Editor’s Note: The author of this article has requested anonymity. After review by Strife’s Managing Board, this article is being published anonymously in accordance with our documented Publication Ethics.

The Machiavellian question of whether it is better for the prince to be loved or feared can be applied to Myanmar’s military – the Tatmadaw. Could the Tatmadaw ever be loved? To most outsiders, it is a brutal, unaccountable and corrupt institution. And this may indeed be the case. A country’s military should be professional and politically neutral, with the sole purpose of defending the sovereign against foreign invaders. They should never turn their guns on their own people nor govern the country in any capacity except security-related matters.

However, Myanmar is far from an ideal republic. There is such a huge gap between the Tatmadaw’s actual behaviour and how it ought to behave that it is pointless judging it on moral grounds. The more insightful question is why, despite numerous massive popular uprisings since the Tatmadaw’s inception, haven’t we seen any significant loyalty shifts within the institution? The Tatmadaw has survived the decades-long dictatorships of General Ne Win and Senior General Than Shwe without showing any signs of major internal loyalty shifts.

The past six decades of mostly quasi-military rule have not been short of mass popular uprisings either. There were the University of Rangoon students protesting against military rule in 1962, the waves of protests from economic grievances in the 1970s, protest over U Thant’s burial in 1974, the infamous 8888 uprising in 1988, the Saffron Revolution in 2007 and the current crisis. All these movements were brutally crushed yet failed to cause any significant loyalty shifts within the Tatmadaw. Would another potential dictatorship, led by Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, be any different this time?

Continual conflict on all sides

The Tatmadaw is understandably far more paranoid than other militaries. Since its founding, the Tatmadaw has fought the British and the Japanese for independence, the Burmese Communist Party, a huge number of ethnic insurgencies, the Kuomintang, and drug lords, all while attempting to consolidate the state after independence. In 1949, just a year after independence and following the rebellion of the Burmese communists and the Karen, large swathes of countryside and suburbs of the then-capital Rangoon were in the hands of either the Burmese Communist Party or Karen rebels. It is from this position of weakness that the Tatmadaw reasserted territorial control over the country.

The Tatmadaw have fought non-stop bloody wars on multiple fronts, in malaria-infested jungles and difficult terrain, against a multitude of rebellions and adversaries, some with superior resources and weapons. It is in this context of continual uprisings that the absence of internal loyalty shifts and the brutal, uncompromisable Tatmadaw must be understood. Whatever internal divisions exist within it, when faced with any force threatening to jeopardise its mission of preventing the disintegration of the Myanmar union, the Tatmadaw closes ranks and faces the common enemy. Regardless of which dictator is in charge, the Tatmadaw’s history is one of counter-insurgencies preventing the disintegration of the union.

The means of nation-building and counter-insurgency are inherently conflicting, but the ends can be surprisingly in harmony. Counter-insurgency serves to preserve sovereignty and territorial integrity – prerequisites for state-building. As battle-hardened soldiers, the Tatmadaw will sacrifice most things over territorial control and integrity. Their baptism in the harsh realities of the battlefields against a multitude of adversaries in difficult environments taught them that fear is more reliable than love. As Machiavelli put it, love is fickle while fear is constant.

Nevertheless, the Tatmadaw must understand that nation-building is not simply a counter-insurgency project. Winning hearts and minds is as important as their tried and trusted ‘four-cuts’ or scorched-earth strategies.

Wasted opportunity

It is a great pity that the Tatmadaw missed the opportunity to be both feared and loved at the same time, respected rather than loathed by the majority today. A beloved yet feared Tatmadaw could have served both counter-insurgency and nation-building objectives. Aung San Suu Kyi held the key to this. She will go down in history as an extraordinary lady, a once-in-a-generation figure. She has natural charm, charisma and eloquence, and readily elicits virtually unconditional popular support, regardless of her government’s performance. How much of her popularity stems from her persona, her struggle against the Tatmadaw or the people’s deep dislike of the Tatmadaw is irrelevant. What is relevant is that her popularity extends across ethnic boundaries, except for the Arakanese. This is critical for a country such as Myanmar, where state-building has been challenged from the start by deep ethnolinguistic cleavages and multiple simultaneous, militarised and ethnic-based self-determination claims. Any meaningful portion of ethnic minorities’ love for Aung San Suu Kyi, paired with the Tatmadaw’s military might, could have been a perfect match. Their combined powers of seduction and coercion, love and fear, could have been harnessed towards the dual projects of state-building and counter-insurgency, gaining legitimacy from meaningful support of ethnic minorities.

There is nothing fundamentally incompatible between Aung San Suu Kyi and the Tatmadaw that would have doomed their cooperation from the start. Ironically, they share a similar Burmese Buddhist ethnonationalist state view for Myanmar and an authoritarian hands-on management persona. Their inability to work together stems rather from egoistic factors. Why ego is the greatest enemy to the peace process in Myanmar deserves a detailed discussion. But Myanmar now has to deal with the more pressing issue of the increasingly violent resistance.

The strategic advantage of non-violence

People understandably were aggrieved when they felt the 2020 elections were stolen from them. Being emotional and angry are natural reactions in such circumstances. But fighting violence with violence gives the weaker side nothing to gain but emotional venting and, in extreme circumstances, martyrdom, while more innocent people die. What good comes from taking the violent resistance path if it means to play the martyr, gain public sympathy, and in the process, the young lose their chance to outlive the generals they so despise and be the change themselves in years to come?

This does not mean that the seemingly weak have no way to win against the strong and get the results they want.

Aung San Suu Kyi could single-handedly take on the Tatmadaw in a strategic, non-violent manner. Her non-violent struggle for democracy from the 1990s to the 2000s ultimately led to the Tatmadaw’s voluntary democratic transition in 2011 after two decades of junta rule. This gave rise to the most prosperous period since independence.

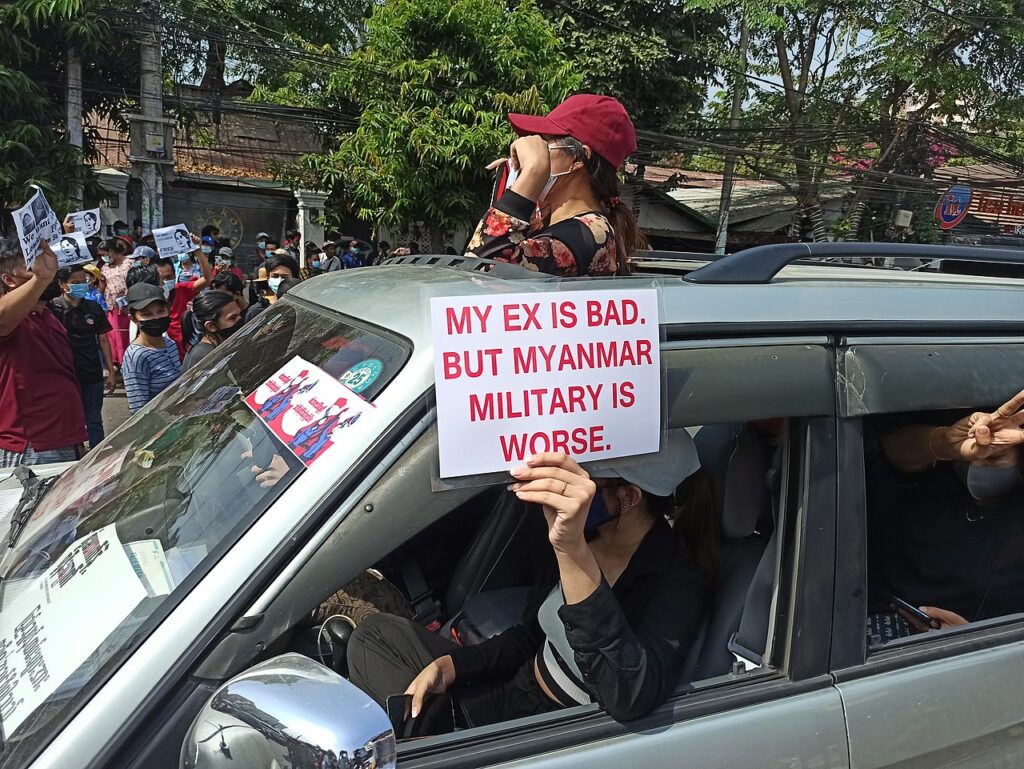

Violence is often condoned only as a last resort in a desperate situation; a necessary evil as a means to an end. However, the idea of violence as an effective way to win concessions from a repressive regime does not stand up to research. Unless a genocide is occurring, non-violence almost always has a strategic advantage over violent resistance. The ethical and security barriers to resistance participation are always lower for non-violent resistance than for insurgencies or terror tactics. Those engaging in non-violent movements are more likely to gain sympathy and credibility from potential local and international partners or supporters and, more importantly, from the ruling elites. The sympathy and credibility earned from a non-violent struggle create loyalty shifts within security forces that are better than violent resistance, which would create an ‘us-against-them’ bunker mentality in an already paranoid, disliked and isolated Tatmadaw.

Studies have shown that non-violent resistance campaigns are much more effective than violent ones at achieving their objectives. Chenoweth and Stephan’s critically acclaimed research on non-violent civil resistance uncovered exactly that. They found that countries in which there were non-violent campaigns were about ten times more likely to transition to democracies within five years, compared to countries in which there were violent campaigns – whether the campaigns succeeded or failed. Even when non-violent campaigning appears to fail, there is increased potential for democracy over time. This is not the case for failed insurgencies. Transitions that occur in the wake of successful non-violent resistance movements create more durable, internally peaceful democracies than those provoked by violent insurgencies. On the other hand, when violent insurgencies succeed, the country is far less likely to become democratic and more likely to return to civil war.

Despite how non-violent resistance may appear to be ineffective in a complex country such as Myanmar, it still has to be chosen because it is more effective than violence in eventually getting results. The International Center on Nonviolent Conflict provides Burmese translated online resources illustrating such non-violent resistance methods.

On the brink of disaster

One may argue that Myanmar has already been in violent conflict for decades and any additional violence would make no difference. This argument is dangerous because Myanmar has all the hallmarks of a conflict trap of genocidal proportions, with humanitarian consequences rivalling any crisis in history. One just has to look at its natural resources and drug production to fuel conflicts, its high numbers of ethnic armed groups, the ethnic and religious frictions, and the hilly and mountainous terrain conducive to a war of attrition. Add to that Myanmar’s geopolitical location with its potential to become a battlefield for proxy wars of the world and regional superpowers, weak state institutions, historical tendencies towards violence, poverty, and endemic corruption. Even if the increasingly violent resistance were to cause such damage to the Tatmadaw that confidence was shaken among the ranks and a significant split occurred, the resulting power vacuum would lead to a full-blown civil war. The ethnic armed groups would likely be drawn into the conflict from the highlands down the Irrawaddy valley, with their different alliances and agendas, with every person for themselves, adding to the numerous ongoing humanitarian crises.

Non-violence – the only viable option

Violent resistance provokes overreaction from the Tatmadaw, resulting in more grievances and loss of lives and thus more overreaction in return. History teaches us countless lessons of violence begetting violence. Therefore, one should ask if a military solution could ever be appropriate for not only the ongoing anti-regime movement but also the endless ethnic conflict? Successful insurgencies or guerrilla campaigns mostly rely on external sponsors and ultimately winning the war of attrition. Any support would have to come from bordering countries, and it is unlikely that China, Bangladesh, India, Laos or Thailand would support a violent campaign in Myanmar.

There is the option to continue the war of attrition, but as Sun Tzu said in “The Art of War”, no state has benefited from prolonged warfare, and victory without fighting is the epitome of military strategy. Non-violent resistance campaigns are more effective in achieving results, and once they have succeeded, are more likely to establish democratic regimes with a lower probability of a relapse into civil war. Myanmar has suffered enough from a never-ending war of attrition since 1949 and the only path towards quality peace is non-violence.