By Clément Briens

Science fiction’s portrayal of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has very often been centered on the fear of “killer robots” almost always often manufactured by the United States (US) government. The malevolent Skynet AI in the Terminator franchise, for instance, is developed by Cyberdyne Systems, a US military contractor. The AI in I, Robot was also manufactured by a fictional US government contractor- the aptly named US Robots and Mechanical Men Inc. However, reality has strayed from these popular conceptions, as they approach almost half a century of age. The reality is that AI will have many military applications other than “killer robots” as we picture them- and if we ever do see the rise of a Terminator in our lifetimes, they will not be built with Arnold Schwarzenegger’s iconic Austrian accent. Rather, the Terminator will most likely speak Mandarin Chinese.

China’s march towards AI

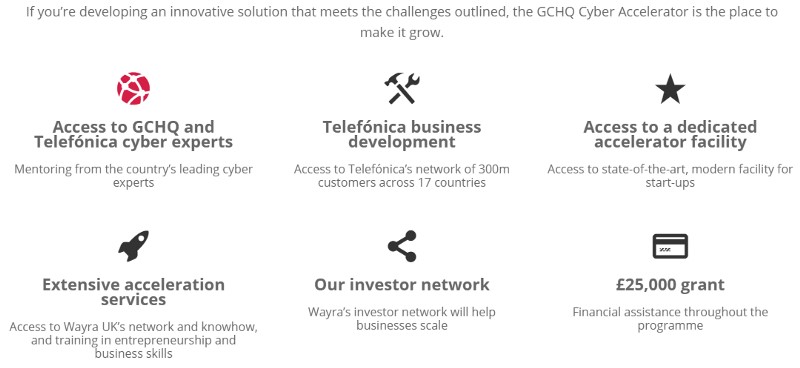

In June 2017, China’s State council released its AI Development Plan- which shows Beijing’s clear intent in boosting its efforts in developing its own AI capabilities. The document reveals China’s ambition to become “the world’s premier AI innovation centre” by 2030- which will likely increase its competitiveness in the economic and military-industrial sectors, a worrying thought for US policymakers. Even more worrying for US leaders is the fact that China will most likely piggyback on US innovation to achieve this, either through industrial espionage, (which China has long history of resorting to); or by legitimately investing in American AI startups (which has already has begun).

Beijing’s dual strategy to fulfil its ambitions is clear. First, it will seek to acquire some of these technologies by investing in the US. While some of these investments may seem like normal Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs) at first glance, the risk remains that AI is a dual-use technology. That is, it “can be used for both civilian and military applications”, such as nuclear power or GPS. Furthermore, dual-use technologies are notoriously hard to control, as demonstrated by the difficulty of the JCPOA negotiations with Iran in 2015. Compliance through inspectors and safeguard mechanisms is difficult, as demonstrated by the alleged construction of underground nuclear enrichment facilities, although its actual existence remains inconclusive. Similar measures to marshal AI research could be just as problematic.

Second, Beijing will not only seek to exploit investments in sensitive US technology firms, it will also look to stimulate its own local start-up community. A report by Eurasia group and Sinnovation Ventures states that “China’s startup scene has transformed dramatically over the past 10 years, from copycat versions of existing applications to true leapfrog innovation”, in part due to “supportive government policies”. This seems to be far from the reality of Washington’s policies with regard to AI, as Donald Trump’s 2019 budget proposal supposedly “wants to cut US public funding of “intelligent systems” by 11 per cent, and overall federal research and development spending by almost a fifth.” Indeed, the Trump presidency lays out a stark future for US development of AI and any hopes of catching up with China.

Terminator or J.A.R.V.I.S.?

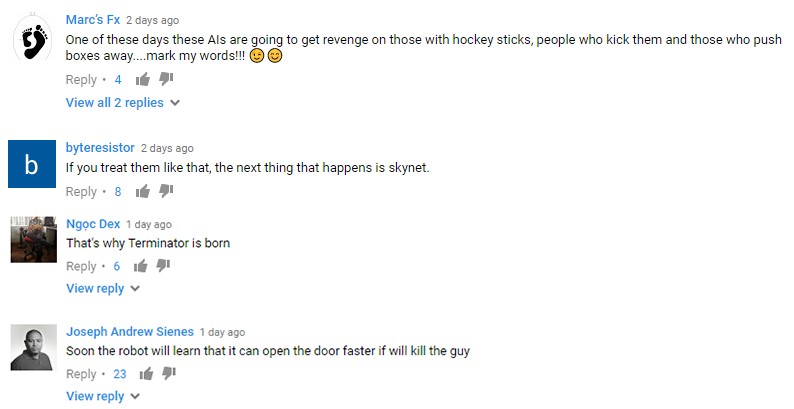

With recent news on China’s advances in AI, it is important to clarify what the security implications of AI may refer to, and to debunk the “killer robot” myth. The public’s main perception of AI is one of “killer robots”, fuelled by the sci-fi portrayals cited above. Boston Dynamics recently published a series of viral videos showing their advances in developing dog-like SpotMini robots mounted with robotic arms. In this video, the robots were capable of taking a beating from a nearby engineer and opening doors. Internet users reacted to these videos with mixed feelings:

Some of these reactions have been much stronger than others. For instance, an open letter by 116 scientists sparked discussions at the United Nations (UN) of a ban on autonomous “AI-empowered” weapons systems. Additionally, campaigns to ban “killer robots” have sparked worldwide.

But while the public fear for Terminator-type killer robots is understandable, as AI-controlled weapons systems cross innumerable ethical and moral lines, other fearful applications of AI exist. The potential for AI-empowered cyber weapons, for example, seems more likely than killer robots, and can have destructive effects that would endanger Western liberal democracy. A report titled “The Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence” outlines the risks that AI poses in helping with the automation of cyber-attacks. Although AI is already being employed as a form of cyber defence, the report outlines how AI can be used to empower “spear phishing”, a technique where hackers target individuals through social engineering in order to obtain passwords and sensitive data.

One can imagine how AI can also be employed in spreading disinformation on a much larger scale and more efficiently than “dumb” botnets. The Internet Research Agency in St. Petersburg, Russia, allegedly had a hand in interfering in the 2016 US Presidential elections. Such troll factories will be a thing of the past as AI will become able to autonomously mimic online profiles by feeding off of huge amounts of data on Twitter and Facebook to automatically formulate opinions, spread political messages and retweet/share disinformation. While the US Department of Justice was able to attribute, identify and indict thirteen of these so-called trolls, attribution of AI-controlled social media accounts will be even harder. Thus, AI-empowered disinformation may have far-reaching consequences on our electoral processes.

How the US can stay ahead

Many are skeptical of the ability of the UN to actually ban autonomous weapon platforms, and the fact that Russia and China would probably not abide by such a ban makes the proposed ban much less endearing to US policymakers.

How then can the US stay on par with China’s rising economic power and its fine-tuned strategy?

Firstly, to remain competitive, the US needs to limit the spread of dual-use AI technology originating from its Silicon Valley laboratories. An unreleased Pentagon report obtained by Reuters highlights the need for the curbing of these risky Chinese investments, which most likely gain access to AI advances without triggering CFIUS (Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States) review. In fact, implementing these proposed reforms from the Pentagon would be a welcome first step for US lawmakers.

Secondly, the US needs to bank on foreign nationals by investing in and retaining top talents. A comprehensive report by Elsa B. Kania for the Center for a New American Security argues that it is “critical to sustain and build upon the current U.S. competitive advantage in human capital through formulating policies to educate and attract top talent”. Modifying immigration laws for top Chinese students in AI and other high-tech domains to allow them to stay after their studies could be a solution to mitigate the “brain-drain” effect that Silicon Valley is currently enduring, and a way to gain an edge on Beijing.

Lastly, the US should also rely on its private sector, in which most of the world’s cutting-edge AI research is taking place. According to a CB Insights report, 39 out of the top 50 AI companies are based in the US. However, the most well-funded of them remains a Chinese firm, ByteDance, which has raised $3.1bn according to the report. The US has a flourishing industry which needs backing from its leaders. With industry leaders such as Google’s DeepMind venture or even Tesla investing billions into AI research, competing with Chinese firms is more than achievable. MIT’s compiled list of the world’s 13 “Smartest” AI ventures lists five US companies as their top 5 picks: NVidia, SpaceX, Amazon, 23andMe, and Alphabet, Google’s parent company.

While the US is still ahead of China in terms of AI research, its rival’s intent and strategy and the lack thereof from the current US administration seems to give it the edge in the next decade of AI research. US allies such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and France have both unveiled AI-oriented national strategies. The Trump administration seems to be lagging behind in presenting an American equivalent of similar scale, despite desperate calls from academics and cybersecurity professionals.

Clément Briens is a second year War Studies & History Bachelor’s degree student. His main interests lie in cyber security, counterinsurgency theory, and nuclear proliferation. You can follow him on Twitter @ClementBriens

Image Source

Banner: https://blogs.spectator.co.uk/2017/08/we-should-regulate-not-ban-killer-robots/

Image 1: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aFuA50H9uek