By Lenoy Barkai

On 7 December 2018, fifteen Peacekeepers from the United Nations Organisation Stabilisation Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUSCO) were killed when armed rebels attacked one of their forward operating bases in North Kivu.[1] The attack raised the estimated death toll of UN Peacekeepers killed in malicious attacks in 2017 to 53, with the vast majority of deaths emanating from the UN’s missions to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Somalia and Central African Republic.[2] In response to the escalating security situation, the UN’s Departments of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) and Field Support (DFS) commissioned an independent study into the security protocols for UN Peacekeeping operations.[3] While the study’s key recommendations centred on enabling a more emphatic use of force amongst UN Peacekeeping personnel, the implications thereof are fraught with ethical landmines.

A worrying trend

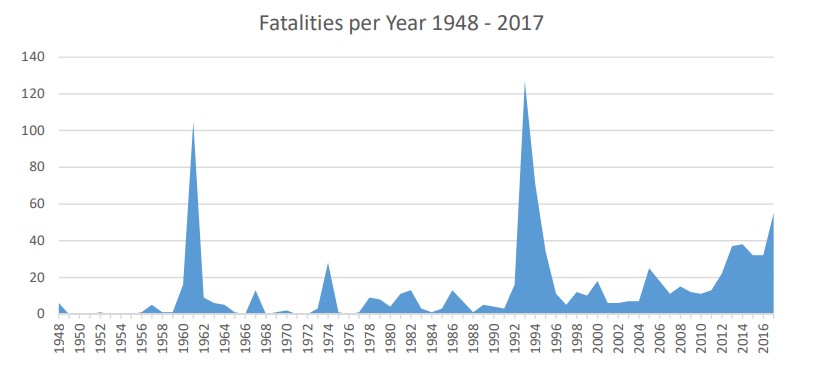

Although a key tenant of UN Peacekeeping Missions is the “non-use of force except in self-defence and defence of the mandate,”[4] certain missions operating in more hostile regions, such as MONUSCO in the DRC, have received the extended mandate of using “all necessary means”, which includes the use of force to fulfil their missions. Nevertheless, security continues to be one of the UN Peacekeeping Mission’s greatest challenges. Since its first mission in 1948, the UN has lost over 900 Peacekeepers due to malicious attacks.[5] While isolated conflicts in the past have marked temporary spikes in Peacekeeper fatalities, a worrying gradual uptick has emerged since 2007:[6]

The blue helmet no longer offers “natural protection”

The independent study into UN Peacekeeping security protocol was published in December 2017, and its authors found much room for improvement. Criticisms included: a proclivity for inaction in the face of bureaucracy and operational inertia, lack of training, poor understanding of the threat environment, resistance to culture-change and a lack of accountability. Perhaps the most stand-out criticism pertained to the outdated “mind-set” of UN Peacekeepers and their leaders. “Overall,” conclude the authors, “the United Nations and Troop- and Police-Contributing Countries need to adapt to a new reality: the blue helmet and the United Nations flag no longer offer ‘natural’ protection’”. Nowadays, UN Peacekeepers face security threats from groups and individuals who do not distinguish between soldiers, civilians and Peacekeepers in selecting their targets. In fact, the report suggests, the UN Peacekeeping Mission’s essential non-combative and ostensibly apolitical nature, makes it a more attractive target for indiscriminate militant groups.

Meeting force with force, and the ethical tug-of-war

The remedy to this, conclude the authors, is a drastic change in the mind-sets of UN Peacekeeping Mission personnel and leadership. This mind-set shift comprises a move away from the organisation’s current defensive and restrained posture. Rather, when faced with security threats, UN Peacekeepers should adopt an active willingness and readiness to use “overwhelming force” so as to bring an end the “impunity” of their attackers. Unless they do so, claim the authors, UN Peacekeepers will continue to be regarded as soft targets by terrorists, militias and other hostile groups. They therefore recommend that UN bases be demarcated by “clearly-defined security zones”, sending a strong message to local communities and other regional actors that there will be “zero tolerance” for security threats in these areas.

In identifying this security “failure” on the part of UN Peacekeeping Missions, the authors place the UN at the heart of the dilemma faced by governments the world over when it comes to asymmetric warfare. How does one deal with a threat actor whose “rules of engagement” directly challenge the norms of war that one takes to be the fundamental principles thereof? Ronald Kuerbitz[7] asserts that traditional warfare is determined by two such principles: “military necessity and humanitarianism.” While conventional war is subject to such “prescriptive norms,” terrorist groups and armed militia frequently shift this normative paradigm by attacking soft targets such as civilians and Peacekeepers. In this way, they are able to strategically relocate the “terms of war” into a normatively problematic arena for their opponents, be they states or multinational organisations such as the UN. This is particularly problematic for the members of Peacekeeping Missions, where the absence of war constitutes their very mandate. In the tug-of-war for moral high-grounds, it is at the very point when the militant group is able to draw its adversary into committing acts on par with its own that it gains the upper hand in terms of delegitimising its opponent. By following the authors’ recommendations, UN Peacekeeping Missions risk falling into this very trap. While great care may be taken to ensure the use of force by Peacekeepers is situationally justified, the grey areas, and room for error, are likely to be significant. Before changing course in this way, the UN should consider the long-term implications for UN Peacekeeping legitimacy should a cultural mind-set shift take place which sees Peacekeepers become trigger-happy versus trigger-shy.

An intelligence-first approach

However, this is not to say that Peacekeepers should continue operating in high-risk environments under the status quo. Before resorting to “overwhelming force”, the security implications of improving the UN’s understanding and application of their threat environment should be fully explored. One of the primary criticisms of the report was that UN Peacekeeping Mission intelligence is “unable to provide timely information that could help prevent, avoid and respond to attack.” The authors describe UN Peacekeeping Mission intelligence as frequently “incomplete”, with knowledge gaps pertaining to the presence, intent, and capability of regional threat actors. Furthermore, where threat assessments do exist these are rarely translated into “operational/tactical activities”.

A thorough overhaul of extant intelligence gathering and risk analysis protocols, replaced with robust, ongoing reporting and intelligence briefings combining both Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) and Human Intelligence (HUMINT) sources, is likely to significantly improve both the safety of on-the-ground personnel and the ability for leadership to take swift, informed and considered action in the face of security threats. Such an approach has the added advantage of enabling Peacekeeping operations. While increasing the use of force risks alienating local communities and delegitimising the Peacekeeping mandate, an enhanced understanding of the threat environment can only work to improve and optimise the efficacy of Peacekeeping operations. With this in mind, the UN may be far better served by developing a robust, relevant and timely intelligence and risk analysis apparatus before encouraging their Peacekeepers to shoot-to-kill.

UN Peacekeeping: most fatal missions from malicious attacks[8]

| Mission Name | Region | Total Fatalities by Malicious attack (as at Feb 2018) | Date of Operation |

| ONUC, MONUC, MONUSCO | (Democratic) Republic of Congo | 203 | 1960 - 1964; 1999 - present |

| UNOSOM | Somalia | 114 | 1993-1995 |

| MINUSMA | Mali | 99 | 2013 - present |

| UNIFIL | Lebanon | 93 | 1978 - present |

| UNPROFOR | Croatia and in Bosnia and Herzegovina | 74 | 1992-1995 |

| UNAMID | Darfur | 73 | 2007 - present |

| UNEF | Egypt/Gaza/Israel | 35 | 1956 - 1967; 1973 - 1979 |

| MINUSCA | Central African Republic | 28 | 2014 - present |

| UNTSO | Middle East | 26 | 1948 - present |

| UNTAC | Cambodia | 25 | 1992 - 1993 |

| UNAMSIL | Sierra Leone | 17 | 1999 - 2006 |

| MINUSTAH | Haiti | 15 | 2004 - 2017 |

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | 15 | 1964 - present |

| UNAMIR | Rwanda | 14 | 1993 - 1996 |

| UNMISS | South Sudan | 13 | 2011 - present |

| UNMIK | Kosovo | 12 | 1999 - present |

| UNOCI | Côte d’Ivoire | 11 | 2004 - 2017 |

Lenoy Barkai is an Associate at S-RM, a risk consulting firm specialising in the management of security, operational, regulatory and reputational risks. Prior to joining S-RM, Lenoy completed her MA in International Relations at the Department of War Studies at King’s College London, where her research focused on political violence, counterterrorism and human rights.

Notes

[1] ‘At least 15 U.N. peacekeepers killed in attack in Congo’, The Washington Post, 08 December 2017.

[2] Source: https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/principles-of-peacekeeping

[3] ‘New Improving Security Peacekeeping Project’, UN, 01 August 2017.

[4] ‘New Improving Security Peacekeeping Project’, UN, 01 August 2017.

[5] Source: https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/statsbyyearincidenttype_5_7.pdf

[6] Source: Improving Security of United Nations Peacekeepers: We need to change the way we are doing business’ UN Commissioned Independent Report, 19 December 2017.

[7] Kuerbitz, R. (1988) The bombing of Harrods: Norms against civilian targeting. In Reisman, W. M. & Willard, A. R. (eds.) International incidents: The law that counts in world politics. Princeton, Princeton University Press, pp. 238-262.

[8] Source: Peacekeeping.un.org/en/fatalities

Image Source: here