by Mariana Vieira

The transition from British to American hegemony, a shift that fundamentally shaped the post-1945 world order, is often characterised as peaceful. This is brought about by the choice of terminology and the analytical slippage between hegemony and empire. While there were no direct hostilities between the UK and the US as the former declined and the latter ascended, the study of empire highlights the conflict and violence of the two key processes of transition: the rise of the United States and the decline of Great Britain. Indeed, terminology matters because it enables scholars to consider the interactions and dynamics between metropole, the core territory around which power is centralised, and the extensive periphery of dominated areas.

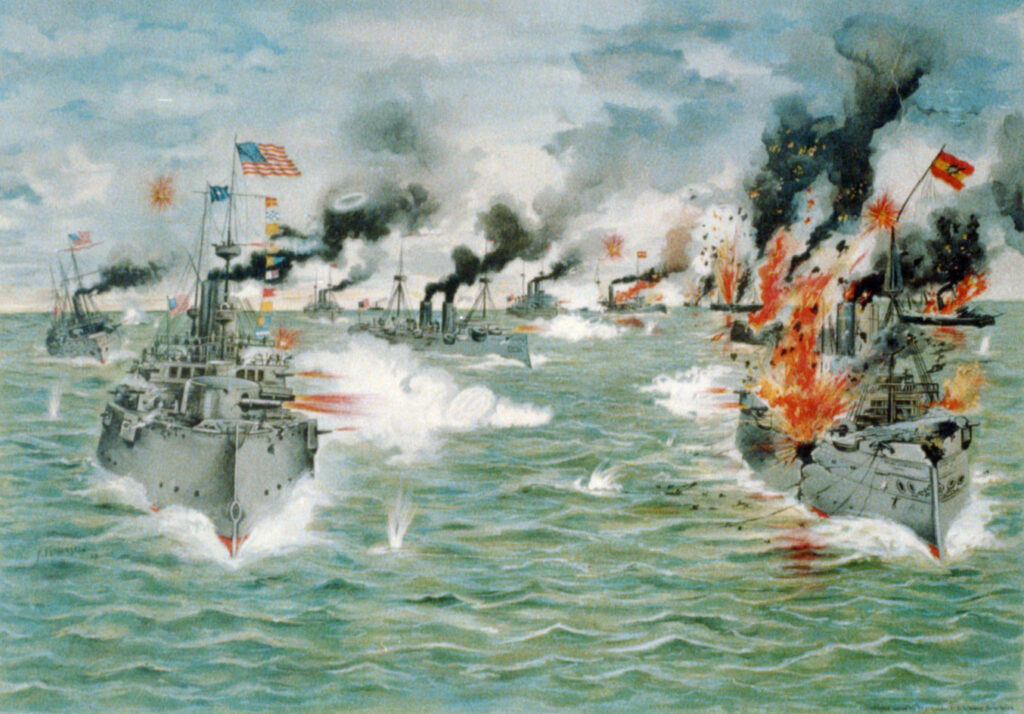

The transition from Pax Britannica to Pax Americana did not happen immediately and the building blocks leading to it were hardly peaceful. Special mentions include the Spanish-American War (1898), the wars of decolonisation, and both World Wars. The absence of a typical hegemonic war between the dominant power and the rising challenger led experts to believe that a peaceful transition took place sometime in the early-mid twentieth century.

However, in determining a more precise timestamp, the most persuasive dates do follow a conflict that fits with the other main characteristics of hegemonic war: a total conflict involving major states that is unlimited in terms of political, economic, and ideological significance. Here, the Second World War epitomises the decay of the European international political order and the triumph of American power. Moreover, even proponents of the peaceful transition thesis highlight how the US became committed to enforcing order internationally after the ‘cataclysm’ of the Second World War.

US hegemonic ascendency accelerated after the annexation of overseas territories, the spoils of the American victory in the war of 1898. While these territorial acquisitions were unprecedented, the Spanish-American War and its consequences have been argued to represent a ‘logical culmination’ of the major trends in nineteenth-century US foreign policy. In removing Spain from the Western Hemisphere and increasing American’s reach in East Asia, the war was crucial in advancing the US’ status as a world power and a full-fledged member of the imperial club.

Analysing America’s colonial experience during the earlier period of transition as an empire, as opposed to as a hegemon allows for a more complex image that highlights the violence and day-to-day coercion intrinsic to how the American empire was built. Whereas hegemons are strictly concerned with influence over foreign affairs, empires seek to exert control over the political regime of the periphery, thereby encompassing both domestic and foreign policy spheres. As an empire, the US proceeded to transform Cuba into a neo-colonial economy built around cash-crops and closely tied to the US market, while the Philippines witnessed an especially brutal war of ‘benevolent assimilation’ furthered by ideologies of racial difference.

The following period of US hegemonic maturity and UK hegemonic decline was partly engendered by significant changes in the international context. As the US entered a global field that was already mostly colonized, it seemingly maintained international peace – or the existing level of colonial violence – by supporting its European allies and outsourcing territorial control. However, the emergence and proliferation of anticolonial nationalism in the periphery changed the global landscape. As the First World War brought to a boil the decades long-simmering tensions of militarism, alliances, imperialism, and nationalism, its aftermath witnessed the break-up of several empires on the losing side, the weakening of the victorious’ hold on their colonial possessions, and the widespread circulation of President Wilson’s Fourteen Points.

The diffusion of ideas of national self-determination in European colonies resulted in multiple movements against colonial rule, including in Britain. Crucially, the rise of nationalism and the eruption of conflict furthered the British hegemonic decline. The transition from British to American international systems was consolidating as the USA found other means to exert their – informal – influence, while the British could not meet their economic goals without the colonial – formal – dimension.

Partly distracted with crises in the Middle East, East Asia, and South Africa and partly constrained by the importance of American raw materials and markets, the British did not seek to actively oppose America’s rise in the Western Hemisphere. Arguably, if there was a shift from perceptions of competition to cooperation with the US, it was largely a result of British non-peaceful priorities laying elsewhere. The British operated a trading empire based on the exchange of European manufactured goods for the colonies’ foods and minerals, relying on imperialism to maintain its economic supremacy.

However, as empires became increasingly illegitimate, the cumulative effect of peripheral wars of decolonisation and the deterioration of the British industrial base undermined the productivity on which its power hinged. In the metropole, the devastating impact of the two World Wars added a further dimension of resource erosion, this disrupted the imperialist center and left the British Empire dependent on American economic and military power. Consequently, the British hegemonic decline was accelerated by interacting conflicts in the center and in the periphery.

It was not a white dove that brought about a new imperial center, but rather a murder of crows.

Finally, when contending the emergence of a ‘peaceful’ international order based on the convergence of Anglo-Saxon values, a study of empire may point in other directions. Both empires share similarities, as capitalist nation-states with an impulse to act imperialistically in ordering their respective international systems. The US gunboat diplomacy showcased its contempt for ‘lesser’ peoples, thereby placing America in the mainstream of Western imperialism. Here, the American elite followed the debates on empire in Britain, applying notions of racism and the white man’s burden to US expansionist imperatives. In hailing the intellectual, industrial, and moral superiority of the Anglo-Saxon peoples, the sense of sameness legitimised and fueled more violence towards ‘backward’ people and ‘little brown brothers’ in the periphery during the initial phase of transition.

For centuries, the rise and decline of powerful empires characterised world politics and not the world of nation-states that is taken for granted in International Relations (IR). The perception of a peaceful hegemonic transition is based on the Westphalian terms of reference, but the framework of sovereign states occludes and distorts imperial relations.

Careful consideration of British decline and American rise showcases precisely these two antonyms of peace: war, on a global scale, and conflict, within their respective peripheries. In rendering the violence of the processes behind this ‘peaceful’ transition visible, the study of empire warns against Eurocentric celebrations of a successful model that rising – non-Western – powers should follow. It was not a white dove that brought about a new imperial center, but rather a murder of crows.