by Carlotta Rinaudo

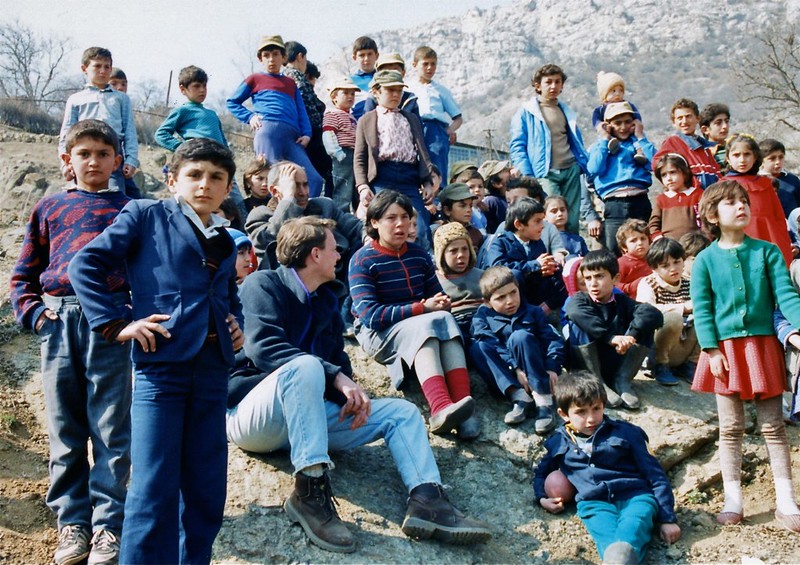

In 1988 the kids of Nagorno Karabakh did not attend school. Instead of books, they took stones, sticks and knives and waited in the streets to attack Azerbaijani’s cars. Such inter-ethnic hostility can be traced back to an ill-fated decision taken by Stalin in 1923, when Nagorno Karabakh was made an autonomous region under Soviet Azerbaijan, despite being inhabited by a 94% ethnic Armenian majority.

In the late 1980s, as the Soviet Union collapsed, ethnic Armenians called for the transfer of Nagorno Karabakh to the jurisdiction of the Republic of Armenia, spurring violent reactions from resident Azerbaijanis. Tensions led to the 1988-1994 war, with both sides engaging in ethnic cleansing. In the end, Armenia took de facto control of Nagorno Karabakh and the surrounding seven districts, resulting in the displacement of 600,000 Azerbaijanis.

“The Azerbaijanis wanted to kick us out of Nagorno-Karabakh, but we started to fight back and threw stones”, recalls Aram, then only 14-years of age.

Today, this landlocked mountainous region in the South Caucasus continues to be engulfed by violence. On 27 September 2020 conflict broke out again, and after six weeks of intense fighting a peace deal was signed on 9 November. This time, the conflict translated into a painful defeat for Armenia and a victory for Azerbaijan, while also determining a shift in regional power dynamics: Turkey has strengthened its position in the region, constraining Russia to a secondary role. This raises new questions: what are the implications of a new balance between Ankara and Moscow in the South Caucasus? Also, as Azeri refugees and Armenian separatists will cohabit again, how likely is more ethnic cleansing?

Many factors suggest that this long-lasting conflict is far from being resolved.

Nagorno Karabakh is not the only territorial dispute that has emerged from the ashes of a disintegrating Soviet Union: other non-recognised states are Abkhazia and South Ossetia in Georgia, Transnistria in Moldova, and Donetsk and Luhansk in Ukraine.

These are categorised as frozen conflicts because of their unresolved nature; within these regions, clashes could re-start at any time. Frozen conflicts can also transform into a boxing ring where international players can flex their muscles and push their aspirations. Thus, after backing opposite sides in the ongoing conflicts in Syria and Libya, in September Russia and Turkey extended their regional competition to Nagorno Karabakh.

Azerbaijan – Turkey

On one side of the ring stand two fighters: Azerbaijan and Turkey, bound by historical, cultural, and ethnic ties. Their alliance, however, goes well beyond brotherly love, indeed, their cooperation benefits both their national interests.

Over recent years, the Azerbaijani government has grown increasingly frustrated at Armenia’s behaviour, especially when Yerevan rejected the Madrid Principles, which entailed the restitution of the seven districts surrounding Nagorno Karabakh. Thus, by starting a military operation on 27 September 2020, Azerbaijan aimed to re-gain by force the territories it had lost during the 1988-1994 war. Back then, its military power was inferior to Russian-backed Armenia, but today things have changed, Azerbaijan’s rising oil revenues have opened the possibility of a heavy rearmament. Turkish military exports to Baku increased six-fold this year, with Ankara sending drones, aerial support, and even Syrian mercenaries. Thanks to its petrodollars, Azerbaijan has been provided with a decisive military power it did not have in 1994.

Meanwhile, Turkish President Erdogan aims to restore the grandeur of the Ottoman empire. After engaging in a number of disputes throughout the Middle East and the Mediterranean, Ankara has now seen a chance to stretch its neo-Ottoman ambitions to the South Caucasus.

But the conflict is also about securing the energy flow, another sphere where Azerbaijani and Turkish interests converge.

As Nagorno Karabakh sits close to vital Azeri oil and gas infrastructure, long-term disruptions in the region would impact Azerbaijan’s exports towards Southern Europe, but also Turkey’s cheap gas imports, allowing a Russian victory in the European market.

Armenia - Russia

On the other side of the boxing ring are Armenia and Russia, whose historical alliance has recently become more fragile.

On paper they both are signatories of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation, a military agreement of mutual defence. However, Moscow did not intervene to protect Armenia during the recent six-week conflict, supposedly in order to avoid a direct confrontation against heavily-armed Azerbaijan. In addition, over the past years Moscow and Baku enjoyed good relationships. Thus, Moscow might be unwilling to break ties with a friendly ex-Soviet state that is even an arms customer, altering the fragile equilibrium of its “Near Abroad”.

On the other side, Putin seems to have some reasons to be less eager to help Yerevan. The new Armenian government came into power in 2018 following a colour revolution, notably one of Putin’s worst nightmares. The government in Yerevan is also prosecuting former President Kocharyan, who used to enjoy a friendly relationship with the Kremlin. In addition, Yerevan is welcoming Western NGOs, while its media wrote many critical publications about Moscow.

What’s next?

As Shusha was captured by Azerbaijani forces on 9 November 2020, Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan rushed to sign a late-night peace deal with Russia and Azerbaijan, fearing that more territory could be lost. Perched atop a mountain overlooking Nagorno Karabakh’s capital, Stepanakert, Shusha represents a strategic gain, but it also carries historical meaning for both Armenians and Azerbaijanis, often referred to as “the Jerusalem of Nagorno Karabakh”.

According to the peace deal, Baku will assume official control over its recent territorial gains, and Azeri refugees will now be able to return to their lost lands. In addition, Armenia must agree to a transport corridor that will link Azerbaijan with its Nakhchivan exclave, so far separated from the mainland.

The peace deal forges new power dynamics: behind the veil of a successful Russian mediation, Moscow’s influence in its own backyard has decreased.

Although nearly 2000 Russian peacekeepers from the 31st Independent Guards Air Assault Brigade have been deployed to monitor the implementation of the ceasefire, Turkish peacekeepers will be dispatched too, cementing Turkish newly acquired key role in the geopolitics of the Caucasus. The increasing Turkish prestige is also demonstrated by the fact that the Russian ally was defeated, while the Turkish ally won.

In conclusion, the prospect of Azeri refugees and Armenian separatists living side by side generates new concerns.

On the one hand, displaced Azerbaijanis carry feelings of resentment against Armenians. Whilst on the other, Armenians often argue their identity was threatened by Turkic peoples; having faced disproportionately higher taxes under Ottoman rule and experiencing mass killing by Ottoman Turks between 1914 and 1923.

Therefore, the recent peace deal is likely to re-open old historical wounds.