This article is a part of our Series on Memory, History, and Power. Read the Series Introduction here.

Jorge Luis Borges, in his essay Funes the Memorious[i], tells us a story of Ireneo Funes, who, after falling off a horse and hitting his head, starts recalling absolutely everything. This is soon revealed to be a curse: unable to connect with others, the world became intolerable to Funes. From its very title, Borges’ essay is a story about the function of memory. ‘We speak so much of memory because there is so little of it left’, says Pierre Nora[ii]. Memory is not the ability to remember everything, but, instead, an acknowledgement that things escape us.

From Borges’ essay, we come to understand that remembering is not an act of accumulating events or sensations. As Funes absorbed literally everything, he was not able to give space to any sort of abstraction. He was unable to imagine. Actually, to keep everything in mind became a heavy curse. Memory requires a degree of abstraction. It demands forgetting, acknowledging that we cannot fully grasp what happened and, with this, understand that it has a fragile matter that necessitates the constant activity of remembering. Memory is, then, an active act of looking for what is already lost and, from that, creating strategies for things not to be forgotten.

In this short essay, I intend to compare memory with the act of sewing: in a delicate exercise of patience, we sew threads until they form a larger fabric, aware of thread’s fragility. Here, we can compare how remembering resembles the ways in which the needle creates connections with other tissues. As the needle aims to connect the tissues together, creating a common piece, memory as well creates a network of elements. In this way, it provides meaning to the world, in other words, it provides a common ground from which we come to understand who we are between past and future.

Here, an interesting parallel can be made to some habits that come from the Afro-Brazilian religion Candomblé. According to these traditions, people carry with them, in wallets or pockets, a piece of tissue which is embroidered with herbs and spices. This amulet or talisman is called patuá and one uses it for luck and protection. Some of these patuás have a relative’s photo on them.

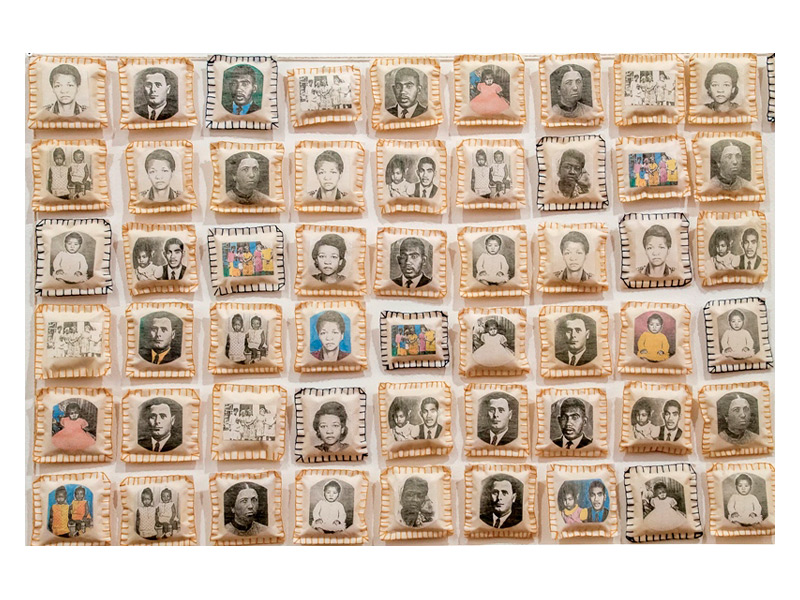

Coming from black origins, the Brazilian artist Rosana Paulino uses elements from Candomblé religious practices to reflect on Brazilian History, highlighting the invisible threads of colonisation that still endure. In the work ‘Wall of Memories’ (1994), Paulino presents us with 1,500 little patuás, carefully sewn, displayed on a bigger wall, with each one of them having a small portrait of a black person or family.

Paulino’s work represents an inquiry into her own story as embedded in Brazil’s uneasy relationship with its past. She denounces the absence of the black population in the collective imagination of the country’s construction, even though most of Brazil’s population has origins related to the black diaspora. As Paulino delicately reveals, black people are reduced to a marginal place in the public sphere, leading to many forms of oppression and violence in contemporary public policies. Her works, then, make visible those hidden in political communities. Investigating her own identity, Paulino turns to a collective history to understand her marginality as a black woman in the country she comes from and lives in.

As viewers, we become aware of those representations that are actually invisible in the social-political fabric of Brazil. This is an attempt by the artist to use visual arts as an exercise of looking at those black people often ignored in the Brazilian context, interrupting, then, perpetuated colonial exclusions from the political sphere. Paulino literally sewed each one of the patuás, embroidery with pictures of eleven unknown families, but which could be one of her ancestors, as she argues. The point here is that the action of connecting threads allows the artist to fill some gaps in the present, disclosing narratives and illuminating hidden histories and subjectivities. In this way, Paulino uses her lived experience, as someone who has black origins, to metaphorically sew a collective memory, since it belongs to a broader context of political dynamics from where she speaks. By that, I am referring to the black experience that still informs how Brazilian society deals with its violent past and current black population[iii]. With her work, Paulino raises a reflection on racism, colonialism and history. As viewers, we have no option left but to think about these sensitives issues when dealing with our past and present, especially as Brazilians.

Although the Brazilian past is full of violence and exclusion against the black population, Paulino goes back to her ancestors to protect her at present. The patuás, then, represent how she honours their history and how this connects with her lived experience. Here, a traditional linear historiography, where past and future are temporal standpoints of a succession of events, enters into the question[iv]. Actually, dealing with present demands looking at collective memories, since there are different ways of approaching the past, and the past works here as a promise of something soon to be revealed – a redemption, according to Walter Benjamin. Benjamin develops this idea of redemption as a moment of awakening, in which one takes into account other perspectives when looking at one own’s history. This awakening implies being sensitive to the ones defeated in history, namely, those who are easily forgotten when great events are told. To him, history is a constellation, which operates by ‘telescop[ing] the past through the present’[v], allowing ‘the past to place the present in a critical condition’[vi]. In Benjamin’s words, ‘it’s not that what is past casts its light on what is present, or what is present casts its light on the past’[vii], but that the past has elements that endure in the present.

Then, the present is a complex constellation assembled by different approaches to the past(s) and this is the reason why the present unfolds into fragmentations and uncertainties[viii]. What is so striking and promising in Benjamin’s philosophical project is the consequence of this fragmented history(ies): it is precisely this struggle of different past appropriations, its uncertainties, that creates a fissure that can make one aware of ones’ own embeddedness in a collective history. With Benjamin, we realise how a linear narrative of history actually contains within itself unknown victims of progress and modernisation. As he states, ‘there is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism’[ix]. Once one realises this constellation, it breaks with the order of the things, namely, the unique version of ‘History’. This movement is what Benjamin calls redemption: awakening, as an enlightened moment, of the dialectical process that configures the present[x]. Looking at Paulino’s work, one realises that those faces permeate a hidden and troubled history of Brazilian modernisation and colonisation.

Hence, as Benjamin states, ‘articulating the past historically does not mean recognizing it “the way it really was.” It means appropriating a memory (Erinnerung) as it flashes up in a moment of danger[xi].’ Against the legacy of oblivion, the patuás from Paulino are a lost treasure of protection, making us aware that memory demands acts of sewing threads that connect us with others[xii]. This is why memory is a fragile matter because we are always at the edge of losing the thread. Still, sewing is all we have left to not forget.

[i] Jorge Luís Borges, “Funes el memorioso,” in Obras completas (Buenos Aires: Emecé, 2007), pp. 583–590.

[ii] Pierre Nora, Les Lieux de Mémoire (Paris: Gallimard, 1984), p.7.

[iii] Paulino, Parede da Memória (Wall of Memories).

[iv] Nora, Les Lieux de Mémoire, p. 43.

[v] Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project. Edited by Rolf Tiedemann. (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2002), p. 741.

[vi] Susan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1989), p. 338.

[vii] Benjamin, The Arcades Project, p. 462.

[viii] Vivienne Jabri, The Postcolonial Subject (New York: Routledge, 2014), p. 15.

[ix] Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, v. 4 - 1938-1940. Translated by Edmund Jephcott and Others. Edited by Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010).

[x] George Didi-Huberman, Images in Spite All: four photographs from Auschwitz (Chicago, US: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

[xi] Benjamin, Selected Writings, v. 4 - 1938-1940, p. 391.

[xii] Jeanne-Marie Gagnebin. História e Narração em Walter Benjamin. (São Paulo: Perspectiva, 2013), p. 92.