by Cristina Romero-Caballero Cuttell

Source: Council of Europe

Migrants embarking in unseaworthy boats from Northern and Western African shores or making arduous overland journeys on foot from Middle Eastern countries, such as Syria or Afghanistan, to reach Europe demonstrate the harsh reality of irregular migration. These movements are normally prompted by the perilous circumstances such as wars, ethnical violence or scarcity of essential resources affecting their home countries.

In addition to their tough past and uncertain future, many migrants find themselves alone and vulnerable in foreign lands, often enduring dangerous, inhumane, and degrading circumstances caused by governmental policies where they arrive. For its part, the EU continues to turn a blind eye to the humanitarian issues underlying such migratory movements, focusing mainly on the associated security and logistical matters. This failure to give help where it is most needed is causing extreme suffering at its borders, proving the lack of empathy and solidarity of EU migration laws and regulations towards the arrivals.

The EU aims to show on occasions, the apparent importance it places on safeguarding migrants, leading the European population to believe its actions are sufficient. Germany´s decision in 2019 to take in vulnerable refugees through the European Resettlement Programme, and the provision of EU aid to Turkey to support refugees escaping from Syria, are just some examples. Both overtures initially appear altruistic; yet closer examination reveals they are, by all accounts, insufficient. In March 2020, when the unsustainable situation in Turkey led it to threaten to allow migrants to cross the border into Greece, the EU acted swiftly by providing aid to Greece to seal its Turkish borders. This response was not born from a spirit of goodwill and solidarity; as expected, the EU was simply trying to secure its borders to prevent a reignition of the 2015 crisis. Likewise, the response from other powerful European actors, such as the UK and France, to the plight of migrants has been begrudging at best, and shameful at worst, as exemplified by the recent drownings in the English Channel.

Such a lacklustre response is a deeply controversial issue as the EU aims to protect the interests of all Europeans by ensuring their safety and economic growth; but it fails to do enough for the displaced, asylum-seekers, refugees and migrants. The EU is, in effect, preventing genuine refugees from seeking asylum through laws that disregard outsiders by complicating and slowing down such processes, as dictated, for instance, by the Dublin Regulation. Such law, only permits refugees to seek asylum in the country where they arrive, leaving many without protection since the receiving countries, such as Greece, Italy, Malta or Spain, are overwhelmed. Furthermore, through such laws, refugees are being denied their right to freely choose where to live. Denying such protection and freedom is in breach of the human rights upheld by international law through the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, and the 1990 Migrant Workers Convention. This insular and nationalistic approach is dehumanising the lives of those escaping from wars, genocides, terrorist regimes, and the effects of climate change in order to find a place where they can live, instead of remaining in one where they are simply trying to survive.

To confront African migration, the EU is seeking to establish Migration Agreements with third countries in Northern Africa, the ultimate territorial border before the Mediterranean and, hence, European waters. The strong relationship established with Morocco attests to this. Since the 1990s, a series of bilateral re-admission agreements have been signed between Morocco and Spain to cooperate in the control of irregular migration. This cooperation was later complemented by FRONTEX, the EU External Border Agency. In 2013, a new tool was put forward to North African countries as part of the EU Global Approach to Migration. This ‘Mobility Partnerships Facility’, a “long-term framework based on political dialogue and operational cooperation” for collaboration on migration, was accepted by Morocco and Tunisia. Although certain aspects have not yet been finalised, including the controversial readmission issue of third-country nationals (TCN), its implications are visible: higher securitization, and stricter border controls.

Source: International Organization for Migration

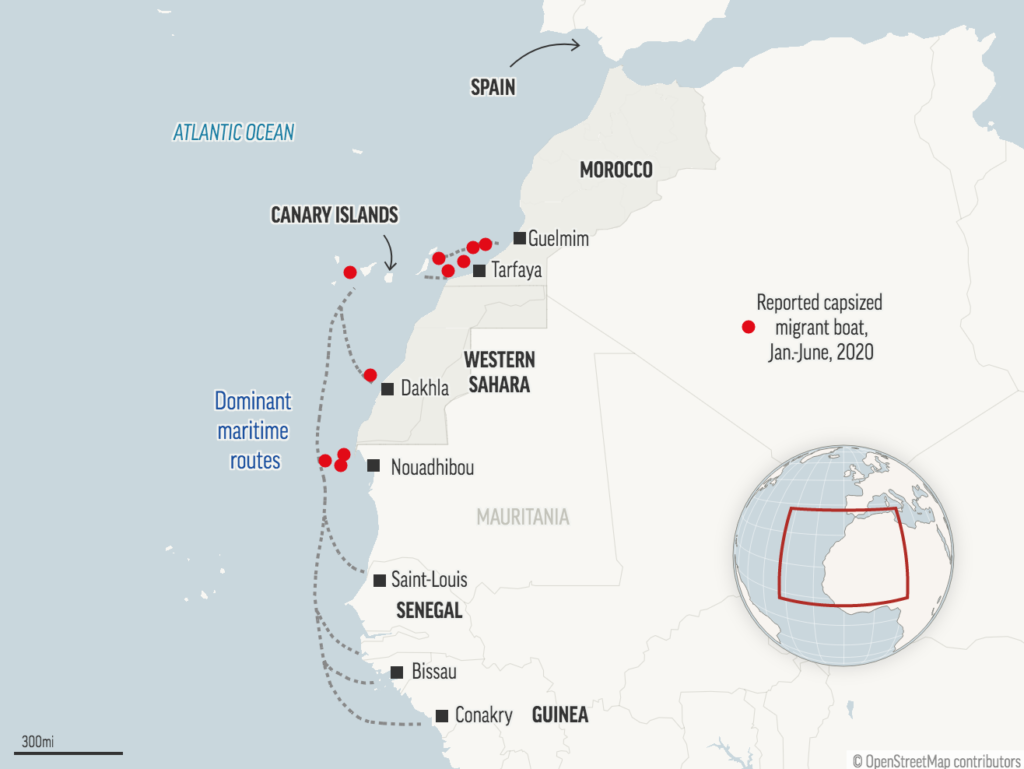

What sounds like a great step forward in helping Morocco to manage the large influx of migrants is, in reality, just shifting part of the migratory issue from the north of Morocco to the south and west, and to southern Sub-Saharan countries such as Senegal, Gambia, and Mauritania, where less control exists. Thus, migrants seeking a better life in Europe now view the more dangerous West African Maritime route, crossing to Spain’s Canary Islands from Africa’s Western Coast, as their only viable option. This is a route that has witnessed over five hundred deaths in 2020, a figure which is likely much higher as not all shipwrecks are reported. Despite the patrols between the archipelago and the African coast, the abundancy of boats has overwhelmed the islands’ rescue and humanitarian services.

As a result, the Canary Islands are currently suffering a humanitarian emergency and Europe is once again ignoring another migratory issue affecting its southern border. Migrant arrivals in Spain’s Canary Islands are at their highest level in over a decade. Although the number of migrants arriving in Spain via the Mediterranean Sea has decreased by fifty per cent versus 2019, arrivals in the Canaries have increased by more than a thousand per cent. These are shocking numbers, but they fail to reflect the reality of the harsh journey as one in every sixteen migrants who embarks upon this gruelling journey dies along the way. For example, on 24 October 2020, a boat caught fire off the coast of Senegal and almost all of its 140 occupants drowned.

Problems do not end upon reaching land as Canary Island authorities lack the capacity to manage the enormous influx of migrants. Gran Canaria is the island feeling the heaviest toll, with its reception centres full and over two-thousand people at a time forced to camp on the dockside in the port of Arguineguin. Concurrently, this humanitarian crisis is impeding the maintenance of coronavirus prevention measures, putting at risk the lives of migrants and those involved in their rescue and care. Moreover, due to tedious bureaucratic and legal procedures, further hampered by COVID-19, these migrants are facing another deadlock as the Spanish government has hindered their transfer to other Spanish regions to prevent the establishment of a new migratory route into Europe. This, together with the closure of African countries’ borders due to the pandemic, is effectively converting the islands into an open-air prison for the 18,000 freedom-seekers currently being held on them, mirroring the appalling situation on the Greek island of Lesbos.

The Spanish Government and the EU both believe that protection should only be provided to those who have the right to it and those who comply with the Dublin Regulation. A study on arrivals in the Canary Islands completed by the UN Refugee Agency in 2020 revealed that over sixty-two per cent were escaping from generalised, gender-based, ethnic, religious or political violence, hence having the right to seek asylum; therefore, Spain and the EU are duty-bound to come to their aid. Nevertheless, there are also, the so-called economic migrants, escaping from the hardship exacerbated by COVID-19 in their home countries. This group is not entitled to international protection and such migrants are liable for deportation to their countries of origin.

To some extent, the caution shown by the Spanish authorities and the EU when handling the irregular arrivals is understandable. Whilst some are genuine refugees, striving to reach a destination where their life is not in danger, this does not assuage the fears of the Spanish government and the EU that some may be members of criminal groups, thereby endangering the security of Europe. For this reason, two measures are required: procedures that ensure protection is provided to all those entitled to it under international law; and, in parallel, the creation of safe deportation routes. Without these improvements to guarantee a dignified response, Gran Canaria risks suffering a similar humanitarian catastrophe to the one befalling Lesbos.

Although logistical processes have commenced, with migrants finally being transferred to tourist complexes unoccupied due to COVID-19, and receiving more dignified shelter, the problem remains unresolved as very few migrants are being transferred to other parts of Spain or Europe, or extradited, due to European and Spanish bureaucracy and the pandemic. Unsurprisingly, some experts suggest that a “Call Effect” has been created, as migrants encourage others to make the dangerous journey, putting further strain on the Spanish system, and placing more lives at risk. Consequently, collaboration between the EU, Spain, and African countries to address the underlying factors spurring migration in the countries of origin is the only way forward. It will not be easy, but the push factors driving migrants from Northern Africa to make the perilous voyage to Europe must be addressed to enable a more long-term solution than the piecemeal efforts undertaken to date. Until such a time, the EU’s moral duty must be to offer help and support to all of those who reach its shores.

Cristina Romero-Caballero Cuttell is a part-time MA International Relations student in the Department of War Studies at King’s College London. Her research interests are around the topics of Migration, especially African migration into Europe, Gender and Human Rights. She is currently a Spanish Red Cross volunteer in the Canary Islands helping with the management of the latest influx of migrants to the islands.

Cristina is a part of the Strife Women in Writing Programme.