By Strife

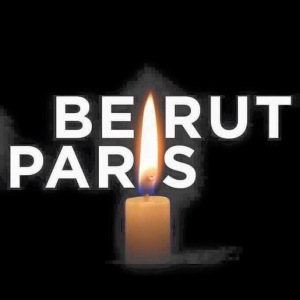

On November 13, three teams linked to ISIS carried out seven seemingly coordinated attacks across Paris, killing 139 people and bringing the city to its knees. Sadly, this was not the only attack this past week. On November 12, 43 people were also killed in a double suicide blast carried out by ISIS in Beirut targeting Shia’s. Also on November 13, ISIS carried out a dual attack targeting Shia’s in Baghdad, killing 26, while several people were killed in a suicide attack targeting a mosque in Shibam, Yemen.

While Paris continues to reel, it also appears to dominate the media and there has been a growing sense that not all victims of terrorism are viewed the same. A rising chorus of voices are asking, ‘what about us?’

Today, Strife talked to recent War Studies graduates Talar Demirdjian and Helene Trehin, who were in Beirut and Paris (respectively) at the time of the attacks to discuss their experience and perceptions of responses to the attacks.

Can you describe where you were and what the situation was like at the time of the attack in Beirut or Paris?

Talar Demirdjian in Beirut: I was at home when the bombings occurred. Ironically, Beirut hadn’t seen a bombing of this sort in a while, so we were stunned at first, and absolutely livid next. It’s one thing when our internal struggles get in the way of our everyday lives (political turmoil, corruption, garbage crisis etc.), it’s another thing when a ruthless insurgent terrorist group brutally murders our innocent people.

Helene Trehin in Paris: Two of my friends and I were in a bar further South West when the first attacks erupted in Central Paris outside the Stade de France and in the 10th district. The football game was being broadcast in the pub but (surprisingly) we didn’t hear immediately about the explosions and shootings and when I left the bar around 21:45, the French and German football teams were still playing, while the first tweets reacting to the attacks started to appear on my phone! Rapidly, more and more channels and people started commenting on this unprecedented episode, and by the time I arrived home the Bataclan attack, first described as a hostage crisis, had begun.

What kind of response to the attack did you observe from your fellow citizens?

Beirut: The anomaly that is Lebanon, is that, we, the people, live a life with a gaping hole in our chest that we cover up with Band-Aids. We’ve been hurt so many times, by so many different entities, that in a way we have become desensitized. We grieve and mourn, get angry, curse this country, curse the Middle East for being so volatile, curse the West for always interfering in the wrong place and the wrong time, and curse the fact that we have to live in a place that offers no safety. Then we become oddly patriotic, praying for all the lives lost, vowing that we’ll make a change, and then we forget and carry on with our lives. It is a vicious cycle that we must commit to, or else we’d lose our minds.

Paris: Everything happened very quickly. I spent hours on my phone calling my friends and on my computer watching the dozens of graphic images and scenes of terror coming out of Facebook and Twitter

For the first 30 minutes, news about the Paris attacks trended as the death toll reached to 128, shortly before midnight. However, rapidly, Parisians living in the targeted places started to use the social media to share messages of support and show their solidarity. On Twitter, the #PorteOuverte (#OpenDoor) hashtag started being used by Parisians to offer shelter and safety to visitors and those stranded. Also, the Facebook safety check enabled us to notify friends and family members that we were unharmed and quickly know loved ones were OK.

What kind of response did you observe from the international community?

Beirut: Another reason for our anger, is the ignorance that we are faced with by the international community, making us feel like second rate citizens, which was emphasized even more by the attacks that occurred in Paris, a day after the Burj al-Barajneh suicide bombings in Beirut. We also mourn the losses that they faced and empathize with them, as we are able to.

However, we’re aggravated by how we are discriminated against by even the simplest of things, like how Facebook’s “Safe Check” didn’t activate for us, or how we don’t get an app to add our Flag on our profile pictures - these small things emphasize how the world does not regard us with as much concern as it does the people of first world countries.

In addition to that, the way the western media portrayed the bombings, as “attacks on a Hezbollah stronghold.” It was as if it were some type of military attack, instead of outright terrorism, when in fact, it was just an attack against innocent civilians at a shopping mall. It proves that to the rest of the world, we are just pawns in game of powers in the Middle East, and our lives have no real value.

Paris: Surprisingly, the first messages I got asking if I was safe were coming from my friends in the United States and Canada. Actually, President Obama was one of the first to comment and condemn the violence. This morning, when I checked Facebook, friends from all over the world had used the hashtag #PrayForParis to show support, some of them even using French words and hashtags such as #JeSuisParis or #NousSommesUnis.

What implications will the attack have on your life and in your community?

Beirut: Sadly, this attack will hardly have any real impact on our community, because attacks have been carried out by other actors so many times before. However, perhaps since this has been a publicly identified attack by ISIS, the Lebanese government might take future precautions, but I won’t get my hopes too high.

In a country where our basic human rights and needs are rarely met, how can we trust our leader to do their most important job, which is keeping the Lebanese people safe? These leaders have illegally extended their own mandate, have not fulfilled their jobs by electing a new a president, instated a proper law for the garbage crisis, or allowed Lebanese women to pass on their nationality to their children.

Paris: “If we are facing in the right direction all we have to do is to keep on walking.” Today, Parisians, fellow French citizens, and the international community are united and showing solidarity in the wake of the disaster. Yes we are shocked by what happened but we cannot be afraid of the future because of an attack and more importantly we must not become a monster while trying to defeat a monster. “Darkness cannot drive out darkness” Martin Luther King Junior said, and when it’s dark we need light. Last January the same kind of terror attacks happened with Charlie Hebdo, but despite the fear of terrorist incidents we stayed together and united. We have to keep on walking.

What kind of distinct pressures have you noticed in your community in relation to these types of attacks?

Beirut: The biggest issues that usually result from these types of attacks are finger pointing and blaming of one party to another for being the perpetrator. However, since ISIS took credit for this attack, the real result might be actual unnerving fear by the Lebanese public, who for now, have been faced with many hardships. Historically though, most bombings were very political and calculated, whereas when dealing with a terrorist group like ISIS, who has known allies in Lebanon in the form of Jebhat al Nusra as well as expansionist ideals, things might actually get messy.

Paris: After the Charlie Hebdo attack last January, I was particularly afraid that it would increase anti-Muslim sentiments but, surprisingly, many reports suggested that those incidents did not contribute to a rise in racism. Today, the situation is different. The economic situation has changed, but the refugees’ crisis and the growing divisions between EU members about the Syrian conflict and ISIS have led the countries to turn inward. As a matter of fact, the French President announced that France would reinstate border controls for several weeks, during COP21.

Terrorism is a phenomenon and its success depends on how a targeted nation will react. Yes, terrorist attacks are politically loaded and emotionally charged but we must not become a monster to defeat a monster.

In your opinion, what positive steps can be taken both domestically and internationally to prevent/respond to such attacks?

Beirut: The unfortunate situation is that the bombing in Paris (not in Beirut), will likely result in Islamophobic rhetoric being spread. This has already started, which will in turn cause a ripple effect into governments who will restart their “crackdown” on the Middle East, likely sending in drones, potentially taking innocent lives, and furthering the notion perpetuated by ISIS that the west is evil and hates the people of Middle East. Such actions give ISIS fuel to spread their ideologies even further, thus a never ending cycle is is born. To contradict that, the international community must find other, more strategic ways to combat organizations like ISIS. Infiltrating and attacking the Middle East has proven, as seen under George W. Bush for example, to be a failure of epic proportions.

Paris: Unfortunately, there is a lot of media misinformation allowing rash judgements about the terrorist identities, for example. As soon as ISIS claimed responsibility for these attacks, anti-Muslim virulent messages started trending on Twitter and Facebook. What we need is to stop using religion for political purposes. People fail to grasp the meaning of words, to understand the purpose of religion, to see the polarization that attends religious issues, and this has overshadowed any nuanced discussion of the matter. “Our faith must go to music, kissing, life, champagne and joy” Johan Sfar happily said!

Talar Demirdjian has recently obtained her Masters degree in Terrorism, Security, & Society from King’s College London, after completing a BA in International affairs & Diplomacy from Notre Dame University-Louaize, and has recently returned to Beirut, Lebanon, her hometown. Her previous work experience include a long stint as a Social Media Manager and copywriter, she was even the former webmaster and editor for Strife. However, she is still in pursuit of finding her role in making the world a better place. You can follow her on Twitter @AcidBurn_TD.

Helene Trehin has recently obtained her Masters degree in Conflict, Security and Development from King’s College London. After completing a BSc. in International Studies at the University of Montreal in Canada, she moved back to France where she worked for the French Ministry of Defence as an analyst. She is currently account manager for The French Polar Cluster, and Coordinator of the Arctic Encounter Paris 2015 Symposium on Arctic Business, Economics and Policy.