By: Douglas Gray

As stakeholders and policy makers work on predictions of the direction the Trump Administration’s foreign policy will take, uncertainty regarding Washington’s moves in the Asia-Pacific has mounted. Overtures from the new administration regarding a $54bn increase in the Pentagon’s military budget next year, a ten percent rise to ‘ensure America wins its future wars’, have made allies and adversaries alike uncertain of Washington’s next step. In relation to the South China Sea, signalling from the Trump Administration appears to be indicating a more hawkish and militaristic stance on the dispute, in line with chief strategist Steve Bannon’s public beliefs that war between the two powers is inevitable. However, a militaristic response is short sighted in such a complicated geopolitical contest. By placing the South China Sea disputes in the context of the wider China-US geopolitical contest, this article will identify the shortcomings of solving the disputes with a military-first response. Beijing’s strategy recognises that as China’s sphere of influence grows – enhanced by economic and diplomatic might in the region – it will be possible to recoup relations with regional states after a fundamental status quo change in the South China Sea has occurred. So if Washington hopes to combat Beijing’s adventurism it must effectively bolster and extend its own sphere of influence in turn.

Representing a crucial waypoint in the Indo-Pacific region, the South China Sea is bordered by Brunei, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, and Vietnam. The seemingly marginal sea contains a rich and heavily exploited fishing ground as well as significant oil and gas reserves. And it is not just natural resources that make the South China Sea valuable; Japan, South Korea, and other non-littoral states rely heavily on maritime trade and energy flow through the disputed waters. It is the significance of this major shipping lane, the overlapping sovereignty claims to the Sea’s reefs and increasingly hard-line policies in enforcing such claims that have continuously brought the South China Sea to the fore in regional geopolitics. Maritime disputes in the region focus primarily on the major reefs and rocks scattered across the contested waters, including the Paracel Islands, Pratas Islands, Spratly Islands, and, perhaps most importantly, the Scarborough Shoal. Being subject to a series of overlapping claims by states, the different reefs and their surrounding waters are the centre of a persistent set of legal and territorial disputes, with the largest claim being China’s nine-dash line.

The contemporary disputes are rooted in these early stages of gradual status-quo change over successive decades, with the reinforcement of claims now exacerbating tensions. [1] Beijing’s tactics in the region have been described as the “slow accumulation of small actions, none of which is a casus belli, but which add up over time to a major strategic change,” a tactic Robert Haddick coined ‘salami slicing.’ The gradual acquisition of reefs and features within the South China Sea enabled an increased presence, and a consolidation of territorial claims has been enabled by artificial reef extensions throughout the South China Sea. [2] Extensive infrastructure-building has allowed Beijing to move towards a fundamental shift in the status-quo of the region in their favour, allowing for dominance of the all-important sea lanes and the natural resources below them. The building of airbases and military infrastructure at an unprecedented pace, including reinforcement with surface-to-air missile sites, has changed the nature of the disputes, which have taken on a much more overtly strategic tone. The infrastructural investments, coupled with rapidly accelerating procurements by the Chinese Navy (18 new ships were commissioned in 2016), speaks to a militarisation of the region that is unprecedented in the post-WWII era.

Legally, the international laws governing the disputes are based on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), established as a framework to balance the interest of both coastal and seafaring states. [3] This legal framework drew significant attention on July 12th 2016 when the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) ruled overwhelmingly against Beijing in a legal contest brought on by Manila. In assessing whether or not Beijing had breached its obligations under UNCLOS, the court not only stated that China’s nine-dash line claim had no legal basis but also presented a damning indictment of Beijing’s behaviour throughout the proceedings. However, perhaps unsurprisingly to international law sceptics, the court’s ruling has seemingly had no effect on the current state of the disputes due to the lack of an accompanying enforcement mechanism.

Legally, the international laws governing the disputes are based on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), established as a framework to balance the interest of both coastal and seafaring states. [3] This legal framework drew significant attention on July 12th 2016 when the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) ruled overwhelmingly against Beijing in a legal contest brought on by Manila. In assessing whether or not Beijing had breached its obligations under UNCLOS, the court not only stated that China’s nine-dash line claim had no legal basis but also presented a damning indictment of Beijing’s behaviour throughout the proceedings. However, perhaps unsurprisingly to international law sceptics, the court’s ruling has seemingly had no effect on the current state of the disputes due to the lack of an accompanying enforcement mechanism.

While the United States is in a comparably weak position to challenge the lack of conformity to international laws and norms in Beijing’s island claims, given that it is the only major power not to have ratified UNCLOS, it has cited the violation of ‘customary international law’ in its efforts to counter what it views as Chinese expansionism. Since 2015 Washington has conducted four freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs) through the contested waters to challenge Chinese claims, along with diplomatic efforts. In October 2015, the USS Lassen exercised innocent passage by patrolling within 12 nautical miles of Chinese-controlled Subi Reef. Later on, in January and May 2016 respectively, the USS Curtis Wilbur and the USS William P. Lawrence conducted FONOPs near Triton Island and Fiery Cross Reef – both of which were heavily condemned by Beijing. Most recently, the USS Decatur undertook a FONOP near the Paracel Islands in October 2016, in what was declared to be the first iteration of a ‘more regular operations tempo’ to come.

And it would seem that the tempo has in fact increased. The arrival of a US carrier strike group to the South China Sea on February 18th, including the Nimitz-class USS Carl Vinson and an escorting destroyer, the USS Wayne E. Meyer, represents a significant step up in US military presence in the region. While the carrier has been en route since before Trump’s entry to the oval office, having previously been in Guam and the Philippine Sea, the illustration of power has concerned pundits amid rhetoric that has come from the new administration. Recent comments by US Defence Secretary Jim Mattis during his visit to Tokyo appeared to largely reassert the policy status quo toward the region set by the Obama Administration. Mattis’ public comments that the issue is ‘best solved by diplomats’ were welcomed by Beijing. In private, Mattis has reportedly stated that ‘America would no longer be that tolerant of China’s behaviour in the South China Sea,’ pledging to take a more aggressive stance and increase patrols. The comments reflect a US administration seeking to take a hard line on the issue, consistent with earlier remarks by now-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson at his confirmation hearing, who implied that the US would attempt to blockade China’s access to islands – a contentious claim later moderated by clarifying that this would only apply ‘if a contingency occurs.’

It is based on comments such as these that a continuation down the path of militarisation of the region has been widely tipped as the Trump Administration now articulates its foreign policy. Proponents of a more hawkish stance on the issue are pushing for the Trump Administration to execute a military rebalance to Asia in a more steadfast way than the previous Obama Administration. They argue that the US should look to impose a strategic risk on Beijing’s belligerence in order to reassert dominance. However, while deterring expansionism is necessary, a focus on militarisation is informed by a short-sighted viewpoint of Beijing’s strategy in the region.

As South-east Asian states seek to hedge between the two major powers, cautiously attempting to push Beijing and Washington towards cooperation rather than confrontation, Washington’s hopes of alignment against excessive Chinese claims have been dashed. ASEAN’s continuous claims of unity and harmony are often fragile and hollow. It has adopted a muted line in the wake of the UNCLOS ruling last year, choosing not to speak up about the issue. In a region finding itself increasingly reliant on China’s economic power, individual states’ interests, as well as those of the community as a whole, are shifting. Beijing’s strategy is based on economic leverage and the belief that the region is naturally inclined to fall within its sphere of influence. While assertiveness in the South China Sea has exacerbated disputes with its neighbours, trade dependencies and carefully managed diplomacy have prevented the long-term costs frequently affiliated with such adventurism. The lacklustre reaction to the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s ruling on the territorial disputes is a direct result of Chinese influence and concerns from regional stakeholders regarding the economic and political repercussions of pursuing action on the ruling.

At present, Beijing’s extensive infrastructural investments have not been militarised beyond defensive measures. While the islands have the capacity to host fighter and bomber squadrons, missiles or PLAN vessels, no such militarized actions have yet been taken. Beijing’s stance remains that Xi Jinping’s 2015 promise not to militarise the region has been upheld – and while satellite imagery provides ample evidence to dispute this, the stall in further escalation from Beijing puts American responses on the back foot. The ultimate symbol of this strategy’s success perhaps came last year, during the last FONOP by Washington in October. Chinese state media was able to achieve a significant diplomatic coup by labelling the United States as the belligerents of the South China Sea, a move only made possible by effectively bringing Manila ‘into the fold’, with President Duterte having been in Beijing at the time for conciliatory talks. Former US Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick once urged China to become a responsible stakeholder in the region – but perhaps Beijing being viewed as a responsible stakeholder and provider of economic wellbeing is the biggest threat to US interests.

So if the Trump Administration is to counter Beijing’s adventurism in the South China Sea, a strategy beyond simplistic militarisation of the dispute must be employed. As the American liberal world order is increasingly challenged on the global stage, including Moscow’s actions in Crimea and Beijing’s rejection of the PCA ruling, measures to strengthen it must likewise be maintained. The establishment of the post-WWII, US-centric alliance systems in Europe and Asia, along with the World Bank, IMF and GAT, placed policy makers in Washington in an unprecedented leadership position. While having the biggest economy and an unparalleled military are important for superiority on the world stage, the continuity of American primacy over the last three decades has been built upon a bastion of institutional leadership, both economic and political – something that should not be forgotten. While Washington has had to contribute a disproportionate amount to these institutions and alliances, it is not because policy makers were duped, but because they recognised that the benefits of leadership outweighed the costs. The Bretton Woods system and subsequent dominance of world trade were not fashioned out of altruism, but as a way of advancing the interests of the United States via systemic leadership.

After the Trump administration abandoned the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement – the economic centrepiece of Obama’s rebalance to Asia - without a replacement, doubts were been raised in Asia about the future credibility of US leadership in the region. While the TPP has been a contentious issue, the rationale underpinning the agreement represented an extension of the post-WWII American rules-based order strategy that has underpinned its pre-eminence for decades. Furthermore, Beijing is currently advancing its own institutions that challenge the US leadership - such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. In this context, active retrenchment from international institutions carries enormous costs to Washington. Xi Jinping’s portrayal of Beijing as an alternative leader of globalisation at Davos in January has been widely touted as the seizing of an opportunity to place China in a position to adopt a mantle of leadership as the US recedes. And in Southeast Asia, the formation of the aforementioned Beijing-centred institutions provides the framework for the assumption of economic and trade leadership throughout the region. China is already an indispensable trading partner in most of the Asia-Pacific region and is rapidly placing itself at the heart of a new set of institutions to provide the foundation for extending a sphere of influence which is in parts already there.

So if the new administration in Washington hopes to combat Beijing’s adventurism in the South China Sea, it must recognise both Beijing’s wider strategy and the structural factors of America’s own pre-eminence before intensifying a militaristic response. The absence of war that has been sustained in the Western Pacific over the last four decades has been fundamental to the political stabilisation and economic development of the region – and it is in no state’s interests for this to end. A return to the competitive cat-and-mouse military confrontations of the Cold War era is fundamentally short-sighted and fails to recognise the wider geopolitical contest between Beijing and Washington. So as Beijing seeks to extend its sphere of influence and deter continued American pre-eminence in the region, the Trump administration must bolster its structural influence, otherwise, Washington will increasingly find itself disadvantaged.

So how can the Trump Administration undertake this task? Most importantly, it must be appreciated that the expansion of US access to Asian economies amid the much touted Asian-century was not only about economic leverage, but also about consolidating a US sphere of leadership and influence which has staggered as China grows. While the military must play an important part within a reinforcement of US interests in the region, it should be harnessed to further reinforce structural leadership. For instance, a return to discussions to establish an Indo-Pacific Quad, a hypothetical military alliance United States, India, Japan, and Australia, could both reinforce influence and establish a US-centric institution with the authority to weather Chinese claims of American belligerence. Likewise, active engagement with ASEAN states, both individually and collectively, must be maintained, in order to ensure the US presence in the region is continually recognised. In order to counter Beijing’s economic weight, an alternative to the TPP must be sought, otherwise Chinese will increasingly harness the ability to rewrite the US rules of trade in the region. Beijing’s strategy is based on an appreciation that its own sphere of influence is growing with time, so in order to counter this, the Trump Administration must reassure the region as a whole that they are there to stay.

Douglas Gray is a Masters student at Kings College London in the War Studies Department, studying Intelligence and International Security. Previously, he completed his honours degree at Victoria University Wellington in New Zealand, majoring in international relations and political science. His special research interests are information warfare, intelligence sharing and competition in the Indo-Pacific.

Endnotes

[1] The current round of tensions were sparked after a tense standoff between Beijing and Manila over the Scarborough Shoal in 2008; eventually leading to Beijing’s de facto control of the outcrop in 2012. Later, in 2014, another standoff occurred between Beijing and Hanoi over drilling operations by a Chinese state-owned oil company 17 nautical miles from Triton Island, eventually leading to the sinking of a Vietnamese fishing boat and anti-Chinese riots in Vietnam.

[2] While Beijing is notably not the only state reclaiming land in the South China Sea, with similar activities being undertaken by Taiwan, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia, they have certainly done so further and faster than any others.

[3] Ratified by nearly all coastal states in the disputes, UNCLOS establishes an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) within 200 nautical miles of coastal waters while also guaranteeing passage rights for naval vessels through these zones.

Image 1 source: https://qz.com/763161/it-is-time-to-rename-the-south-china-sea/

Image 2&3 source: https://amti.csis.org/fiery-cross-reef/

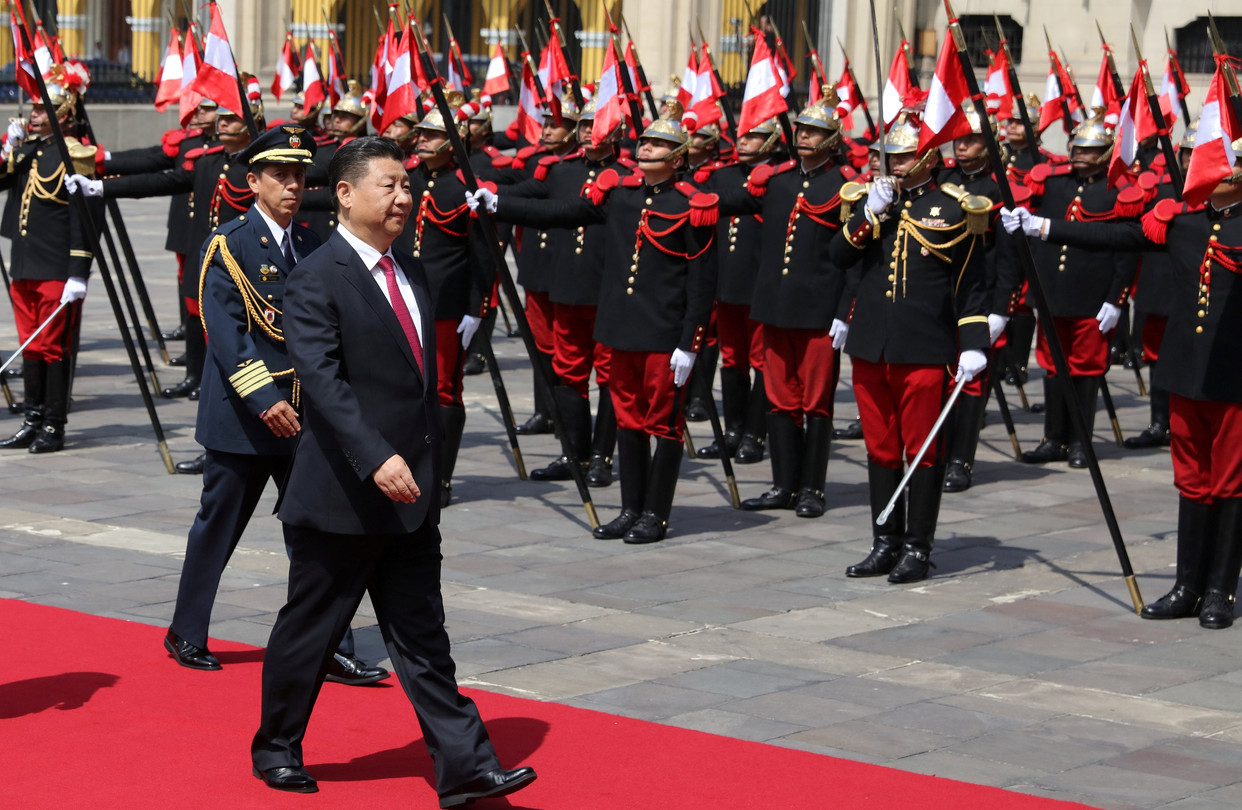

Image 5 source: https://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/BN-RO104_0109da_GR_20170109164947.jpg

Divorces are messy. They separate families by turning parents against each other as they negotiate over their assets and determine child custody rights. Furthermore, children often have to make uneasy decisions and can find themselves pitted against one of their parents while siding with the other. Such actions resemble the British attempt to divorce from the European Union (EU) following the Brexit referendum. Commentators have rushed to consider the political and economic implications of the decision while shying away from potential security and defence effects. Economic strains imposed by Brexit and the transition-related hurdles stood up by the EU will further challenge Britain’s military status and defence role in Europe and beyond.

Divorces are messy. They separate families by turning parents against each other as they negotiate over their assets and determine child custody rights. Furthermore, children often have to make uneasy decisions and can find themselves pitted against one of their parents while siding with the other. Such actions resemble the British attempt to divorce from the European Union (EU) following the Brexit referendum. Commentators have rushed to consider the political and economic implications of the decision while shying away from potential security and defence effects. Economic strains imposed by Brexit and the transition-related hurdles stood up by the EU will further challenge Britain’s military status and defence role in Europe and beyond.

The United Kingdom has remained largely unaffected by the refugee crisis which has rocked the Middle East and much of Europe over the last few years. As the UK has one of Western Europe’s most stringent refugee policies in place already, the

The United Kingdom has remained largely unaffected by the refugee crisis which has rocked the Middle East and much of Europe over the last few years. As the UK has one of Western Europe’s most stringent refugee policies in place already, the