By Nesma El Shazly

I was not allowed to leave the house throughout the first week of the revolution. Although my parents wholeheartedly endorsed the revolution, they feared for my life and would not let me join the protests. For this reason I spent that week documenting the events as they unfolded from my own home. The Egyptian people were revolting against sixty years of military rule, calling for three demands: bread, freedom and social justice. For eighteen consecutive days, protesters were engaged in face-to-face confrontations with President Mubarak’s brutal central security forces. Revolutionaries peacefully faced live ammunition, rubber bullets, tear gas, kidnappings and detainment with complete fearlessness.

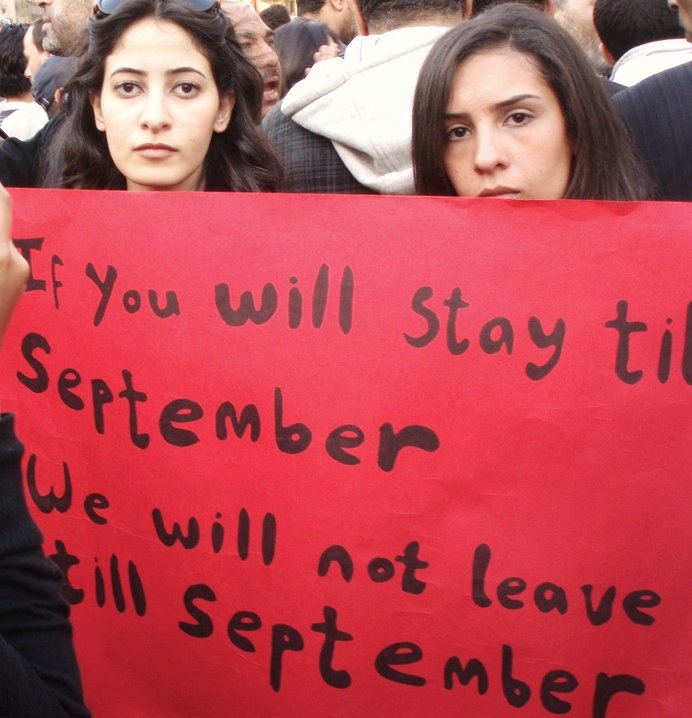

After watching the horrifying brutality with which protesters were met on The Friday of Anger (28 January), I decided that enough was enough. I could not sit at home helplessly watching my people die. I frantically called up all my friends to see who was willing to march to Tahrir Square with me. Needless to say most of my male friends tried to discourage me out of concern for my safety. I was one of many women facing difficulty in taking to the streets and so, my friends and I, all women, decided to join the ‘Million Man March’ on 1 February.

As I walked down the stairs carrying the banner that I had spent the whole night making, my mother followed me, tightly gripping my hoodie, trying to pull me back. My brother drove me to my friend’s house, where we had all planned to meet. That morning came to be a turning point in my life. As we were about to leave to Tahrir, my best friend called me from the airport to tell me that she and her husband were leaving for the U.S for the safety of their 2 year-old child. I experienced a mixture of conflicting emotions. I felt content that I was doing the right thing, excited that I was going to be a part of making history, apprehension of the risks I was about to take and sorrow that I could not even bid my best friend farewell.

There were three phases to our day: comedy, terror and euphoria. The first phase took place on the underground train. As we purchased our tickets the vendor looked at us with pride and said “May God be with you,” while a man standing behind us in line looked at us in disgust and told his wife that we were probably drug addicts. As we boarded the train, an old man selling copies of the Quran followed us on and tried to convince us that we should buy a copy and read it before we go to Tahrir and die. The adverse reactions we received throughout our journey put us in hysterics.

We experienced the second phase - terror - as we got off the train in downtown Cairo. We marched through the streets towards the Square alongside several other small groups. Mubarak supporters were surrounding the Square yelling out foul words at all the revolutionaries. An older woman followed me and grabbed my arm asking me where I was going. I looked her straight in the eye and said, “I’m going to Tahrir.” She tightened her grip on my arm and started hitting me and shouting out, “You are going to ruin this country! You are going to turn Egypt into Iraq!” My friends eventually realized that I had been held back and ran to my aid. It was only at this point that we realized the extent of danger we were subjecting ourselves to. We resumed our journey quietly.

As we got closer to the Square we started hearing the enthusiastic chants of the protesters, “Al sha’ab yoreed isqaat al nizam!” (The people demand the fall of the regime!) Surges of revolutionary spirit and energy shot into us, abolishing our fear and wiping away thoughts of our encounter with Mubarak supporters. I have never felt as safe as I did that day in the Square. We were all brothers and sisters uniting for one common goal. People welcomed us as we marched in, handing us water and fruit. Nobody looked at us. No man tried to harass us. Everyone there truly believed in the cause. They knew that this was a matter of life or death.

While the world classifies the events of 25 January as a revolution, most revolutionaries have a contrary view. We ousted one brutal figurehead, and that in itself is a tremendous accomplishment. But we have yet to dissolve the ruthless military regime that has ruled our country for 60 years. The Egyptian public was manipulated into believing that the military supported our revolution. But their assumption of power following the ousting of Mubarak suggests otherwise. It seems more likely, in my eyes, that the military sought to reinstate their power, which had seen a downturn during Mubarak’s later years. Throughout that period, Mubarak shifted his focus towards the business elite, bringing prominent businessmen into the political sphere.

During November 2011, the public was voting in the parliamentary elections that the military was administering. Concurrently, protesters were being attacked and killed by central security forces in the Mohamed Mahmoud clashes. Not only were we seeing the military gradually replace central security forces, we were also seeing protesters being unlawfully detained and tried in military prisons and courts. Furthermore, we had yet to see the last of Omar Suleiman and Ahmed Shafiq, who later sought to run for presidency. Omar Suleiman, a leading figure of Egypt’s inhumane intelligence system, renowned for his direct implication in the CIA’s callous rendition programme, took on the role of Vice President on 29 January. Suleiman later sought to run for the 2012 presidential elections. However, he failed to garner enough support in the initial stages of the race. Ahmed Shafiq, a military-backed figurehead that turned his back on the revolution through his assumption of the position of Prime Minister on 31 January, also sought to enter the race. However, unlike Suleiman, Shafiq somehow managed to garner widespread support. His support base mainly derived from ardent anti-revolutionary supporters of the Mubarak regime and the military, as well as liberals who feared the growing dominance of the Muslim Brotherhood in the political sphere. The fact that Shafiq was even able to run for president, let alone make it to the final round of the elections, shows that the revolution is far from over

—

Nesma El Shazly was born and raised in the UK. She moved to Egypt in 2007 to study at the American University in Cairo. On 1 Feb 2011, she took to the streets in protest and she has been a participant of the Egyptian Revolution ever since.

COMING SOON ON STRIFE: ‘The Lost Revolution’, by Lamya Hussein Marafi, assessing the remaining challenges for Egypt’s revolution.