By David Bruckmeier:

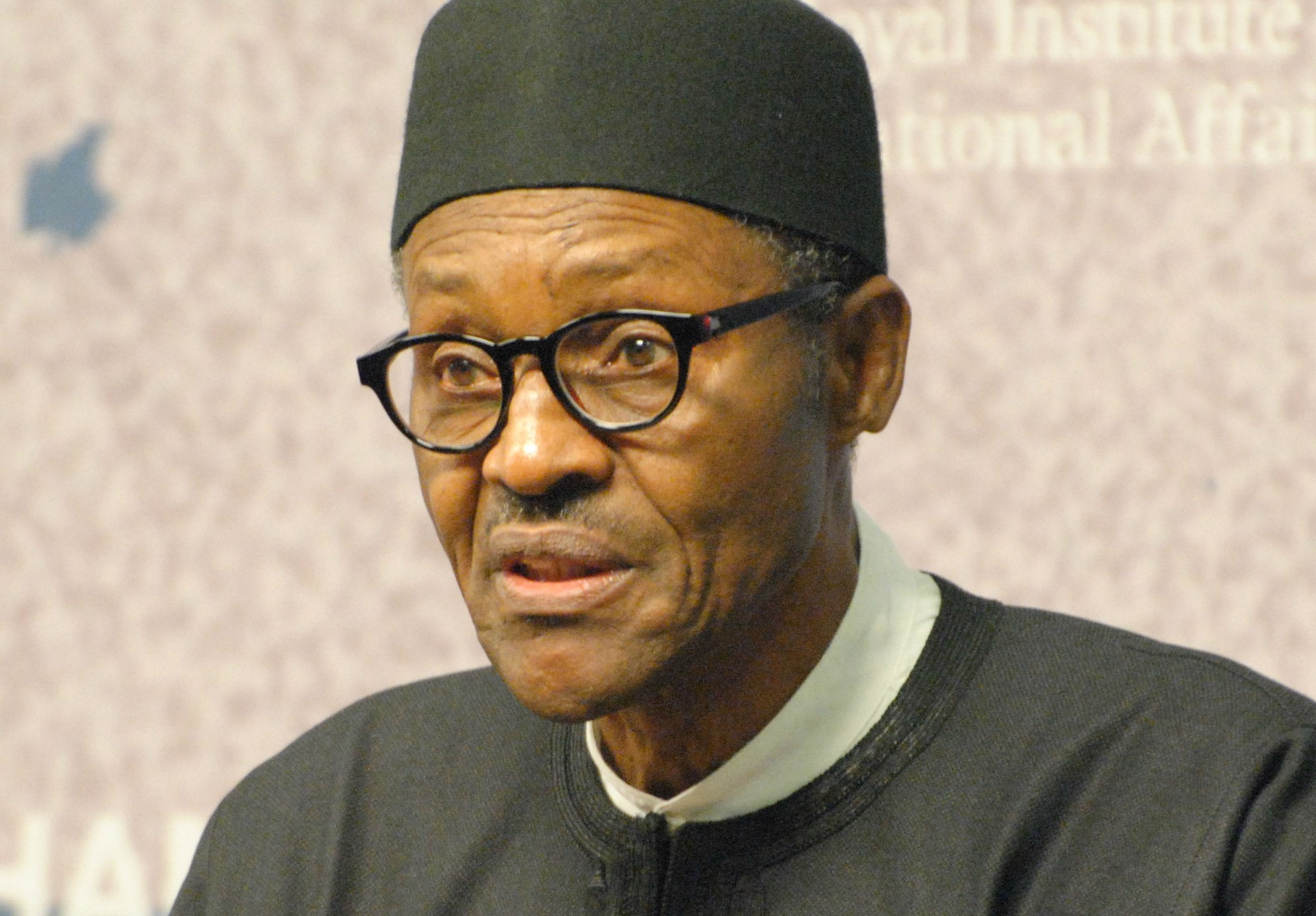

Nigeria’s next president: Muhammadu Buhari. Photo: Chatham House (via Wikimedia Commons)

For Muhammadu Buhari, fourth time’s the charm. After three unsuccessful runs for the Nigerian presidency, the 72-year-old was officially declared winner of last week’s elections with a lead of more than two million votes over his main rival, the incumbent Goodluck Jonathan. It is the first time a ruling president of Nigeria has been replaced through democratic elections rather than a coup. What was different this time, then?

Unlike previous elections, Buhari enjoyed the backing of a large coalition of formerly disparate opposition groups. In the All Progressives Congress (APC), a credible and united alternative to Jonathan’s PDP has emerged for the first time since the reinstitution of civilian rule in 1998. Although it remains to be seen whether the APC survives in the long-term, Buhari’s victory marks the beginning of Nigeria’s transformation into a true multi-party democracy. Moreover, Muslim northerner Buhari managed to win over the predominantly Christian south-west, weakening the sharp north-south, Muslim-Christian divide that has characterised the country’s politics since independence. Among other areas in the south, he prevailed in the most populous state and business hub Lagos, whose widely respected governor had joined the APC.

But Buhari himself was not always so fond of the democratic principles that made his victory possible. From 1983 to 1985, he ruled the country as a military dictator, gaining a reputation for ruthlessly suppressing any opposition to his rule until he was himself ousted by a military coup. Yet when the incoming president is inaugurated on 29 May, he will find himself at the helm of a country that has radically changed since the days of his military dictatorship.

Buhari describes himself as a ‘converted democrat’, and it is unlikely that he would be able to return to his old ways even if he had such intentions. Nigeria now has a vibrant and critical media and a relatively effective, if imperfect, system of checks-and-balances to ensure free elections. Most importantly, as Jonathan’s defeat has shown, it has a well-informed electorate that holds its leaders to account and looks beyond ethnic and religious affiliations on election day. Its political elite seems to have learned as well: in a gesture of goodwill, President Jonathan quickly accepted defeat and congratulated his opponent on his victory. Thus far, there is no sign of a repetition of the riots that marred the 2011 elections.

The challenges Buhari is facing are massive. At the top of the list is the fight against Boko Haram, whose six-year reign of terror has cost over 15,000 lives in north-eastern Nigeria and neighbouring countries. In the election campaign, Buhari frequently attacked the current government for ignoring the Islamist group for too long, a view shared by many observers. A last-minute military campaign against Boko Haram launched by Jonathan just a few days before the original election date was largely perceived as a desperate election stunt. Recent successes against the Islamists have substantially weakened the group but are mostly thanks to Chadian and Nigerien intervention as well as Nigerian-enlisted mercenaries from South Africa. Buhari, who as military commander warded off Chad’s annexation of territories in north-eastern Nigeria, has called the presence of foreign troops on Nigerian soil a disgrace and vowed to eliminate Boko Haram without their assistance.

If Buhari’s promise is to become reality, he will have to shake up Nigeria’s military, once one of Africa’s most competent and powerful. Under Jonathan and his PDP predecessors, it has become the victim of a glaring absence of long-term strategic thinking and rampant corruption. Much of the country’s $6 billion annual military budget never reaches its destination, disappearing instead into the pockets of officials as it passes myriad levels of bureaucracy. The result is a badly equipped and ill-trained army, with reports of human rights abuses by Nigerian troops on the rise. To prevent Boko Haram from simply reverting to its pre-2014 strategy of hit-and-run attacks, a sustainable security strategy must involve the installation of a permanent military and police presence in areas cleared of the terrorist group.

Although his election manifesto was slim on concrete proposals, Buhari has pledged to restore discipline in public administration and fight the country’s endemic corruption. His military background, ascetic demeanour and reputation as a no-nonsense man lends his promises credibility in the eyes of many voters.

Even so, there is no doubt that the fight against Boko Haram cannot be won by military means alone. The group’s rise is primarily the result of massive economic disparities and the disenfranchisement of north-eastern Nigeria’s population from the country’s political and economic elites. Previous governments have neglected the economically insignificant region, allowing the insurgency to grow almost unchecked, and to many residents of Lagos or Abuja, Maiduguri feels no closer than Nairobi. The Jonathan government’s decision to restrict internet and mobile phone access in three north-eastern states in order to curtail Boko Haram’s operations has contributed to the sense of disconnectedness.

As a northerner, Buhari is likely to have a better understanding of the region’s needs than his predecessor. His challenge will be to convince those who did not vote for him that he is their president too. In particular, he will have to be careful not to make enemies in the oil-rich Niger Delta, where another insurgency has only recently calmed down and might flare up again if people feel that their region’s needs are not adequately taken into account.

Trouble looms on the economic front, too. Africa’s largest economy has made strides towards diversification in recent years, but crude oil still accounts for 70% of government revenues. The collapse of the oil price has hit Nigeria’s economy hard, forcing the government to implement significant budget cuts. As a result of decreasing demand for the country’s main commodity, the Naira has depreciated sharply – bad news for a country that imports most consumer goods and, ironically, processed petroleum. Economic turmoil and the threat posed by Boko Haram have driven borrowing costs to an all-time high, putting strains on business and government alike.

In the short term, Buhari will have no choice but to continue with the austerity measures initiated by the current government. In the long-term, further economic diversification and a provident management of oil revenues to provide for bad times must be top priorities for the next president. He has promised to improve the energy supply (identified by voters as the single most important election issue) and infrastructure, but otherwise kept a low profile on economic policy - possibly because his economic track record as military ruler is less than stellar.

The next few years will be crucial to consolidating Nigeria’s status as Africa’s foremost political and economic power. As their country stands at a critical point in its history, Nigerians have taken a leap of faith by electing a former military dictator as their leader. More than anything else, their vote was a remarkable expression of democratic will and a promising sign for national unity. Once he takes power, Buhari will have to flesh out how he intends to turn vague promises into political outcomes. Boko Haram’s elimination is within the realm of possibility. Its roots are local, and if its underlying causes are addressed, the insurgency could be history by the next elections. Nigeria is not a country of miracles, but it has proved doomsayers wrong time and again. If Buhari plays his cards right, there is a strong chance that it will emerge a stronger, safer and more united country.

David Bruckmeier is an MA Student in International Relations at King’s College London. He is particularly interested in African affairs.