By Axel Dessein

6 March 2019

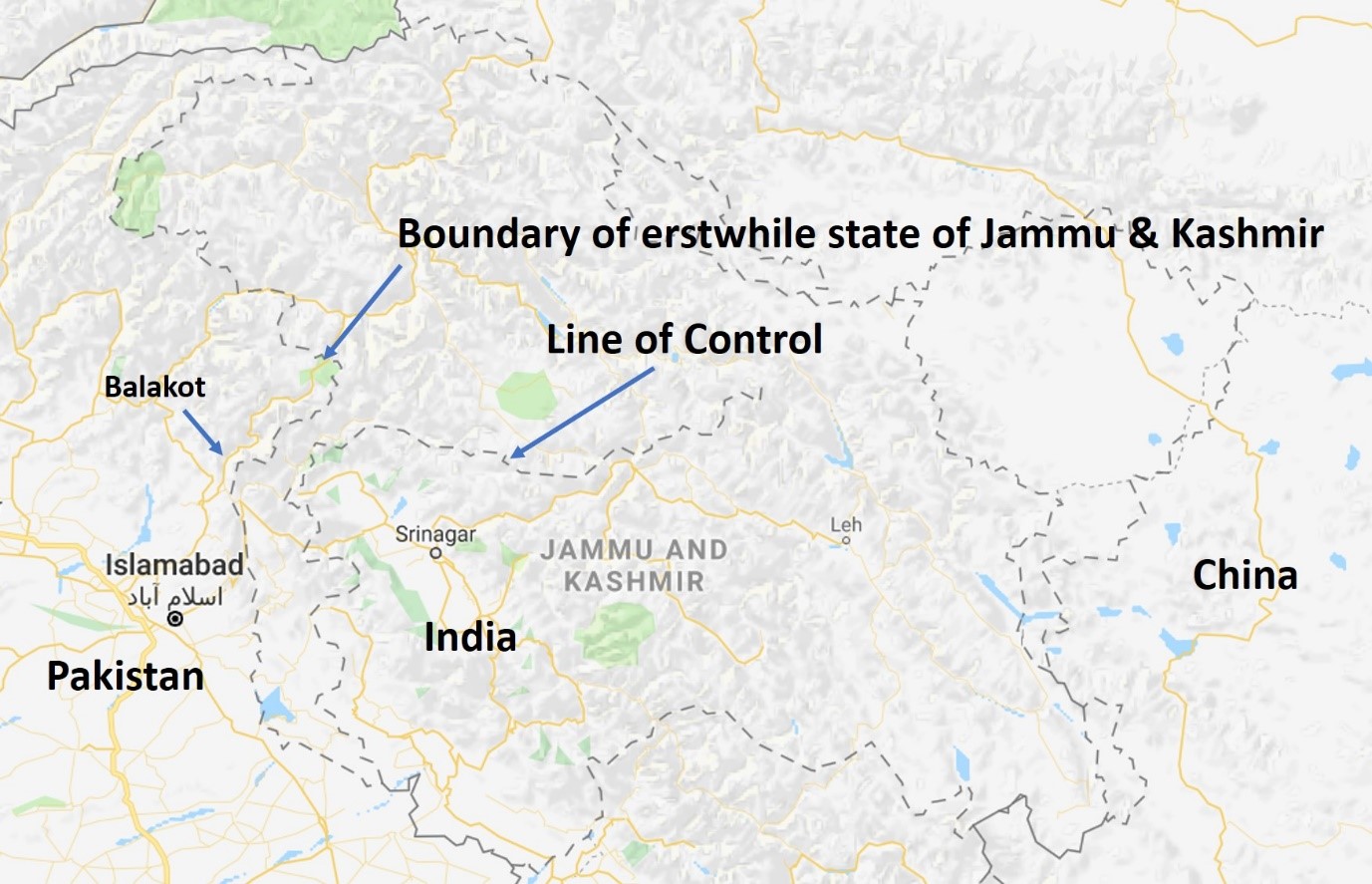

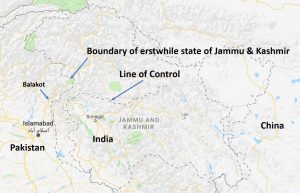

Next to the ongoing U.S.-China trade war and the premature ending of Donald Trump’s meeting with North Korea’s Kim Jong-un in Vietnam’s Hanoi, it seems somewhat odd that the risk of war between the two nuclear-armed countries India and Pakistan was only the third newsworthy item last week. In retaliation of a suicide bombing against Indian paramilitary police in the Pulwana district of Jammu and Kashmir earlier last month, Mirage 2000 planes of the country’s air force on February 26 bombed a presumed stronghold of Jaish-e-Mohammed terrorists in the town of Balakot, located inside Pakistani territory. In response, the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) shot down two Indian Air Force (IAF) MiG-21 fighter jets on February 28, leading to the arrest of Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman. While the captured pilot was released on March 1 as a peace gesture by Pakistan’s prime minister Imran Khan, the fog of war has not yet receded.

The other fighter pilot presumably went down in Indian-controlled Kashmir, according to Major General Asif Ghafoor. There are also reports which indicate that the IAF shot down an F-16 of the PAF, but proof remains meagre at best. The suicide bombing, the deadliest since the beginning of the insurgency in 1989, set into motion a simmering spiral of events, which seemed to carry through over the weekend, with shelling resuming across the Line of Control (LoC) on Friday but declining in intensity later on. In this article, I aim to first focus on the crisis that took place, adding some more information to two earlier pieces. Next, I bring into account the role of China, Pakistan and India’s big neighbour to the East.

Don’t get MAD

Last week’s hostilities were yet another violent iteration of the countries’ territorial claims over the region of Jammu and Kashmir. In earlier articles published on the Strife blog, Kamaldeep Singh Sandhu and Saawani Raje graciously analysed the risk of nuclear war between the two countries according to an escalation ladder (or pyramid) with its three rungs of sub-conventional, conventional and nuclear response. Somewhat counterintuitively at first sight, the authors noted that the nuclear capabilities of both Pakistan and India in fact increase the stability in the region. Little wonder, since a nuclear exchange between these countries would be disastrous. As Karthika Sasikumar of San Jose State University notes, even a single strike on a big city, would lead directly to nuclear midnight, wreaking havoc on the socio-economic and political systems of both countries and the wider region. It is clear, nuclear war is MAD, as it would almost directly lead to mutually-assured destruction of Pakistan and India.

Nevertheless, it is clear that India has upped the ante by employing conventional firepower in the contested region of Jammu and Kashmir. The Indian Express even calls it a “milestone in India’s retaliatory response to terror.” The nature and scale of which was something like seen in Afghanistan, Iraq or Syria, as one senior officer is quoted as saying. Following the Pulwana attack, India’s prime minister Narendra Modi noted Pakistan’s involvement and publicly gave clearance to the country’s military brass to “decide the time and place of response.” However, details of what happened on the operational level remain scarce. Uncertainty is equally high about the success of the IAF mission. Indeed, satellite imagery is raising doubts about whether the IAF’s Israeli-made SPICE-2000 precision-guided munitions actually hit the Madrassa Taleem al-Quran, a JeM religious school and the specific number of insurgent casualties. It is also unclear whether the IAF actually crossed the LoC or whether the SPICE missiles were launched from the Indian side of the line.

Reports are also unclear about whether the PAF scrambled F-16 or JF-17 fighter jets in response to the presumed IAF incursion of Pakistan’s air space. A deployment of the U.S.-made F-16s in this scenario for example would be an infringement on the end-user agreement, now said to be under investigation by the U.S. State Department. In contrast, the JF-17 is a product of a joint-venture between the Pakistan Aeronautical Complex (PAC) and the Chengdu Aircraft Corporation (CAC) of China. A further display of the ties between the countries whom define their relationship as an “all-weather strategic cooperative partnership,” was also visible shortly after the escalation by the IAF.

The neighbour to the East

With no real end in sight, Pakistan’s foreign minister Shah Mehmood Qureshi on February 27 called on his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi for China to play a “constructive role in easing the tensions.” As published on Sina News, Wang expressed his deep concern about the tensions between Pakistan and India, briefing Qureshi on the Chinese efforts to persuade and facilitate talks and reiterating the hope that both countries will exercise restraint and fulfil their commitment to prevent the escalation of the situation. The statement followed an earlier Chinese acknowledgement at the U.N. Security Council of the “heinous and cowardly suicide bombing” by JeM. Indeed, China’s Foreign Ministry repeated its condemnation of any form of terrorism and called upon the countries involved to cooperate in preserving regional peace and stability.

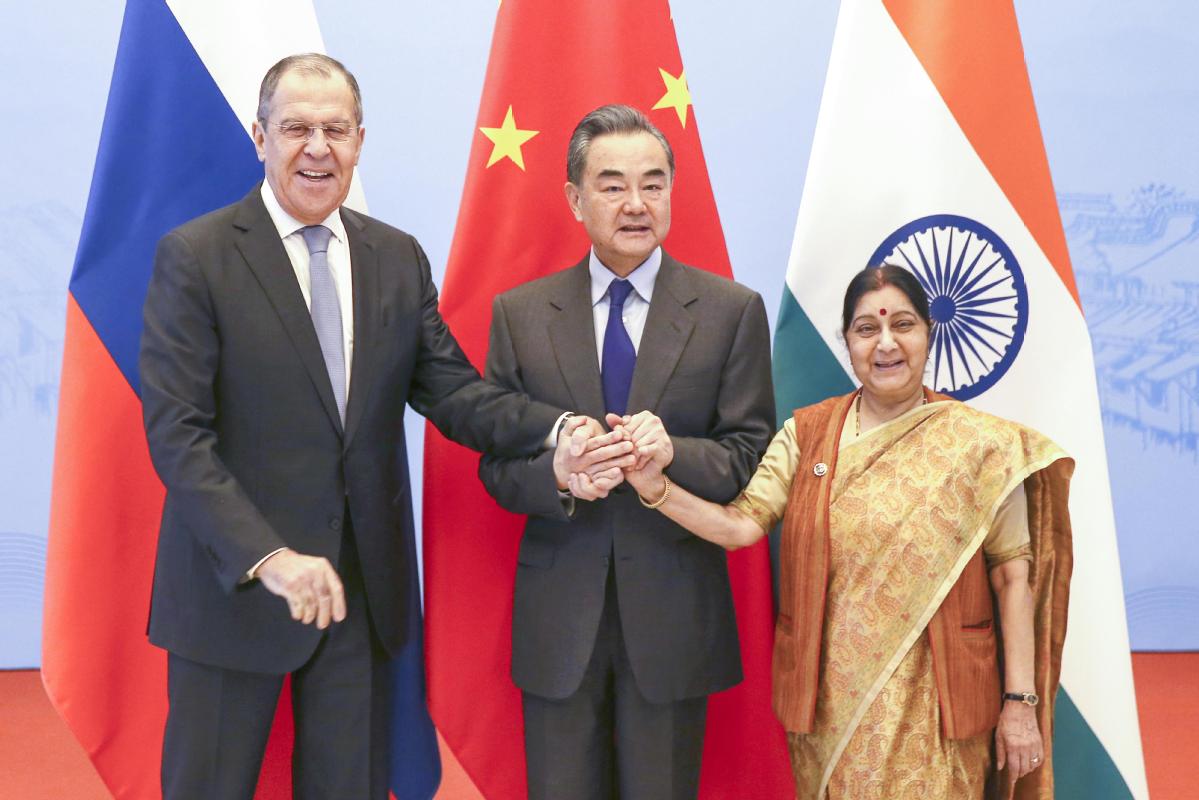

Interestingly, it was right in the middle of the Kashmir crisis that the 16th trilateral meeting between Russia, India and China took place on February 27 in Yueqing, China’s Zhejiang province. At this meeting, the country’s respective foreign ministers Sergei Lavrov, Sushma Swaraj and Wang Yi issued a joint statement condemning “terrorism in all its forms and manifestation” and called for the strengthening of the U.N.-led counter-terrorism efforts. Here, it is interesting to draw attention to the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, a multilateral security alliance which Pakistan and India both joined as a full member during the June 2017 summit in Astana, Kazakhstan. With China and Russia leading this organisation’s struggle against terrorism, these countries could act as important mediators in the tensions between Pakistan and India.

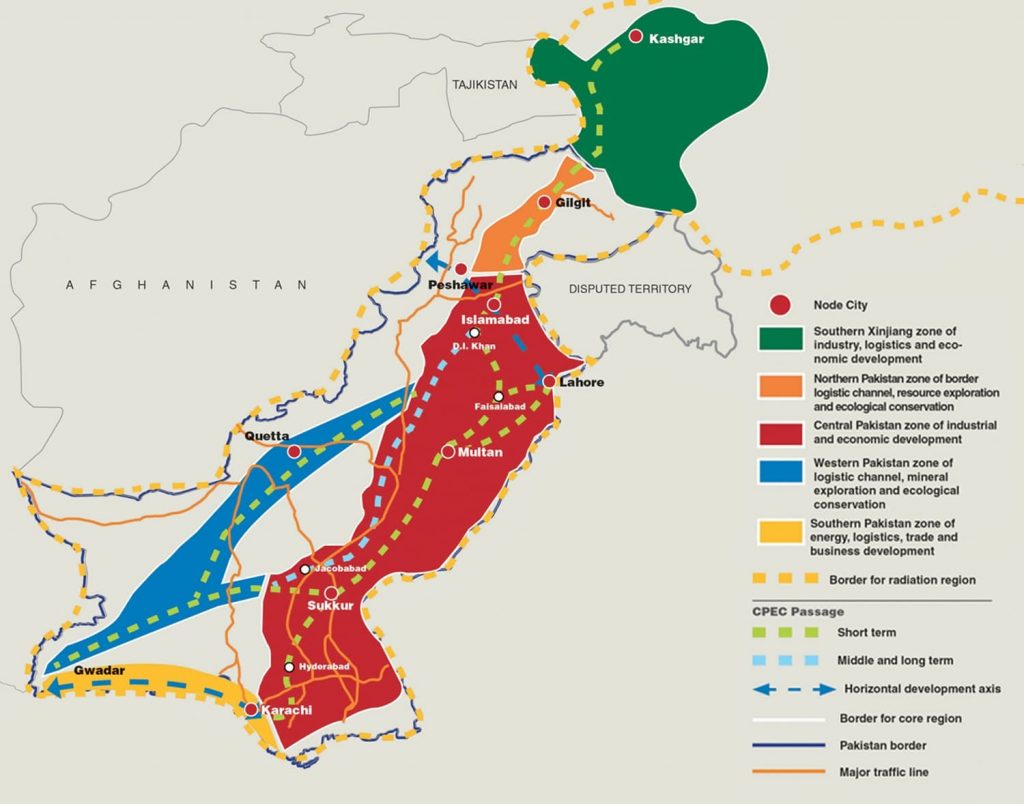

However, China itself also has territorial disputes with India, tensions which undoubtedly complicate the manner in which China can play a mediating role. Most important among these disputes is the region of Aksai Chin, part of the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir, and the northern Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh. But a small corridor between China, India and Bhutan is also cause for concern. To halt Chinese road-building, the area known as the Chicken’s Neck was the main stage of a long-lasting standoff at the Doklam plateau in the Summer of 2017. While not disputed territorially, it was the proximity of Chinese troops and their intrusion into Bhutan’s Doklam that raised Indian suspicion and ultimately triggered a reaction. In those towering heights of the Himalayas, Indian and Chinese troops even engaged in a stone-fight. To complicate matters even more, there is also the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, the flagship project of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which aims to connect the Chinese north-western city Kashgar with the Pakistani port of Gwadar. As such, the CPEC can be traced right through many of disputed regions within Pakistan.

In an article for The Diplomat, Vasabjit Banerjee of Mississippi State University and Prashant Hosur Suhas of Eastern Connecticut State University offer important analysis on the Indian capabilities to handle a war with Pakistan or even a two-front war with Pakistan and China. While that may be so, the author similarly points to the fact that China’s military is primarily geared towards the U.S. and its allies, such as Japan. Rather than focusing on the possibility of nuclear war, one could do well by considering more broadly the many escalatory actions that can take place below the nuclear threshold. Indeed, when considering the close relationship between China and Pakistan, one can beg the question whether China may ultimately employ its relationship with Pakistan to add increasingly more pressure on India, in an area already rife with terrorist factions opposed to the Indian government. Somewhat contradictory, there is also the question of China’s expanding role in counter-terrorism and peace-keeping in Central Asia and beyond. Indeed, Gerry Shih of the Washington Post recently reported about Chinese uniformed presence in Tajikistan, near Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor. The question one can ask here is whether China’s political-territorial interests would prevail over the preservation of stability in the region itself.

Conclusion

While the meeting between Russia, India and China went largely unnoticed, it is an interesting development showcasing China’s commitment in creating a more secure region. In light of the deadly attack in Pulwana, the country strictly condemned the terrorists while calling on Pakistan and India to de-escalate the tensions. At the same time, China has many stakes of its own in the region. With the CPEC running right through Pakistan, it could very well be that the country would help its “all-weather” partner Pakistan secure its claims against India, the country with which China has several territorial disputes itself. Nevertheless, this episode has shown the potential role of China as a mediator between states. Let’s watch this space.

Axel Dessein is a doctoral candidate at King’s College London and a Senior Editor at Strife. His research focuses on interpreting the rise of China. Axel completed his BA and MA in Oriental Languages and Cultures at Ghent University in Belgium. You can follow him on Twitter @AxelDessein.

Image sources:

http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201902/28/WS5c771b3ca3106c65c34ebd56.html

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/02/indian-air-raid-site-casualties-mysterious-madrassa-190227183058957.html

https://www.dawn.com/news/1371720