By Zach Beecher

Central to understanding the outbreak of violent conflict is the question of what propels the first combatant to pull the trigger and propel the force of his or her voice through the barrel of a gun. Recent literature aims to understand the role of horizontal and vertical inequality in the initiation of war. Yet, despite strong correlations, there is seemingly no smoking gun from the start of conflict indicating a causal relationship with inequality. Ultimately, inequality, whether horizontal or vertical, cannot be said to be “the lone ranger” in triggering conflicts, it is dependent upon a host of interdependent variables that must act in symphony to create the cacophony of war.[1]

Vertical inequality is the measure of “how income or another attribute is distributed among individuals or households in a population.”[2] Typically measured within a particular country though sometimes globally, it ranks the population from top to bottom in terms of distribution of income or a similarly inordinate variable.[3] Examining vertical inequality and what it reflects about a population illuminates the gaps that must be surmounted to provide for improved “social mobility” in the population.[4]

Seeking to break the cycle of violence in a scramble to the top, the dawn of the 21st century marked confidence and ambitious goals in eradicating vertical inequalities. Five years ahead of its own schedule, the World Bank reportedly halved the 1990 worldwide poverty rate of 36% to a mere 18%.[5] Despite this accomplishment, results are uneven throughout the world and the ultimate goal of eradicating “extreme poverty” by 2030 is likely futile.[6] Though these programs focus on sheer numbers rather than specific group dynamics, a more peaceful century should have been at hand.[7]

Figure 1: Millions of Impoverished People and Percentage of Global Poor Over Time[8]

However, Christopher Cramer identifies flaws in the empirical arguments for the causal relationship between vertical inequality and the onset of violence. First, he identifies the problematic definition of what is specified as the onset of violent conflict by evaluating the Gini coefficient.[9] He compares five countries: Brazil, Guinea Bissau, South Africa, and Panama. In Figure 2, one can see South Africa and Guatemala that faced considerable intrastate violence during the period of 1944 to 2000 as opposed to those on the right who did not face significant intrastate violence.[10] Yet, the inequality of the “no conflict” nations are more extreme. Brazil further complicates this when one considers the extraordinary violence in its borders not related to an attempted overthrow of the government.[11] Thus, Cramer holds that inequality may be the seeds of violence, but it may fester and manifest in different ways depending on context.[12]

Figure 2: Gini Coefficients of Nations Suffering Intrastate conflict vs. Nations Not Suffering Intrastate Conflict[13]

Further, Cramer notes the lack of a “linear” relationship between homicide and violence in society to varying degrees of economic inequality.[14] He points out that the more equal nations of Finland, South Korea, and Costa Rica show no significant differences in homicide rates when compared with a significantly less equal country like Venezuela[15] Amartya Sen echoes this argument by pointedly noting that Kolkata, India is simultaneously one of the poorest cities in the world as well as a one of the safest.[16] Clearly, measures of vertical inequality fail to fully illuminate a causal argument for the outbreak of violence.

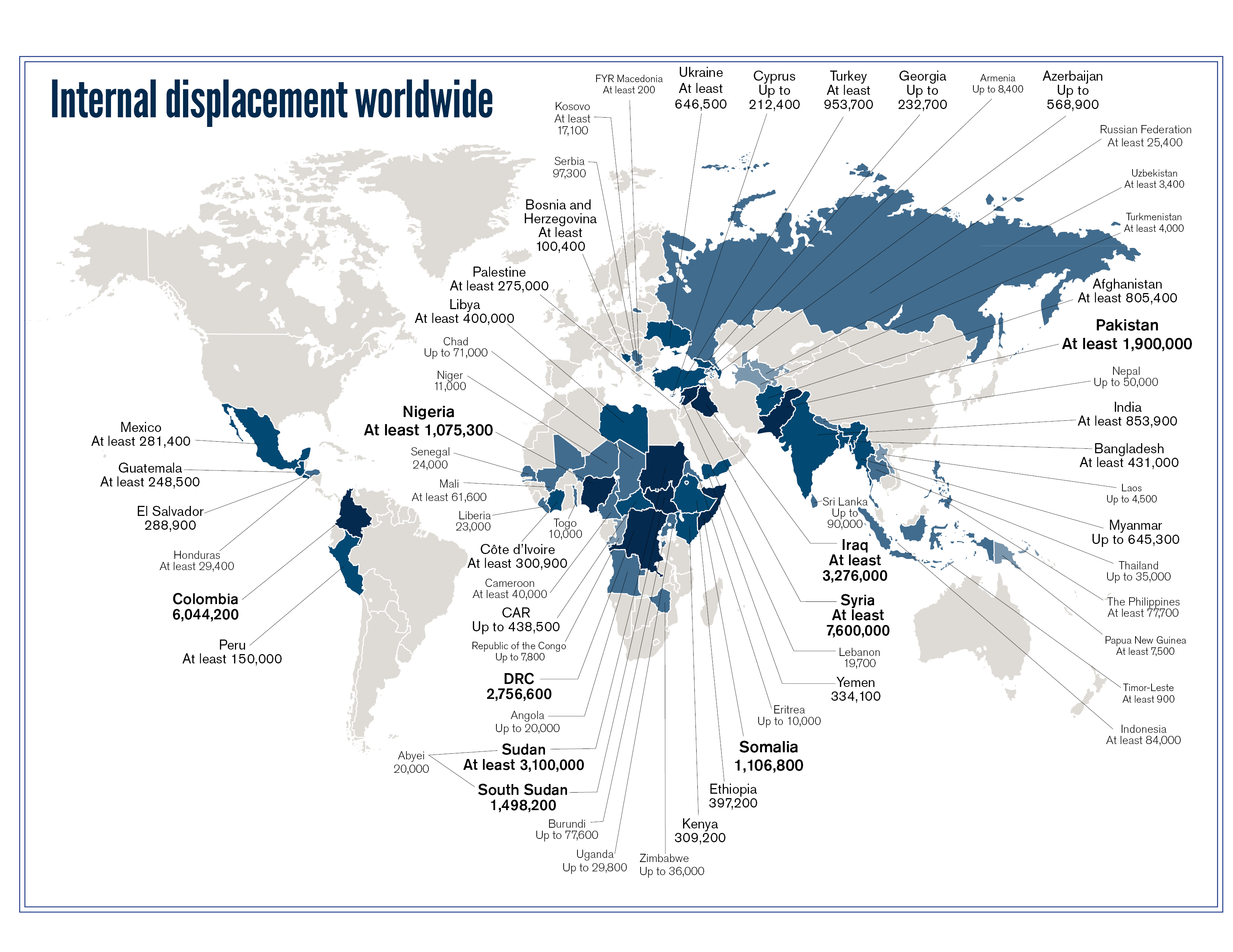

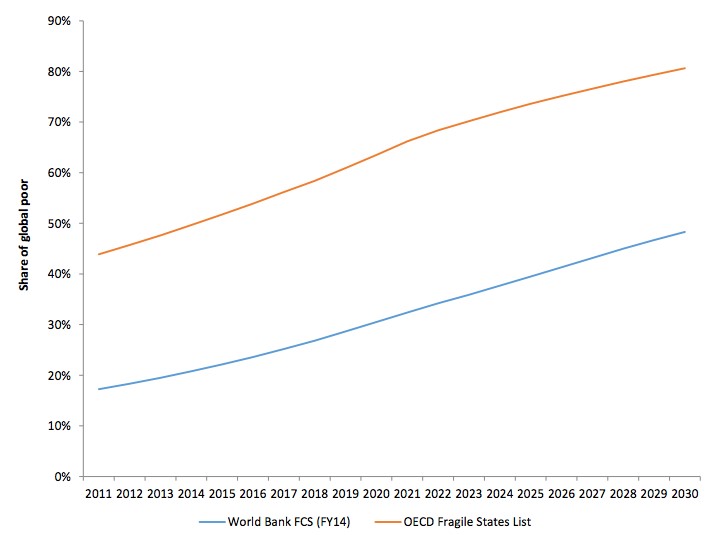

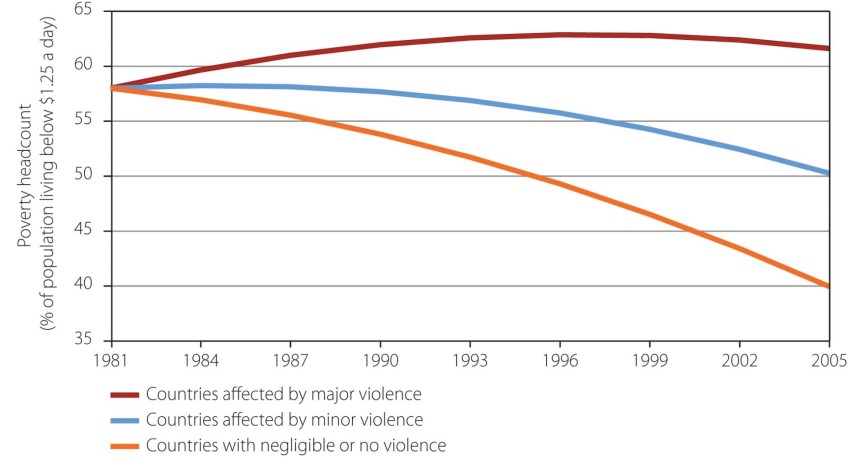

The world spins madly on in the new millennium, “conflicts have increased sharply since 2010” with active conflicts jumping from 41 to 50 from 2014 to 2015 alone.[17] New conflicts are marked by an “increasing concentration of the impoverished in countries affected by violence” (see Figure 3).[18] The report also notes that the longer a country is involved in war, the deeper the depths of poverty become over time (see Figure 4).[19] At first glance, the correlation of the geography of the poor and conflict seemingly suggests a causal relationship. Yet, a “chicken and egg” problem emerges: are wars starting because nations are increasingly poor or are they poor because wars continue?

Figure 3: Percent Share of Global Power Plotted Against Fragile State Index [20]

Figure 4: Poverty Headcount (% of population under $1.25 a day) Over Time[21]

Horizontal inequality may provide the detail needed to better understand the relationship between onsets of conflict and inequality. Defined by Frances Stewart as the “multidimensional” measure of inequalities “between culturally defined groups,” divided into four categories: economic, social, political, and cultural status. [22] Economic horizontal inequality is “access and ownership of assets.”[23] Social horizontal inequalities are marked by the availability and access of social services.[24] Political horizontal inequalities are the “distribution of political opportunities and power among groups.”[25] Lastly, cultural status horizontal inequalities “include disparities in the recognition and standing of different groups’ languages, customs, norms and practices.”[26] Taken together, horizontal inequalities, or “categorical inequalities,” persist for generations as one group seizes an advantage initially and secures a “cumulative” advantage over time thereby solidifying their relative control of a particular resource.[27]

Empirical evidence emphasizes the centrality of horizontal inequalities in the outbreak of violent conflict. Stewart found “the probability of conflict increases threefold” when comparing counties with average economic and social horizontal inequalities with those in the 95th percentile and this level maintains with consistency of higher horizontal inequalities in the political, economic, and social spheres.[28] Essentially, if a group is able to maintain some degree of control within one of those three spheres, the chance of conflict is less likely as the deprivation is less complete.[29] Ultimately, it is precisely this mass “socioeconomic deprivation” that drives the production of a “mass grievance” that can trigger organized opposition and possibly violence.[30]

Gudrun Østby finds further damning numbers for the combustible qualities of horizontal inequalities. Evaluating the averages across the global spectrum, Østby finds that probability for the trigger of a violent conflict rests around a 2.3% amongst nations average in horizontal inequality, but when adjusting the variables of horizontal asset inequality to the 95th percentile, this jumps to 6.1%.[31] Interestingly, Østby finds there may be increased relevance in looking at interregional inequalities, as the addition of 95th percentile of interregional rates of horizontal inequalities leaps the chance of conflict leaps from 3.8% to 9.5%.[32] Lastly, when these horizontal inequalities specifically look at asset allocation by regions, where one region is more benefitted than other, like oil in Western Angola, and there are severe political exclusionary policies in effect, the chance of conflict becomes dramatically high approaching 24%.[33] Horizontal inequalities are certainly kindling high with potential to spark violent conflict.[34]

Yet, the match of conflict is not always sparked; poverty can also translate into “passivity” powered by an overwhelming “sense of voicelessness and powerlessness.”[35] Amartya Sen notes, “many countries have experienced – and continue to experience – the simultaneous presence of economic destitution and political strife.”[36] Not all of these countries face open conflict in their streets as a result of this destitution, thus a causal relationship between inequality and violence remains dubious.

Morris Miller instead argues that the “siren song” of leaders draws people to war emphasizing the considerable barriers, both financial and organizational, that the impoverished face in initiating and ultimately waging war.[37] First, leaders are able to “[stir] up chauvinism and/or grievances by virtue of control of media.”[38] Second, leaders have “recourse to motivation” through a variety of means to incentivize or force participation in conflict.[39] Lastly, making and waging war is an “exceptionally costly process” in human and financial terms.[40] Leaders certainly matter, but the groundswell for action is foundationally related to the grievances of the people, typically rooted in poverty and inequality.

Therefore, rising inequality may instead be the “warning bells” to conflict.[41] Miller notes that this foundational base of poverty “may give rise to widespread and acute stress for individuals and society at large.”[42] This may then lead to conflict through what Ted Gurr calls, “relative deprivation.”[43] He defines this as: “…perceived discrepancy between men’s value expectations and their value capabilities.”[44] He argues that when society provides conditions that cause individuals to have rising expectations and these expectations fail to materialise, the depths of “discontent” deepen across society.[45] Gurr postulates that this intensification of dissatisfaction with the state and the status quo is the match point for sparking the outbreak of violence as particular groups mobilise to prevent a seeming deepening of horizontal inequalities.[46]

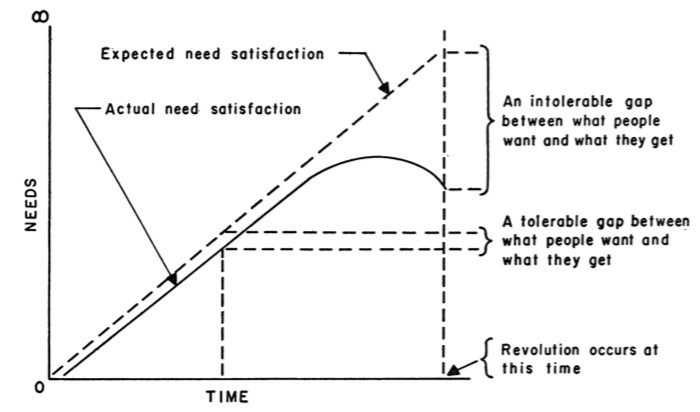

James Davies echoes Gurr arguing that those with the means and “dissatisfied [states] of mind” trigger the onset of violent conflict.[47] He predicts, “revolutions are most likely to occur when a prolonged period of objective economic and social development is followed by a period of sharp reversal.”[48] To visualize this “mood” in a population, Davies depicts the situation through a “J-curve” that illustrates where declining circumstances running headlong into rising expectations spark violence (see Figure 5).[49] Stewart lends her support to this concept, stating “perceived injustices rather than because of measured statistical inequalities…” often catalyse action.[50] Inequality is significant not in its depth in the intensity of which it is felt by the aggrieved.

Figure 5: Need Satisfaction and Revolution[51]

Consider the contemporary example of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Following the 2003 American invasion, Sunnis, previously the dominant political class of Iraq but the minority population comprising about 40% of Iraq’s 38 million people, suddenly found themselves on the outside looking in.[52] Mosul, a majority Sunni city of 1.6 million people, quickly became a nest for the nascent and later fierce Sunni insurgency against the “Sunniphobic” policies of a predominantly Shi’a government in Baghdad.[53] Beyond Sunni identity politics, many officers from the Saddam-era army who refused to serve in the new government migrated to Mosul. In this marriage of mayhem between Ba’athist and Sunni militants, Mosul became home to Al Qaeda in Iraq, under the brutal leadership of Zarqawi, which would ultimately grow into ISIS, and the Jaish Naqshbandi, a militant group led by a close aide to Saddam Hussein.[54] Deep and newfound horizontal inequalities deepened cleavages in Iraqi society, but it is impossible to imagine the conflict without understanding the role of the ideology and leadership of Abu Bakr al Baghdadi and Abu Musab al Zarqaqi as well as the history of foreign intervention in the region. Certainly, the social terrain is an essential factor in the onset of civil war, but it does not occur in a vacuum.[55]

Ultimately, we find that inequality, whether delineated as horizontal or vertical, is an incapable “lone ranger.” Empirical data presented by Stewart and Østby clearly build on the case for the importance of understanding relative horizontal inequalities in the onset of conflict. Work by the World Bank and United Nations provide a macro view to the eradication of vertical inequality. Yet, as Sen and Cramer argue, a direct causal or smoking gun indicator tying inequality to the outbreak of conflict remains missing. To fully understand then, one must analyse the role of leaders, expectations, and market factors alongside and as a part of vertical and horizontal inequality, because, in the words of Amartya Sen, these interconnections that “work together” do so “often kill together.”[56]

Zach Beecher is an MA candidate in Conflict, Security & Development at King’s College London. He focuses on rule of law efforts, counterinsurgency, and post-conflict stabilisation. Previous to his time at King’s, Zach served with the United States Army; in 2017, he was the Lead Logistics Advise and Assist Coordinator for the 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 82nd Airborne Division during combat operations in Northern Iraq. He is a graduate of Princeton University. You can reach him for questions at [email protected].

Notes:

[1] Sen, A. (2008). Violence, Identity and Poverty. Journal of Peace Research, 45(1), p. 12. He uses this to describe the role of deprivation, but I specify its application to the general role of inequality.

[2] Currie - Alder, Bruce and Ravi Kanbur, David M. Malone, and Rohinton Medhora. International Development: Ideas Experiences, and Prospects. “Chapter 6: Inequality and Development.” Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: April 2014.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank (2015). Prosperity for All: Ending Extreme Poverty. Washington, D.C., p.1.

[6] World Bank. (2016). Poverty Overview. [online] The World Bank defines extreme poverty as those persons on an income of less than $1.25 (USD) a day. Poverty persists in sub-Saharan Africa continues with little reduction placing the recent reduction at only 4 million of a larger estimated 389 million.

[7] Stewart, F. (2002). Horizontal inequalities: A Neglected Dimension of Development. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER. P. 1.

[8] Prosperity for All: Ending Extreme Poverty, p. 1.

[9] United Nations Development Programme. (2013). Income Gini coefficient | Human Development Reports. [online] The World Bank and United Nations define the income Gini Coefficient as: “Measure of the deviation of the distribution of income among individuals or households within a country from a perfect distribution, a 0 indicates perfect equality, while a 100 indicates absolute inequality.”

[10] Cramer, C. (2003). “Does Inequality Cause Conflict?” Journal of International Development, 15(5), pp. 401 - 402. Here, he is working with the inequality data from Deningerger and Squire (1996) and the conflict data from Sambanis (2000). It should be noted that Panama faced interstate war in 1990 and Guinea-Bissau experienced some violence in its local region during the late 1990s.

[11] Cramer, 401 - 402. At the time of writing for Cramer, he identified a murder rate of 20 per 100,000. Currently, as recently as 2016, Forbes reported that the number of murders or actions with lethal intent in Brazil eclipsed 58,000, greater than those killed in Syria, a nation currently engaged in a civil war. Reported by Kenneth Rapoza, “As Crime Wave Hits Brazil, Daily Death Toll Tops Syria.” Forbes. Online. Published 28 October 2016.

[12] Ibid., 403.

[13] Cramer., 403.

[14] Ibid.., 403.

[15] Ibid., 403. At the time of Cramer’s writing, Venezuela was in a vastly different civil situation.

[16] Sen, 9.

[17] Marc, A. (2015). Conflict and Violence in the 21st Century: Current Trends as Observed in Empirical Research and Statistics. Slide 2.

[18] Ibid., Slide 2. In this assessment, Alexandre Marc plots the geographic locations of the impoverished outlined in the “Prosperity for All: Ending Extreme Poverty” report by the Development Economics Group at the World Bank in 2014 and plots it against the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development Fragile States Index.

[19] Marc., Slide 17. By Marc’s analysis, he argues that “a civil war costs a medium-sized developing country the equivalent of 30 years of GDP growth.”

[20] Ibid., Slide 16.

[21] Ibid., Slide 17.

[22] Stewart, UNU - WIDER, p. 2. and Stewart, Frances. Horizontal Inequalities as a cause of conflict. (2009). Bradford Development Lecture, p. 5.

[23] Ibid., 5.

[24] Ibid., 5.

[25] Ibid., 5.

[26] Ibid., 5.

[27] Currie- Alder, Bruce and Ravi Kanbur, David M. Malone.

[28] Stewart, Bradford Development Lecture, p. 7.

[29] Ibid., p. 9.

[30] Stewart, Bradford Development Lecture, p. 9.

[31] Østby, G. (2007). Horizontal Inequalities, Political Environment, And Civil Conflict : Evidence From 55 Developing Countries, 1986-2003. Policy Research Working Papers. p, 20.

[32] Ibid., 20.

[33] Ibid., 23.

[34] Østby, 24 – 25. She identifies two major concerns with her analysis. First, the data is drawn from a limited pool of surveys conducted from only 1986 to 2003. Second, there may be errors in “operationalization” of specific variables.

[35] Ibid., 275.

[36] Sen, 7.

[37] Miller, 276.

[38] Miller, 276.

[39] Ibid. 276.

[40] Ibid., 276.

[41] Miller, 278.

[42] Ibid., 291.

[43] Gurr, T. (2016). Why men rebel. London: Routledge, p. 33.

[44] Gurr, 33. He defines value expectations as, “the goods and conditions of life to which people believe they are rightfully entitled” and value capabilities as, “the goods and conditions they think they are capable of attaining or maintaining, given the social means available to them.”

[45] Gurr, 33.

[46] Ibid., 33.

[47] Davies, J. (1962). Toward a Theory of Revolution. American Sociological Review, 27(1), p. 6.

[48] Ibid., 6. He defines revolution as: “violent civil disturbances that cause the displacement of one ruling group by another that has a broader popular basis for support.”

[49] Ibid, 6.

[50] Stewart, UNU-WIDER, p. 15.

[51] Ibid., 6.

[52] Central Intelligence Agency. “Iraq.” The World Factbook. 21 June 2017. Online. and Hashim, Ahmed. (2006). Insurgency and Counter-Insurgency in Iraq. New York: Cornell University Press. Page 237.

[53] Fishman, Brian H. (2016). The Master Plan: ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and the Jihadi Strategy for Final Victory. New Haven: Yale University Press. Page 183.

[54] Parker, Ned and Raheem Salman. (14 June 2014). “Fall of Mosul aided by Iraq’s political distrust.” Reuters. Online.

[55] Gubler and Selway, 227.

[56] Sen, 11.

Image Source: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/12/syrias-war-80-in-poverty-life-expectancy-cut-by-20-years-200bn-lost#img-1

Bibliography:

Central Intelligence Agency. “Iraq.” The World Factbook. 21 June 2017. Online.

Corcoran, Mary (1995). “Rags to Rags: Poverty and Mobility in the United States,” Annual Review of Sociology, 21: pp. 237 – 267.

Cramer, C. (2003). “Does Inequality Cause Conflict?” Journal of International Development, 15(5), pp.397 - 412.

Currie- Alder, Bruce and Ravi Kanbur, David M. Malone, and Rohinton Medhora. International Development: Ideas Experiences, and Prospects. “Chapter 6: Inequality and Development.” Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: April 2014.

Davies, J. (1962). “Toward a Theory of Revolution.” American Sociological Review, 27(1), p.5.

Fishman, Brian H. (2016). The Master Plan: ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and the Jihadi Strategy for Final Victory. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Gubler, J. and Selway, J. (2012). “Horizontal Inequality, Crosscutting Cleavages, and Civil War.” Journal of Conflict Resolution, 56(2), pp.206-232.

Gurr, T. (2016). Why men rebel. London: Routledge.

Hashim, Ahmed. (2006). Insurgency and Counter-Insurgency in Iraq. New York: Cornell University Press.

International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank (2015). Prosperity for All: Ending Extreme Poverty. Washington, D.C., p.1.

Marc, A. (2015). Conflict and Violence in the 21st Century: Current Trends as Observed in Empirical Research and Statistics.

Miller, M. (2000). “Poverty as a cause of wars?” Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 25(4), pp.273-297.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (2014). Highlights: States of Fragility 2014 - Meeting Post 2014 Ambitions. The Development Assistance Committee.

Østby, G. (2007). “Horizontal Inequalities, Political Environment, And Civil Conflict : Evidence From 55 Developing Countries, 1986-2003.” Policy Research Working Papers.

Parker, Ned and Raheem Salman. (14 June 2014). “Fall of Mosul aided by Iraq’s political distrust.” Reuters. Online.

Paul, C., Clarke, C., Grill, B. and Dunigan, M. (2013). Paths to Victory: Detailed Insurgency Case Studies. RAND Corporation, Chapter: Angola (UNITA), 1975 2002 Case Outcome: COIN Win.

Rapoza, K. (2016). “As Crime Wave Hits Brazil, Daily Death Toll Tops Syria.” [online] Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/kenrapoza/2016/10/28/as-crime-wave-hits-brazil-daily-death-toll-tops-syria.

Sen, A. (2008). “Violence, Identity and Poverty.” Journal of Peace Research, 45(1), pp.5 - 15.

Stewart, F. (2002). Horizontal inequalities: A Neglected Dimension of Development. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER.

Stewart, Frances. Horizontal Inequalities as a cause of conflict. (2009). Bradford Development Lecture.

United Nations (2000). Resolution 55/2: Millennium Declaration. New York: United Nations, p.1.

United Nations Development Programme. (2013). Income Gini coefficient | Human Development Reports. [online] Available at: http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/income-gini-coefficient.

World Bank. (2016). Poverty Overview. [online] Available at: http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/overview.