by Gideon Jones

Though the Northern Ireland of today is a vastly different place than it was when the Troubles began in 1968, it would be a mistake to assume that those original divisions have completely healed. Despite boasting one of the lowest murder rates in Western Europe, the divisions that led to the conflict are still present, with both the Protestant and Catholic communities still living largely separated from one another, without a strong shared identity to unite them and with the Loyalist and Republican labels remaining salient. Brexit, however, is now threatening to lay bare this sectarian division like no other event ever has. Unfortunately, many are now asking themselves whether the UK leaving the European Union (EU), especially without a deal, will see the return of terrorism in Northern Ireland.

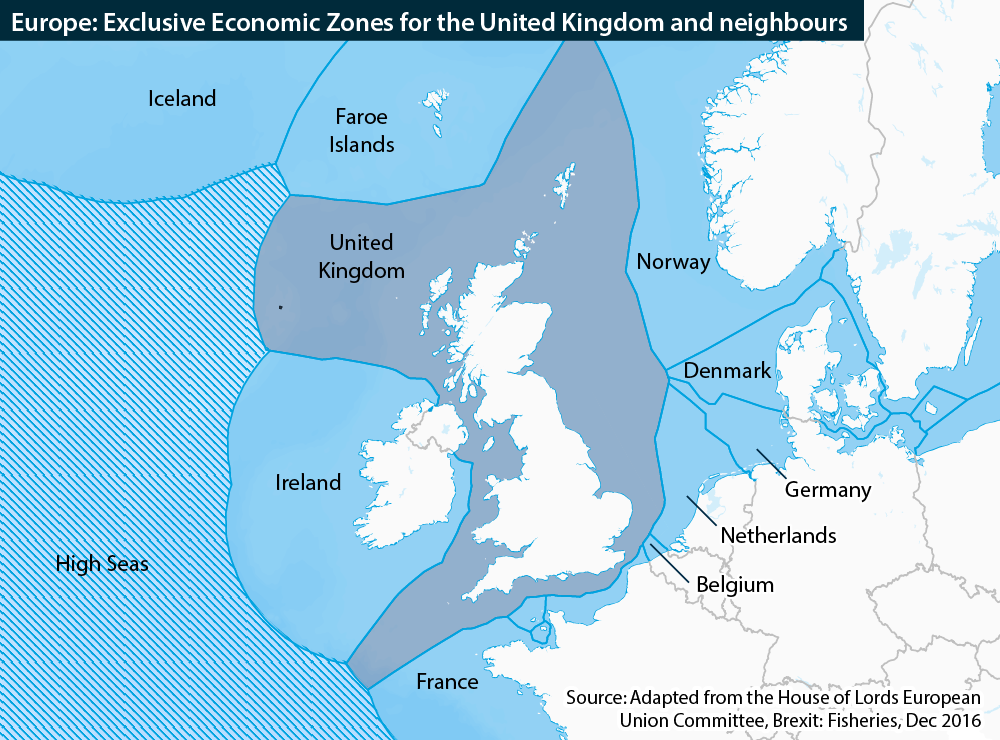

The question of Northern Ireland, and by extension its border with the Republic of Ireland, held only a minor position in the Brexit referendum discourse, some campaigners even denied the very existence of the issue. Regardless, the border has remained a thorn in the side of successive British Prime Ministers. The main concern has been with the economic arrangements that need to be put in place once the UK leaves the EU. What makes this an even more contentious issue in Northern Ireland is that eighty five percent of Catholics voted to remain, whilst sixty percent of Protestants voted to leave. This split along religious lines is concerning to say the least. Britain’s membership in the EU allowed an invisible border to exist between North and South, allowing communities on both sides to remain in close contact, as well as unhindered passage of goods and people. This was a settlement that most in Northern Ireland were happy to keep in place, but Brexit will be seen by many in the Catholic (as well as forty percent of the Protestant) community as being imposed on them by the British against their will.

The prospect of a united Ireland is still an ideal that holds a great deal of weight in the Catholic community, and many persist in rejecting the legitimacy of Westminster (with Sinn Fein still declining to take their seats). Perception matters, and Brexit looks to a great deal of Catholics like a political project of a distant power, meddling in their lives with little to no concern for their needs, or even their consent. If a border and custom checkpoints were to be created through a no-deal scenario, the resentment it would cause amongst Catholics can hardly be understated. Indeed, they would likely become useful recruiting tools for Dissident Republicans, as well as a targets for terrorist attacks.

The threat posed by terrorist and paramilitary groups remains a very real one. Though the Provisional IRA loyalist paramilitaries like the UVF and are unlikely to mount any campaign of violence similar in scale to that of The Troubles, according to a 2015 governmental report, all the main paramilitary groups are still in existence and remain a potential national security threat . The main Republican and Loyalist groups remain committed to achieving their political aims through peaceful means. In contrast, Dissident Republicans continue to carry out an armed campaign to end what they see as British imperialism on the island of Ireland. Dissident Republicans, those republicans who rejected the Good Friday Agreement, are still actively opposing the peace through groups like the New IRA, and have been responsible for several attacks in Northern Ireland, as well as the death of the journalist Lyra McKee. There is a good reason to believe that groups like the New IRA will attempt to capitalise on Brexit and the discontent that it will cause, and may use it as a way to draw many young and disaffected Catholics into their ranks, carrying out further attacks across Northern Ireland.

There is no doubt that Dissident groups would have attempted to carry out attacks with or without Brexit. In fact, it could be argued that Brexit has simply brought into sharp focus the violence they have been carrying out in Northern Ireland for years. The real danger, however, is that Brexit can provide them an opportunity to get back into the spotlight, and to once again legitimise violence as a way of achieving political aims. Brian Kenna, the chairman of Saoradh, a small republican party in Northern Ireland thought to be the political arm of the New IRA, claimed that:

“Brexit is a huge opportunity. It’s not the reason why people would resist British rule but Brexit just gives it focus, gives it a physical picture. It’s a huge help.”

Dissident Republicans will see Brexit, and especially a no-deal, as an opportunity too good to resist passing up - there is a very real chance that they will seek to exploit underlying resentments and take violent action. Though they may receive a bump in support and could feel emboldened by the political landscape, it remains unlikely that we are witnessing the return of The Troubles.

Whilst Northern Ireland’s political landscape may be going through a shift due to Brexit, it is not yet a forgone conclusion that people will give up on democratic means of achieving their political goals. In fact, many non-violent supporters of a united Ireland are feeling more confident of achieving it after Brexit, and believe that, in time, unification will be won through the ballot box.

It is not without some irony that as Northern Ireland approaches its centenary, there is a strong chance that it will have a Catholic majority. It would be a mistake, however, to assume that this will automatically translate into majority support for a united Ireland. Being Catholic no longer equates to being a nationalist, nor does being Protestant mean you are a unionist, with recent polling showing that people are feeling less bound by tribal loyalty and are increasingly neutral on Northern Ireland’s union with the UK. This though does mean that Northern Ireland is no longer the Protestant state for a Protestant people as it was originally envisioned to be - and the state’s ties to Britain will more likely be decided on pragmatism rather than a deep cultural or religious affinity. Republicans are given to feeling that time is on their side, and Brexit may have just sped up the process of reunification. There is moreover a deep feeling within both Protestant and Catholic communities that reunification with Ireland is more a matter of ‘when’, rather than ‘if’, as support for a united Ireland goes up, but also due to a feeling among Unionists that the British people increasingly no longer care if they stay or go.

So, will Brexit bring about a return to the Troubles in Northern Ireland? Dissidents will undoubtedly use it as an opportunity to carry out attacks and increase their own levels of support.

But a return to the Troubles? This is possible, yet highly unlikely. Politics is thankfully still seen as the arena to advance one’s goals, and the ballot box is still seen as more powerful than the bomb.

Gideon Jones is a MA student in Terrorism, Security & Society at the War Studies Department, King’s College London, and completed his BA in History at the University of Warwick.

Coming from Northern Ireland, he has been brought up in a country scarred by the issues of terrorism, conflict, sectarianism, and extremist ideology. Through this experience, he has been given valuable insight into how the legacies of such problems can continue to divide a society decades after the fighting has stopped, and how the issues left unresolved can threaten to upend a fragile peace.

Gideon is a Staff Writer at Strife.