by Guanie Lim & Yat Ming Ooi

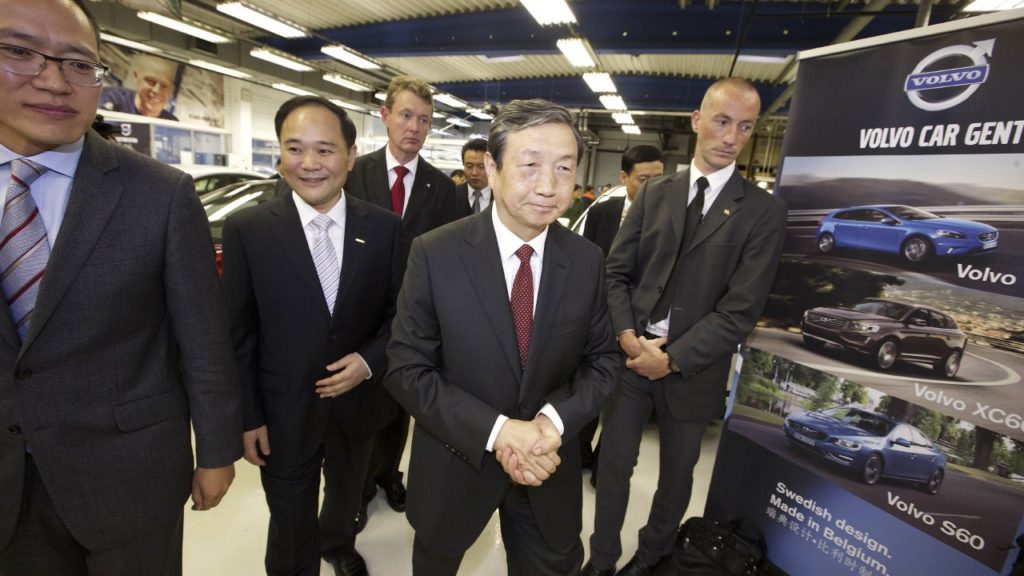

‘The Fortune Global 500 is now more Chinese than American’. The headline piece of Fortune Magazine’s edition of August 2020 revealed much about the nature of global business. With more companies based in Mainland China and Hong Kong (124) than in the US (121), the list sparked intense debate China’s perceived ascendancy in the international economy. Following four decades of rapid growth, this is a clear image of what is conventionally known as China Inc. Searching for market share domestically as well as abroad, these Chinese firms (occasionally termed ‘national champions’) are known for their acquisition of large and well-established firms such as IBM, Club Med, and Volvo. Against the backdrop of an increasingly strained relationship between the US and China and instances of some countries pushing back against Chinese infrastructure deals in the Global South, a dual question can be asked: where is this rivalry headed to? And, what are the implications for the rest of the world?

Chinese Corporate Power

The Global 500 is a prestigious list and offers arguably the best snapshot of the state of global business. In its methodology, firms are ranked based on revenue. This approach is somewhat biased as it tends to favour companies operating highly regulated monopolies/oligopolies in large economies. Many Chinese companies fall into this category. Indeed, an analysis of those 124 Chinese companies in the Global 500 reveals that many are operating de facto monopolies/oligopolies in the domestic market, where non-tariff barriers remain high. Examples include Sinopec Group, State Grid, and China National Petroleum (all located within the top 4). Operating in chemicals, power, and petroleum respectively, these three firms are not only state-owned but also generate much of their revenue in highly-regulated, capital-intensive industries. Further down the pecking order, a similar trend emerges: of the twenty-four Chinese companies in the top 100, almost all operate in industries such as banking, insurance, construction, and mining.

At the same time, there is also a paucity of Chinese manufacturing firms on the list. This odd development has occurred despite Beijing’s push for ‘national champions’ in industries such as automobile production, steelmaking, shipbuilding, and aerospace. However, only two manufacturing firms – Huawei (private; 49th) and SAIC (state-owned; 52nd) – made it into the top 100.

Huawei can be described as a non-traditional firm in the manufacturing industry since a relatively large portion of its revenue is derived from what are essentially service activities (telecommunication installation, consulting, and repair). Even in the manufacturing of its renowned smartphones, core components are still sourced primarily from Western and Japanese business groups. For example, the Huawei P and Mate Series – which come with high-definition cameras – rely on German company Leica for the supply of camera-related components. Despite Huawei’s attempts at expanding into global markets, the firm continues to face difficulties in some markets, due to allegations of undue state support, and cybersecurity concerns. Most recently, its Chief Financial Officer has been under house arrest in Canada. In addition, the US has stepped up pressure on its allies to remove Huawei equipment from their telecoms infrastructures over concerns that the Chinese government could possibly lean on the company to allow it to conduct espionage, closely followed by the UK. Although it is premature to write off Huawei at this stage, it seems to be one of the highest-profile targets ensnared in the trade war between the USA and China.

For SAIC, an automobile player based in Shanghai, the outlook is somewhat better. Since its joint-venture with Volkswagen after the 1978 economic reforms, SAIC has been able to continuously strengthen its position in the domestic economy, emerging as a de facto lead firm. In the Global 500 list for 2020, it is ranked as the seventh-largest automobile company, surpassing brand name rivals such as BMW Group and Nissan Motor. However, like Huawei, there does not seem to be enough incorporation of critical manufacturing technologies, which forces SAIC to rely on more mature foreign companies. SAIC still sells vehicles from a variety of brands licensed from mainly Western automobile companies, in exchange for entry to the Chinese market. As of 2020, only two of its brands, MG and Roewe, have had (limited) success outside China. These two brands were acquired during the mid-2000s from now-defunct British carmaker MG Rover.

For the MG brand, in particular, SAIC’s internationalisation efforts have been bumpy. In 2012, SAIC entered into a joint venture with Thailand’s largest conglomerate, Charoen Pokphand (CP) Group, to produce MG cars in Thailand. With an annual production capacity of fifty thousand vehicles at the outset (which could increase to two-hundred thousand units), the company aspired to capture the Thai as well as the adjacent Southeast Asian markets. However, here again, progress has been slow. SAIC only managed to sell 23,740 MG vehicles in 2018, well below its total production capacity of 200,000 units. By capturing only a 2.3% market share in the Thai market, SAIC has failed to make a dent in the Japanese-dominated automobile market of Thailand (and by extension Southeast Asia).

Chinese Catching-Up in Retrospect

The experiences of Huawei and SAIC are sobering. Although undoubtedly ‘national champions’ in their own right within the large domestic market of China, there is not enough evidence to suggest they have become the sort of ‘global champions’ that successive Chinese politicians and bureaucrats frequently exhort them to be, nor are they necessarily setting the example for other national firms. Perhaps this suggests some underlying problems with China’s technological catching-up that goes unmentioned in both the euphoria surrounding the ‘rise of China Inc.’ and the pessimism engulfing the increasingly tense international economic environment? What we are advocating here is to step back and scrutinise both sets of development. While not denying China’s economic strengths, there is an equal need to unpack the nature of the Chinese economy.

As illustrated in the previous paragraphs, Chinese growth is mainly driven by a large domestic market, which obviates the need to create competitive firms with world-beating indigenous technologies. Chinese technological shortfall can instead be plugged by purchasing production and process expertise from foreign firms (through royalty payments for copyrighted products and mergers and acquisitions, for example), resulting in a dearth of genuine manufacturing ‘national champions’, for which long-term investment in R&D is required. If the fate of Huawei and SAIC is of any relevance, then we must more seriously take manufacturing as a key cog of development. More broadly, while one may like to envision a post-industrial society, no economy – barring small, wealthy offshore financial centres (e.g. Macau and the Cayman Islands) – transitioned straight into the high-income category without a competitive manufacturing sector. Without a strong manufacturing sector (and by extension command of technology), talks about a US-China trade war is overblown as China Inc. might not have the strategic depth to mount a sustained challenge.

The USA: Still No. 1?

Moreover, in the US, the situation is nowhere near as dire as what the popular media seems to suggest. Despite numerical superiority, Chinese companies account for only twenty-five per cent of the total Global 500 revenue against the US’ thirty per cent. Furthermore, two US companies made it into the top 10 – Walmart (first) and Amazon.com (ninth). Walmart, in particular, claimed the top spot for the seventh consecutive year.

In addition, thirty-four US companies made it into the top 100, outweighing the twenty-four hailing from China. Although US companies in the Global 500 participate heavily in service activities, it must be noted that some of the manufacturing behemoths have maintained or even enhanced their positions. In the top 100 roster, USA Inc. is represented by Ford Motor (31st), General Motors (40th), Microsoft (47th), and Dell (81st). Ford Motor and General Motors represent the mature automotive industry, while the latter two represent the more forward-looking information technology industries.

Amid the seemingly meteoric rise of Chinese companies, the US retains three salient points that will determine the outcome of the much-hyped trade wars. The first point that often goes unnoticed is the early mover status of US companies, which allow them to go abroad far more easily than companies originating from latecomer economies such as China and India. The US (and by extension, its cohort of companies) remains popular in many parts of the globe, in turn giving US companies quite simply the benefit of the doubt, a privilege that Chinese firms do not enjoy (at least for now). Take, for example, the ban that prohibited Huawei and ZTE from participating in Australia’s 5G network development. A cue the Australians took from the US.

The second point concerns the innovative capabilities of US companies. Historically, the US and other Western countries are famed for their ability to innovate. By innovating, we mean to create something new, and implementing it in the production process or bringing it to market as a new product. While US companies are moving some production out of China, this is unlikely to affect their ability to innovate as communication technologies have improved companies’ ability to innovate throughout their value chain. It is through the ability of US companies, often with support from the state, to continually renew and reinvent themselves that we see US companies extending their early mover advantage in the long run.

The final point brings our analysis into the behavioural realm. US companies have market-shaping capabilities. In other words, these companies can dictate what customers and consumers need and want in the US and global markets. No one knew we needed an MP3 player until the late Steve Jobs told us it is ‘cool’ to own an iPod. We had no idea we needed boutique takeaway coffee too. That is until Howard Schultz told us we should all be sipping on a barista-made, grande, vanilla latte with low-fat milk from Starbucks. Of course, there was more to the iPod story. Apple was excellent in crafting an ecosystem strategy, which created network and lock-in effects. The ability of US companies to create new demand, tap previously untapped markets, and influence consumer choices, reinforces US Inc.’s position in the global market.

Is China Inc. taking over from US Inc. any time soon? The short answer is no. Chinese companies are performing well in the globalised and connected world we live in today. But (most) open and transparent economies are ‘suspicious’ of Chinese companies’ intentions. Will China Inc. prevail if we have a full-blown trade war between the two largest economies? Maybe. Chinese companies are still learning and expanding. Moreover, they have the Chinese and surrounding Asian markets to fall back on if indeed a full-scale trade war materializes. Regardless, we can conclude that the US can prevail if it continues to do what it does best – extend its early mover advantage through innovation, market-shaping capabilities, and lock-in effects.

Guanie Lim is Research Fellow at the Nanyang Centre for Public Administration, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. His main research interests are comparative political economy, value chain analysis, and the Belt and Road Initiative in Southeast Asia. Guanie is also interested in broader development issues within Asia, especially those of China, Vietnam, and Malaysia. In the coming years, he will be conducting comparative research on how and why China’s capital exports are reshaping development in key developing regions – Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa. He can be reached at guanie.lim [at] gmail.com

Yat Ming Ooi is Research Fellow in the Department of Management and International Business, The University of Auckland, New Zealand. He is also Adjunct Lecturer at Swinburne University of Technology, Australia. His main research interests are innovation management, technology and science commercialisation, and business models. Yat Ming is also interested in the role of new research funding policy plays in addressing grand challenges. He can be reached at y.ooi [at] auckland.ac.nz