By Clément Briens

This article is a follow-up to my previous blog entry, that examined French national cyber strategy, and which can be found here.

More fear than harm

The WannaCry ransomware that plagued the National Health Service (NHS) in May 2017 served as a wake-up call for many, as it demonstrated the vulnerability of the UK’s critical infrastructure. Public dialogue concerning the state of the British cyber policy and security has ensued following this attack, with the USA pointing fingers at North Korea for the aggression and many British news outlets questioning the government’s cyber defence capabilities. While WannaCry was relatively harmless, and it is still unclear if it was an intentional attack on the UK or simply a viral malware, one can imagine the potentially disastrous consequences of future cyber-attacks on other parts of the UK’s national infrastructure.

Fortunately, UK policymakers have heeded this warning, and have allocated an extra £21 million “to increase the cyber resilience of major trauma sites as an immediate priority”. This response is a first real-world application of the UK’s 2016–2021 National Cyber Security Strategy paper, and the first successful application of its principles. This article will argue that such a strategy paper is a leading example of how to deploy a national cyber strategy, although it is not perfect.

The strategy’s main strengths are that it seeks to build up resilience rather than just blindly upping the offensive ante; to raise public awareness and initiate a public dialogue; and to invest in the country’s youth to find the solutions to future problems. The first part of this article will be spent examining how these aims have successfully been translated into practice. However, the second part of the paper will observe how the UK is failing to secure its election infrastructure, which is a major shortcoming in its national strategy.

Reaffirming resilience

As mentioned above, government responses have sprung relatively quickly following the WannaCry intrusion of the NHS to give it the tools it needs to fend off future attacks and malware. This rapid cure to the national security hangover demonstrates one of the tenets the application of the main principles outlined in the paper, the “3-D” strategy: defend, deter, and develop.

Developing resilience is an objective that involves all three aspects of this 3-D strategy. Indeed, UK businesses should collaborate with public actors to develop security solutions for both sectors in order to help defend companies and public organisations more effectively, which hopefully will deter future attacks.

This strategy has been taken very seriously by Chancellor Phillip Hammond, who in 2016 had pledged £1.9 billion in support of these cyber initiatives. Such an effort provides resources for the main UK actors such as the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) and Government Communication Headquarters (GCHQ); and it also supports the creation of the Cyber Security Research Institute (CSRI).

Policy Parley

Another crucial aspect of the 2016–2021 National Cyber Security Strategy paper is public engagement and training. To this extent, a plethora of government initiatives have been enforced, with the objectives to raise awareness and construct dialogue with the individuals, companies and academics. Two of these campaigns are known as Cyber Aware and Cyber Streetwise, the former of these being explicitly aimed towards small businesses:

Furthermore, efforts have been made to keep academics in the loop. The NCSC’s Cyber Security Body of Knowledge initiative, dubbed CyBOK, has united an academic consortium including professors from Oxford, Imperial, UCL and others, with their aim being “to codify the cyber security knowledge which underpins the profession”.

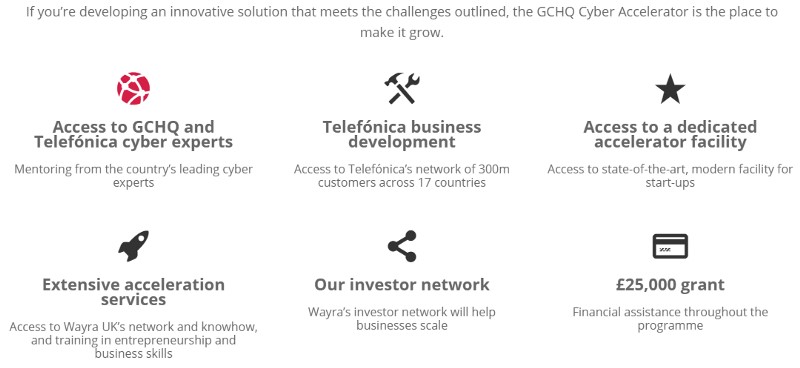

Meanwhile, the NCSC is debuting its “Cyber security academic startups programme”, which aims to provide academic startups with grants up to £16,000, GCHQ are also holding their Cyber Accelerator programme to challenge the cyber-security startup community to “ develop new tools and prototypes that enhance or enable security on existing devices”.

Training Teens

Another of the key points of the National Strategy is to tap into the vast potential of young adults and others that have benefited from the democratisation of cyber tools and refine this raw talent into a key asset. Efforts have been made to recruit imaginative youths with coding skills: the development of interactive websites such as the Cyber Discovery website acts as an assessment tool for the Cyber Schools programme, which aims to recruit teenagers from ages 14–18.

The Catch

The conclusion of the first part of this article is that the UK is excelling in building resilience and investing in cyber security, two edges of the same cyber-sword that provides protection to the country.

However, there is a significant flaw in the National Cyber Security Strategy: the absence of a classification of voting technology and the electoral process at large as part of the country’s Critical National Infrastructure (CNI). This prevents voting technology from benefitting from CNI-grade cyber security. The WannaCry blunder has demonstrated how actors can easily paralyze the UK’s health system, which is why Britain urgently needs to secure other aspects of its critical infrastructure, such as its democratic institutions.

Cyber-crime poses a major threat to Western democracies, as official reports are accusing foreign groups of interference in the recent American, French, German, Spanish, and British elections via cyberspace. The risk for upcoming elections in Italy in March and the EU Parliament next year is genuine. Theresa May has already expressed her concerns with the meddling in the Brexit referendum in particular.

However, in practice, not much has been done to bolster cyber security in regards to voting technologies. For example, a May 2017 Parliamentary Office of Security and Technology (POST) report analyses foreign involvement in British CNI. However it only identifies such involvement in two sectors: supply chain involvement (Chinese hardware being used by various critical sectors) and foreign investment and direction.

Furthermore, a US Senate Committee of Foreign Relations report published January 10th examining the impact of Russian interference on Western democracies holds a particular statement concerning the UK:

“British officials stated after the poll that there was ‘‘no successful Russian cyber intervention’’ into the election process seen and asserted that systems were in place to protect against electoral fraud at all levels, though it is unclear the extent to which the lack of meddling may have also been due to a shift in the Kremlin’s approach.”

Over-confidence in capabilities has never been a good sign in military history; cyber security is no exception. Projects of introducing online voting by 2020 will only exacerbate the risk that foreign governments or independent actors will seek to influence the outcome of British democratic processes. Voter identity theft is now a frightening possibility, as hackers can purchase massive datasets of voter information on the dark web in order to usurp voter identities online and alter votes. The modification of voter locations, hence making their votes void, is also a concern. While the rise of blockchain technology may be the solution for both transparency and security in online election processes, a reverse trend can be found in other European countries such as the Netherlands and France that are in fact abandoning online voting.

Curbing the Hubris

Introducing online voting would be a step in the wrong direction towards safeguarding British democracy, as it would expose voting to the same risks as other CNI sectors that are now controlled though the internet, without putting it under security standards that CNI benefits from. Placing British election infrastructure under CNI security standards would be the better option in this matter.

Another broad conclusion that we can make is that this 2016 paper may already be outdated. Five-year plans in the age of cyber security may not be the best answer, as the boundaries of cyber criminality and foreign interference are being pushed every day. Regular updates must be publicly and periodically published to address recent developments such as the WannaCry attack, the alleged Russian interference in US elections, and how the British government plans on dealing with these developments.

Clément Briens is a second year War Studies & History Bachelor’s degree student. His main interests lie in cyber security, counterinsurgency theory, and nuclear proliferation. You can follow him on Twitter @ClementBriens

Image Credits

Image 2: http://arenaillustration.com/blog/steve-may-cyber-streetwise-website-billboards/

Image 3: https://wayra.co.uk/gchq/

Image 4: https://joincyberdiscovery.com/

Image 5: https://www.politico.eu/article/why-we-lost-the-brexit-vote-former-uk-prime-minister-david-cameron/

Clément Briens

Clément Briens is a second year War Studies & History Bachelor’s degree student. His main interests lie in cyber security, counterinsurgency theory, and nuclear proliferation. You can follow him on Twitter @ClementBriens