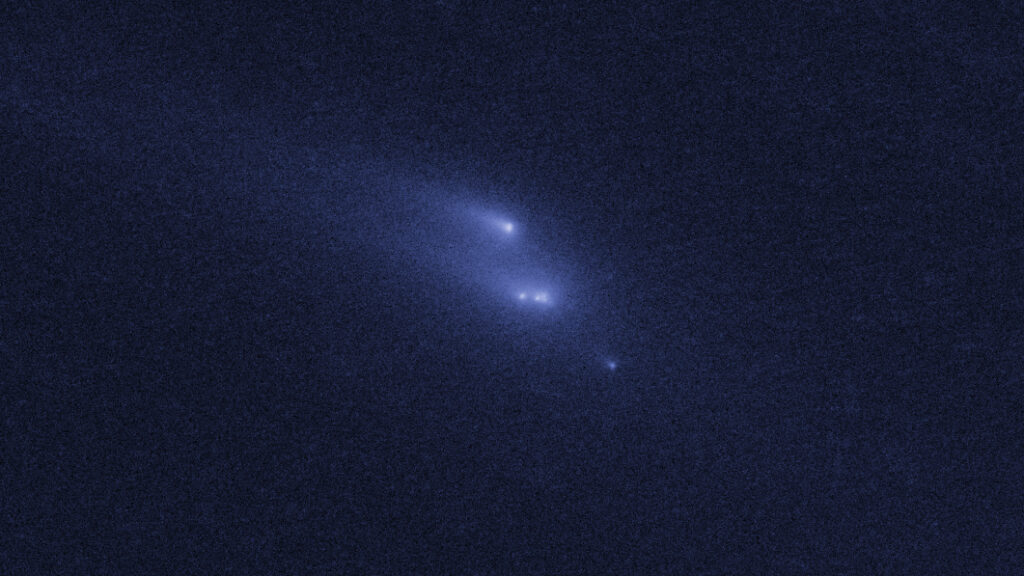

NEOs are comets and asteroids that pass near the orbit of the Earth after being nudged by other celestial bodies’ gravitational forces. Comets and asteroids present a different level of threat to Earth due to their composition. To explain, comets are primarily composed of ice and therefore tend to break in contact with the atmosphere, presenting little to no threat of substantial ground impact. On the other hand, asteroids represent a real threat to terrestrial life, meaning human, animal, and planet life, on Earth because they are composed of rocks and metals. These components represent more of a threat because unlike the ice-based comets, the components of asteroids are unlikely to be fully destroyed upon entry into Earth’s atmosphere. The surviving materials that made up the asteroid can cause substantial impact damage, creating a significant threat.

Existing Mitigation Plans for NEOs?

Dealing with potentially threatening NEOs has become a significant concern for governments internationally. Many organisations around the globe focus on identifying and tracking potentially hazardous asteroids (PHAs) so that humanity has forewarned these threats. However, most acknowledge that they have yet to identify many of these potentially hazardous celestial bodies.

As of now, there are three main options for NEO threat mitigation. The first is blast deflection. A blast deflection is an attempt to change an asteroid’s orbital path by detonating a large explosive device, typically nuclear, near the asteroid, applying pressure without shattering it. Another mitigation is a theoretical device called a gravity tractor. A gravity tractor is a device capable of creating enough gravitational force such that it can pull and change the path of an asteroid, thus preventing collision with Earth. As of now, no such device exists.

The third method for dealing with NEOs is a kinetic impactor. This uses kinetic force to hit or ram against an asteroid, changing its course. The main difference between kinetic impactors and blast deflections is that the impactor is not designed to break apart an asteroid. Rather, a kinetic impact is designed just to use enough force to change the path of an asteroid.

Of these three possible methods of dealing with asteroid threats, kinetic impactors are the only ones with a plan to be tested. NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), a kinetic impactor test, is targeting the binary asteroid, Didymos as a test subject for the principled effectiveness of kinetic impactor mitigation techniques. Ideally, the force from the rocket impacting Didymos’ small moonlet will have enough speed and force to change the orbital period of the moonlet. If successful, this test will show that kinetic impactor methods of dealing with NEOs can effectively deal with possible future threats without the possibility of any impact on Earth or entrance into the atmosphere.

Why More International Cooperation Matters

When dealing with global threats, it is difficult to imagine any resolution without a significant level of international cooperation. Indeed, we have seen this before across other space-related problems. For example, there is cooperation in defining the lawful actions in space with the Outer Space Treaty. There is also cooperation in science with the development and continued use of the International Space Station (ISS) which has five different space agencies and 15 different countries involved in the projects onboard.

NEOs and practices to reduce their potential threats to Earth require new levels of trust and cooperation. This new level of cooperation is essential, especially when considering the methods in which NEO threats would be mitigated. For example, blast impactors argue for introducing nuclear weapons in space. According to the Outer Space Treaty, no nuclear weapon or other weapons of mass destruction should be placed in or around the orbit of a celestial body, nor should such weapons be stationed in outer space. Using nuclear weapons in space to deal with NEOs, either from an Earth launch or a space-based launch, would open justifications space-station nuclear weapons for general state security. In this sense, nuclear weapons could be dual use, meaning they can be stationed for planetary defence or used against adversaries. The same could be said for kinetic impactor systems.

Asteroids also present a secondary risk. If impacted in certain ways, they can break apart, shifting the threat picture from one large NEO to multiple smaller pieces. These smaller pieces can still enter the atmosphere creating mass destruction on Earth. The 2013 Chelyabinsk meteor helps illuminate the potential risk of even smaller asteroid piece impacts. The Chelyabinsk meteor created an air blast more than 15 times greater than the blast created from the nuclear bomb, Fat Man, dropped on Nagasaki, with each blast equivalent to 300,000 and 20,000 tons of TNT, respectively. Unlike Nagasaki, most of the damage was property damage, damaging around 7,000 buildings and injuring just over 1,600 people.

In theory, the timing of breaking up an asteroid on its course to Earth could also limit the damage done to only specific regions of the world. Therefore, if the destruction of an asteroid is timed correctly, the smaller pieces may not constitute a global threat but could still be used to decimate an adversary or an entire region. With this secondary level of risk at play when dealing with NEO threats, there must be a level of international cooperation to ensure that steps would be taken to avoid this type of targeted destruction. Failure to do this could lead to miscommunication about rocket launches, either with Earth-saving missions or launches more sinister in nature.

To deal with such global threats, humans need to overcome traditional notions of international security and conflict discussions. Establishing regulatory regimes to manage the activities of private and governmental corporations, along with establishing legal parameters around the appropriate uses of potentially dual-use technologies, is essential for any planetary defence measures. Such regulatory and legal parameters could include outlining differences in space-based defence systems that utilise nuclear weapons for only planetary defence purposes. These parameters would also have to revisit and update the Outer Space Treaty to reflect legal limitations on new technologies designed to deal with possible threats from the cosmos.

While NEOs may not be the most pressing threat to humanity now, they do present an avenue to establish broader international cooperation in areas affecting the globe. Lessons learned from cooperation and trust built when researching and defining how to respond to NEOs threats can be translated into addressing other global threats such as climate change, mass hunger, and water shortages. The politics of space do not happen in a vacuum but rather provide space for humanity to learn how to work together better.

Keelin Wolfe

Keelin Wolfe is a MA student from the Department of War Studies pursuing a degree in International Conflict Studies.

Her research areas focus on arms sales and arms control, WMD strategies, and divided armies research. She received her BA from George Mason University in Government and International Politics earning honors in the major and a Summa Cum Laude distinction. During her time at GMU, she was a member of the Honors College and a member of an academic fellowship called the Global Politics Fellowship. She also was a fellow in the Hertog Foundation Summer Fellowships in Nuclear Strategies and World Order.

She is a Staff Writing Fellow at Strife.