by Daria Platonova

5 June 2019

Volodymyr Zelenskiy’s[1] election to the presidency in Ukraine[2] has taken everyone by surprise. A former comedy actor and producer, Zelenskiy is widely seen as someone “outside the system,” despite having connections to the Ukrainian oligarchs. In the few interviews that he granted prior to the election, he acknowledged that the conflict in the Donbas is the most serious problem facing Ukraine. In this article, I discuss Zelenskiy’s views on how to resolve the conflict and his options.

During the presidential campaign, Zelenskiy appealed to the softer, compassionate side of his voters and detractors by saying that he did not want Ukrainians to continue dying in the Donbas, therefore a ceasefire and the return of all prisoners of war to Ukraine is essential. In the televised debate with the outgoing President Petro Poroshenko on 19 April 2019, he blamed Poroshenko for the massive loss of life in Iloviask (August 2014) and Debaltseve (February 2015), when the Ukrainian forces were repulsed by the separatist and Russian state forces. In his inauguration speech on 20 May, Zelenskiy reiterated these ideas. It can be argued that this appeal to the “war weariness” of Ukrainians has won Zelenskiy so many votes, especially in the east.

In relation to more concrete proposals, Zelenskiy’s position has been more vague. Contrary to the political premise of the Minsk Agreements, Zelenskiy has ruled out an autonomous status for the separatist republics within Ukraine. He argues that Ukraine should re-establish its sovereignty over the entire territory of the Donbas and Crimea, he supports the idea of a peacekeeping force in the Donbas, and proposes “reformatting” the Minsk Agreements, which presupposes the inclusion of the US and Great Britain in the negotiations. To Ukrainian commentators, these proposals are not radically different from those made by the previous administration. Moreover, they are somewhat contradictory, in that, on one hand, Zelenskiy wants a dialogue with Russia and the separatists and, on the other, he wants to “fight until the end” to regain what belongs to Ukraine.

Several developments have taken place since Zelenskiy’s victory. His stance towards Russia has somewhat hardened. For example, he reacted vitriolically towards Vladimir Putin’s decree to simplify the issuance of Russian passports to the residents of separatist-controlled parts of Ukraine, pointing out flaws in the current Russian regime. As of now, he refuses to launch direct talks with Russia. At the same time, it is significant that, despite the pressure from international representatives, such as the US Special Representative in Ukraine Kurt Volker, Zelenskiy has not spoken of complete disarmament and elimination of the local separatist administrations in Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics. He however continues to believe that the separatists are “not independent actors”.

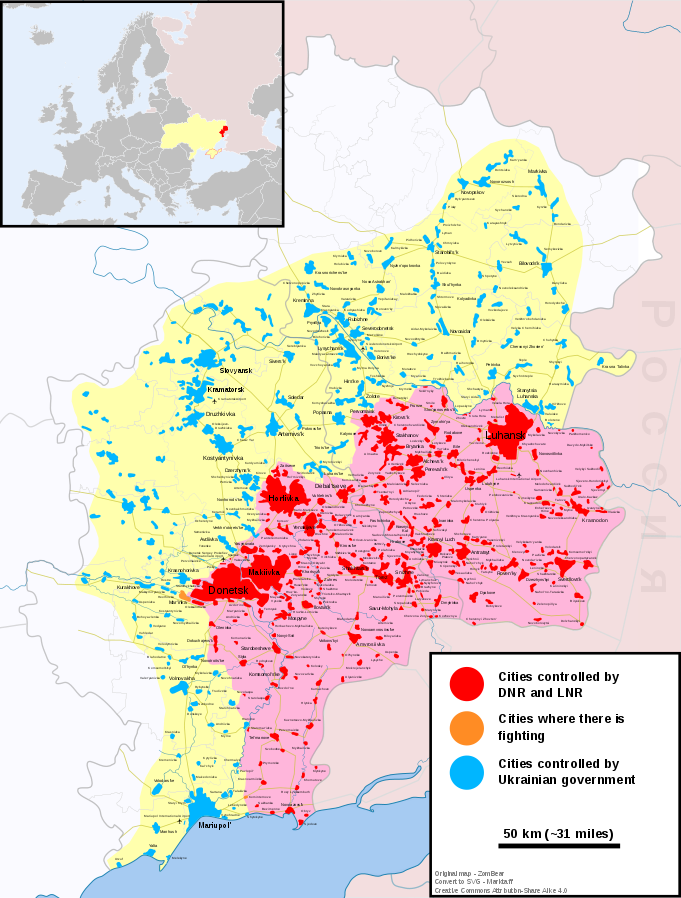

When considering Zelenskiy’s options as to resolving the conflict, we must take into account that, despite the seeming simplicity of how the conflict has been reported (low-intensity fighting, both Russia and Ukraine alternately depicted as aggressors and fighters for sovereignty/freedom), the developments in and around the conflict zones have reached an unprecedented complexity. The rebellious republics have amassed significant resources – even if many are imported from Russia, especially military hardware - and demonstrated considerable legislative and state-building capacity. They are now deeply entrenched, while the republics’ people are not at all eager to be integrated back into Ukraine.[3] The republics’ leaders are highly sceptical about Zelenskiy’s proposals. If we recall the situation back in May 2014 when “launching a direct dialogue with the separatists” was one of Poroshenko’s campaign promises, and he failed to follow it through, even if the nascent break away states were still in their infancy and their military capacity was small, we can expect that Zelenskiy is unlikely to suddenly start talking to the separatists directly.

Secondly, the understanding of how to follow the Minsk Agreements and whether they actually work differs between Russia and Ukraine. One suspects that both sides misinterpret the agreements deliberately because they see to take advantage of the current situation and promote their own agendas. All these years, Russia has kept insisting – as do the separatist leaders – that Ukraine must stop its “punitive operation,” in the Donbas and grant it a special status within Ukraine. This is Russia’s main objective. Ukraine insists that Russia must stop supporting the republics militarily and free the territories of the Donbas. Amid the flurry of diplomatic talks at many levels along these lines, both sides continue attacking each other positions and people continue to die. It seems that, for Ukraine under Poroshenko, the Donbas conflict turned into an opportunity to build a powerful military force and disassociate itself from Russia completely. Therefore, the separatists had a point when they argued that Poroshenko sought to use the conflict to “salvage his regime”. For Russia, the Donbas is a military and state-building project, a testing ground for new military technology and an attempt to exert its influence on the politics in Ukraine. Ukrainians therefore are right when they say that Putin is using the conflict to keep up his regime.

Zelenskiy therefore is likely to continue relying on diplomatic talks. Perhaps, he would be less insistent on the major international players’ roles in resolving the conflict as Poroshenko was. Zelenskiy’s most recent decision to put the conflict resolution to an all-Ukrainian referendum indicates a move in this direction. In line with the “human side” of his campaign promises, he would try to contain the violence in the conflict zone and avoid a full-fledged war with Russia. When Poroshenko became president in 2014, straight after his victory, the most vicious fighting followed in Donetsk Airport. According to some reports, Poroshenko ordered an offensive aimed at retaking the airport, even before he was sworn. He then was caught up in the unenviable cycle of “action-response,” as the separatists built their armies and Russia provided them with support. Zelenskiy is much luckier in this respect in that no significant fighting followed his victory. He is therefore unlikely to suddenly ramp up the military effort in the Donbas.

Daria is a PhD student at King’s College London. Her research focuses on the political protests and conflict in eastern Ukraine, 2013 - 2014. She led one of the Causes of War seminars in the War Studies Department in 2017. Prior to joining King’s, she worked as a teacher. She graduated with a degree in History from the University of Cambridge in 2011. Her broader interests include European history, war studies, and interdisciplinary methods.

[1] The spelling is consistent with the English spelling as it appears in Kyiv Post, the major English-language news and opinion outlet in Ukraine.

[2] Zelenskiy won a landslide victory across the majority of Ukrainian regions, except in Lviv in the West of Ukraine, with 73.22% of the vote. Petro Poroshenko won 24.45%.

[3] See also comments on Vkontakte social media pages and my sporadic conversations with some people from Donetsk online.