by Sonia Martínez Girón

There seems to be some sort of 404 error in cartography. Internet maps plainly show ‘no data’ in Western Sahara. How exactly did this global anomaly to the twenty-first-century nation-state construction occur? Most importantly, can it change? Examining diverse perspectives can help venture into what could ease Western Sahara’s socio-political situation.

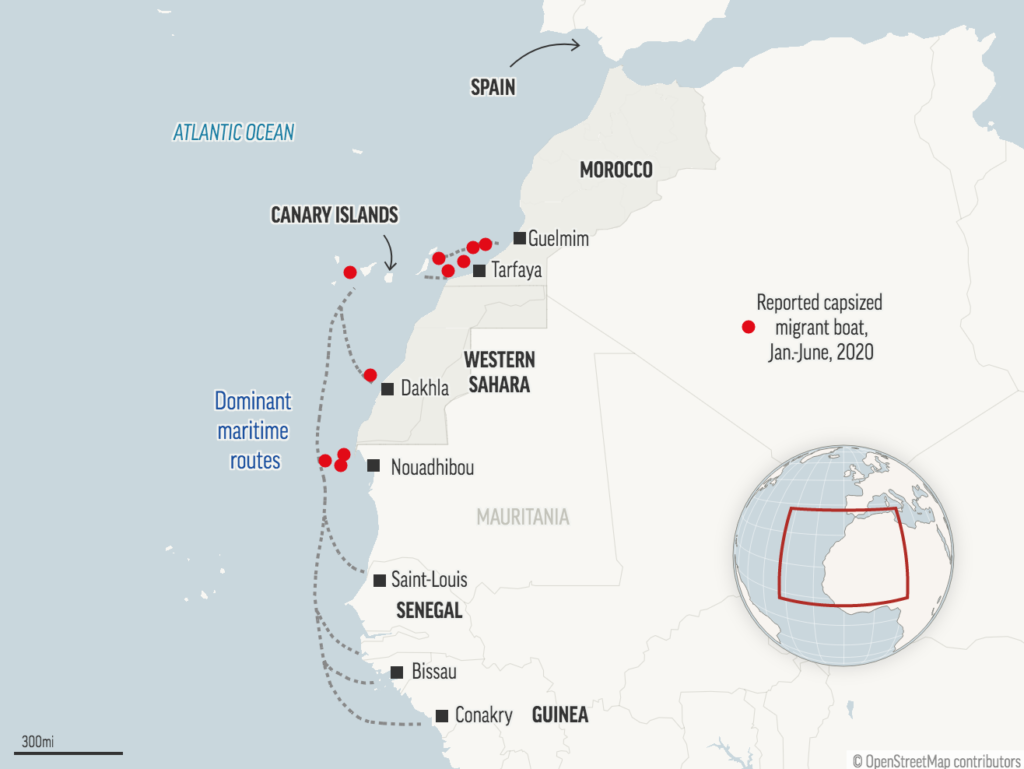

Western Sahara covers a 266,000-sq-km area within the Sahara Desert on the Atlantic coast of Northwest Africa. In this territory, the sovereignty of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) has not been internationally recognised. This is an intricate conflict where numerous parties and identities are involved. Morocco has just initiated military operations in the area, raising tensions within the ‘stable instability’ that characterises the territory and disrupting the brittle ceasefire of the last three decades. The Polisario Front, the pro-independence unit supported by Algeria, is based in Tindouf since 1975. The position of the Polisario is that the irresolution of the Security Council has given it no alternative than to “escalate its fight”, as the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) has been ineffective in preventing confrontations. Despite this state of affairs, the UN has accorded to extend the United Nations mission until 31 October 2021. Historical context can help appreciate the big picture.

To begin, the ‘Spanish Sahara’ was what the Territory of Western Sahara was called between 1884 and 1976, while it was occupied by Spain. It was within the context of the Berlin Conference of 1885 where Spain was permitted to occupy the region over which the country could make historical claims. In 1975, Spain withdrew from the colony. Spain was undergoing a period of instability, in which profound divisions and internal conflict marked by the end of Francisco Franco’s dictatorship. The United Nations (UN) mission had intervened in the territory in response to the Morocco-Mauritania campaign to prevent the self-determination vote that the Spanish government had professed in 1974.

In November of 1975, Hassan II of Morocco took advantage of the circumstances to organise the Green March, a protest aiming to annex the Spanish Sahara to Morocco where troops of volunteers crossed to the Spanish Sahara. Arias Navarro, the Spanish president at the time, ordered the colony to be withdrawn and abandoned. That same year, just days before Franco died, Morocco, Mauritania and Spain signed the Madrid Pact to formally end the Spanish occupancy of the Western Sahara territory, which stated that the decolonisation of the region and the opinions of the Saharan population would be respected. While the treaty came into force, its international recognition was not expressed. After the Spanish withdrew from the territory in the 1970s, Western Sahara was annexed by Morocco and Mauritania in 1976. In 1979, Mauritania renounced ‘its share’ of this land and Morocco constructed a 2,700-kilometre wall with landmines alongside that has retained the Polisario. Since then, Western Sahara has been a territory administered de facto by Morocco.

In September 1991 and after 16 years of war, a truce was signed by the parties of the conflict. Still, the intended plebiscite of auto-determination for Western Sahara has been recurrently suspended, as there seems to be no consensus between Rabat and the Polisario Front – who the UN considers to be the legitimate representative of the Sahrawi people – over the conformation of the electorate and the status of the zone. A political settlement in Western Sahara has been even more difficult after Morocco intervened last month. According to Morocco, the country had merely erected a “security cordon”.

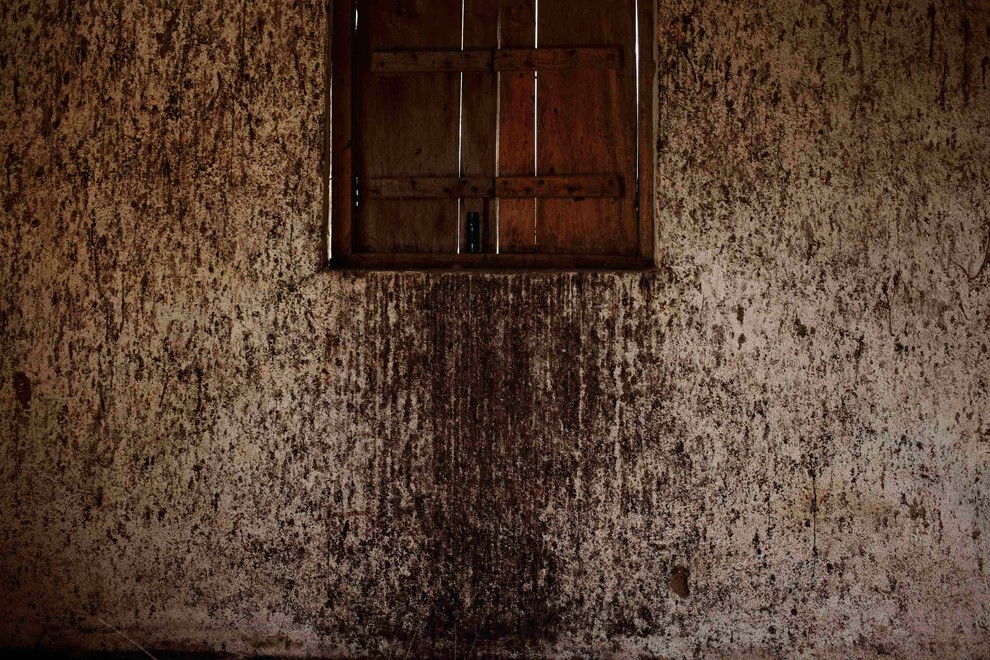

The Polisario Front considered the truce with Morocco to be over after Morocco’s attacks. Bachir Sayed, the Polisario Front leader, stated that the 13th of November was a turning point in the Saharawi national struggle and stressed how Sahrawi people support the Polisario Front. On that day, Moroccan soldiers had shot at civilians who had been protesting against what they consider to be Morocco’s exploitation of reserves. Sayed suggested that the war of national liberation was caused by Morocco’s violation of the ceasefire and the UN’s indifference. Since last month, the UN has multiplied its efforts to prevent further escalation in the Buffer Strip in the Guerguerat area. Morocco’s position on the sovereignty of the Guerguerat area is that it is a ‘no man’s land’; while the Front considers it its ground, appealing to the agreement signed by all parties in 1991. This back-and-forth between both sides is a continuation of previous themes of the territorial dispute. During these decades, the UN has been trying to balance the possible applications of sovereignty and self-determination. Stéphane Dujarric, Spokesperson of the UN, alleged that both Morocco and the Polisario should show some responsibility. Regarding how this unsolved dispute has affected the Sahrawi population, Amnesty International highlights that human rights abuses have been committed in the disputed territory over the last 40 years.

The Sahrawi population has waited for a legal referendum that has not yet arrived. Although this ceasefire was thought to entail peace, the absence of active conflict does not mean that the dispute has settled. The promise of a referendum remains crucial, especially for the many exiled Sahrawis involuntarily living in camps near Tindouf. Still, there seems to be no consensus regarding the census for a referendum for the West Sahara natives. Adding fuel to the fire, President Trump newly recognised Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara via Twitter as compensation for the normalisation of Morocco-Israel relations. While this can account for the existing trade relations between Rabat and Washington, Trump’s announcement shows little engagement with the conflict itself and the pleas of the Sahrawi’s.

In the future, the international community will continue to observe how Western Sahara events unfold, most likely with significant concern. Ironically enough, the etymology of the word ‘referendum’ means ‘that must be brought back or taken back’. Concerning the Sahrawi community, maybe the word choice of ‘election’ would be more accurate, as one cannot have back what one never had. In this sense, it is consistent to state that those who were part of the problem should be part of the solution. The UN should embrace a new approach, as this strategy has not proved efficient for the last decades. If the Sahrawi people had the choice of independence or incorporation to Morocco, this setting would feasibly alter.

Sonia is an MA International Affairs student at KCL. She holds a Bachelor in Modern Languages from Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. In her Bachelor thesis she explored the use of language in the context of the Spanish Civil War. She is a gastronomy enthusiast. Sonia follows International Security issues with particular interest.