by Farley Sweatman

Source: Paul Kagame

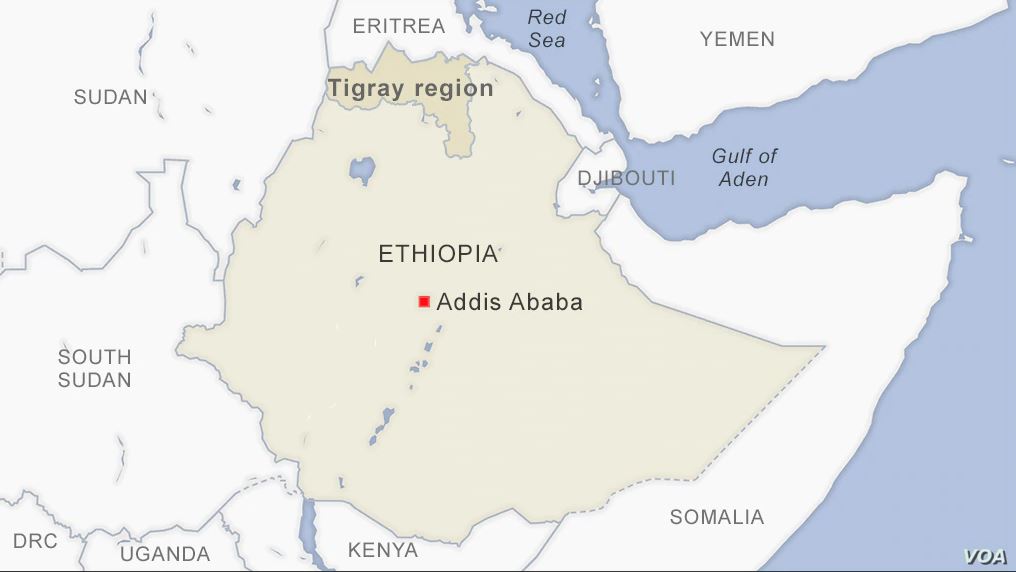

Armed clashes continue across Ethiopia’s Tigray region as Ethiopian National Defense Forces (ENDF) battle fighters loyal to the Tigray People Liberation Front (TPLF). Despite taking effective control of Mekelle, Tigray’s regional capital, in the initial offensive, ENDF troops now face the possibility of a protracted insurgency, with TPLF leaders vowing to fight on in the region’s mountainous interior. More concerning still is that the conflict has taken on an ethnically driven dimension with reports of ethnic profiling by Ethiopia’s federal government against the Tigrayan population. Unless quickly resolved, the crisis threatens to reverse any recent gains made by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s administration towards promoting a shared sense of unity and identity (or Ethiopiawinet) that transcends ethnic lines.

The ramifications of this conflict are two-fold. Internally, the sectarian aspect risks spreading ethnic tensions to other parts of Ethiopia, thereby unravelling the thin blanket of ethno-federalism that has held the country together. Externally, regional rivals Egypt and Sudan may exploit this unrest to derail the contentious Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), which could escalate the violence and prompt an international crisis.

Ethiopiawinet and the beginnings of a renaissance

Ethiopia is rife with potential. While landlocked, Ethiopia has one of the largest freshwater reserves in Africa with over a dozen major rivers flowing out of its highlands. Control of these crucial water basins grants Ethiopia strategic leverage over all of its riparian neighbours. Ethiopia is also Africa’s second most populous country and is the fastest growing economy in the region, experiencing high, broad-based economic growth that has averaged 9.8 per cent annually over the last decade.

Despite these advantages, Ethiopia faces longstanding issues relating to its delicate ethnic framework. The mosaic of ethnicities comprising the Ethiopian space is a serious obstacle for any centralization effort by the central government. After the collapse of the unitary Derg regime in 1991, the victorious Ethiopian People Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) established the current ethno-federalist system, which divided the country into several regions along ethno-linguistic lines. Each of these regions has its own local government, and more importantly, its own security forces.

This new system was defined by widespread corruption, through which the TPLF held disproportionate military and political influence over the other parties in the EPRDF. The ascension of Abiy Ahmed to power in 2018 marked a drastic shift from this trend. Half Oromo and half Amhara (Ethiopia’s two largest ethnic groups), Abiy is a serious reformer who freed thousands of political prisoners, cracked down on corruption, and reached an historical agreement with Eritrea to formally end their long border conflict. Abiy also merged the disparate parties of the EPRDF into a single Prosperity Party (PP). These efforts at replacing the ethno-federalist system with a unitary state are backed by inclusive rhetoric alluding to the concept of Ethiopiawinet or “Ethiopianness” that supersedes ethnic divisions.

Sectarian undertones

The discrepancies between this promised unitary vision and its actual implementation serves as the focal point for the current Tigray conflict. Backed by a predominately Amhara political elite, Abi’s centralising reforms work to marginalise Tigray influence – politically and culturally. The ethnic asymmetry of this supposedly inclusive unitary narrative is illustrated in Abiy’s nuanced messages to the Oromos and Tigrayans. Abiy declared that the “Oromo struggle is the Ethiopian struggle,” while in Tigray he contended that “ethnic differences should be recognized and respected, however, we should not allow them to be hardened to the extent of destroying our common national story.”

Source: Peter Fitzgerald

These ethnic differences permeate the current conflict. Abiy enjoys popular Amhara support with thousands of Amhara militiamen fighting alongside federal forces in Tigray. Meanwhile, scores of Amhara civilians were massacred in Mai Kadra in western Tigray, possibly in response by the TPLF. Abiy’s offensive is largely directed against the TPLF political-military establishment, but increasingly, allegations of ethnic profiling against the Tigrayan population surface – both in Tigray and elsewhere in the country. Tigrayans in the national capital, Addis Ababa, have been harassed and those working in security or civil serves been told not to come to work.

This sectarianism has serious implications which threaten the territorial integrity of Ethiopia. If the conflict is directed against the general Tigrayan population as opposed to a defined political-military entity, there can be no immediate resolution. Failing to quickly resolve this crisis struggle may reinvigorate latent secessionist movements elsewhere in Ethiopia. The Southern Nations region of Ethiopia, for instance, is teeming with nationalist factions. Also, Tigrayan unrest may trigger ethnic Somali irridentist claims in the Ogaden region. If these groups reject Abiy’s centralization efforts, bloodshed may follow.

Regional destabiliser

There is growing concern that the conflict may destabilize the entire Horn of Africa. Thousands of Ethiopian soldiers fighting Islamist insurgencies in Somalia have reportedly been withdrawn to join to the Tigray offensive. This redeployment could create a power vacuum in Somalia to be filled by Islamist groups like al-Shabaab or the Islamic State. The violence in Tigray has already spilled into neighbouring Eritrea, which harbours a longstanding animosity towards the TPLF over its leading role in Eritrean-Ethiopian border conflict. Eritrean troops are reported to have crossed into the Tigray region following TPLF rocket strikes on the Eritrean capital of Asmara.

Eritrean involvement could potentially result in intervention from other foreign powers. Abiy is currently engaged in a public standoff with Egypt and Sudan over the GERD project which, when completed, will grant Ethiopia control of the Nile water supply. If Egypt and Sudan were to side with the TPLF, derailing the GERD, this could result in more actors becoming involved in the crisis. For example, Turkey, with its history of intervening in post-Arab Spring conflicts in Syria and Libya, may move in to balance its regional rival Egypt by supporting Ethiopia. With Turkey involved, it would potentially not be long before the Gulf states, who have vested interests in the Horn, would get dragged into the conflict.

Walking a fine line

With these internal and external variables at play, it is in the interest of Abiy and his government to seek an immediate end to the Tigray conflict – either through swift military means or international mediation. The latter seems preferable for producing a more robust and enduring peace agreement, with the eventual reintegration of Tigrayan politicians into Ethiopian politics. Abiy, however, must be careful not to make too many concessions, lest he alienate his support base and incentivise other secessionist movements in the country.

To secure its future, Ethiopia must move beyond ethnic-based politics. Lessons from Yugoslavia in 1990s have demonstrated the innate and deadly fallacies of ethnic federalism. Ethiopia’s ethnic federalist system serves to empower the dominant ethno-regional group, thereby marginalizing ethnic minorities at the local level. In creating a unitary state, Abiy must reject the populist demands of the Amhara or Oromo while working toward peaceful coexistence with the TPFL. Inclusion into the PP might prove a stretch but Abiy should at least strive for a working relationship with the TPLF that offers them political protections in a new Ethiopia.

Farley Sweatman is a Master of Global Affairs (MGA ’21) Candidate at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, University of Toronto. He has interned at the American Chamber Commerce in Morocco and is currently specializing in global capital markets and global security at the Munk School. Farley is also an active member of the Global Conversations media organization as Associate Editor and former Feature Contributor for Middle East and North African (MENA) Affairs.