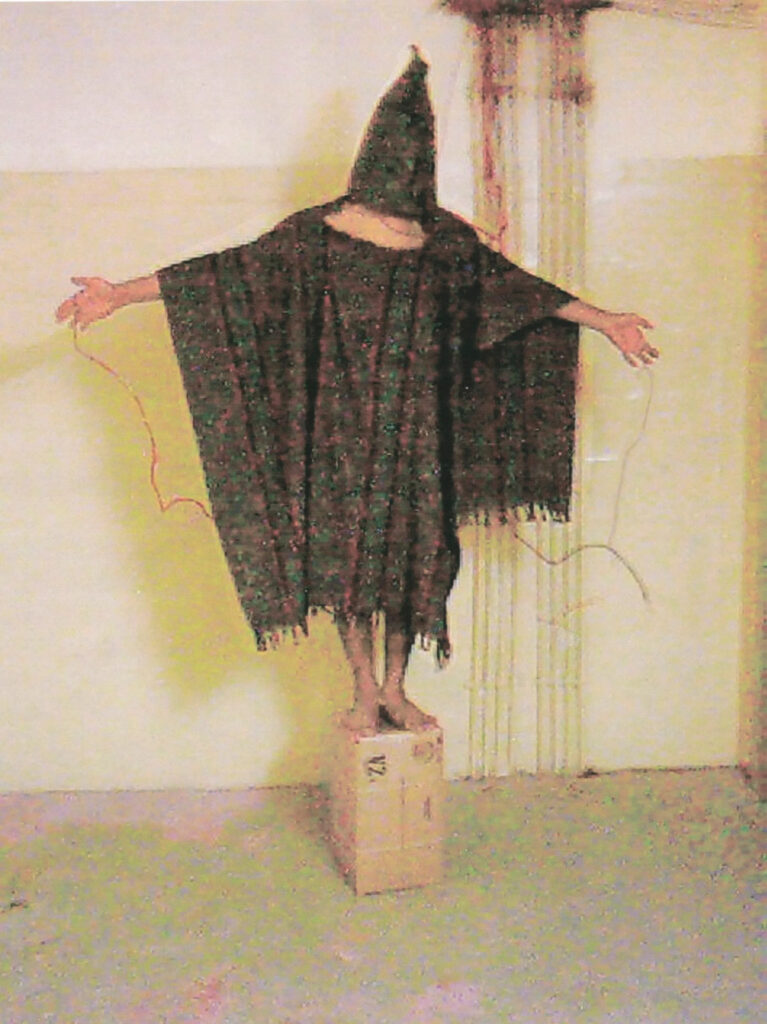

The Torture Memos are a collection of documents from the US Justice Department Office of Legal Counsel regarding the use of torture against alleged members of al-Qaeda. The basic motivation of these documents was to determine whether the United States’ practice of “enhanced interrogation techniques” constituted torture under US and international law. They unilaterally justified the US’ practices. After the memos were leaked in 2004, they were lambasted as a clear disconnect from the War on Terror’s emphasis on protecting human rights. The memos are an extension of the legal strategies used to legitimize violations of liberal principles in order to maintain U.S. hegemony and empire. In this article, I will discuss the basic provisions of the torture memos. The next installment in this series will focus on the implementation and impacts that the Bush Administration’s controversial legal strategies caused.

Narrow Interpretations, Broad Implications

The first memo, titled Standards of Conduct for Interrogation under 18 U.S.C. §§ 2340-2340A, was authored by Jay Bybee, then-Assistant Attorney General, on 1 August 2002. Addressed to Counsel to the President, Alberto R. Gonzales, this document breaks down Section 2340 and requests the Office of Legal Council’s opinion on what constitutes torture under this statute. Bybee’s arguments are vague, and many were later determined to be untrue. From the earliest sections of this memo, Bybee asserts that torture is a very narrow practice according to Section 2340. He states the statute “makes it a criminal offense for any person ‘outside of the United States to commit or attempt to commit torture,’” adding that the statute defines torture as an “act committed by a person acting under the color of law specifically intended to inflict severe physical or mental pain or suffering… upon another person within his custody or physical control.”[i] Bybee hones in on the language of the statute, stating it “requires that severe pain and suffering must be inflicted with specific intent…” adding “the defendant had to act with the express ‘purpose to disobey the law’ in order for the mens rea element to be satisfied.”[ii] According to Bybee, infliction of pain without “specific intent” does not violate the statute. If a defendant commits an act that does inflict pain with the knowledge that pain is likely, but not certain, “general intent” is satisfied, disqualifying the perpetrator from torture.[iii] Bybee further dissects the language of the statute, arguing that it does not define “severe” in relation to physical pain and “prolonged” in relation to mental harm. Bybee’s interpretation is that torture, as defined by Section 2340, is “not the mere infliction of pain or suffering on another, but is a step well removed. The victim must experience pain…equivalent to the pain that would be associated with serious physical injury so severe that death organ, failure, or permanent damage resulting in loss of significant body function will likely result. If that pain or suffering is psychological, that suffering must result from one of these acts outlined in the statute, in addition, these acts must cause long-term mental harm.”

In section II, Bybee argues that international law reinforces his interpretation of 2340. He references the UN Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT), which states that torture is

“any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.”

In response, Bybee states, Accordingly, severe pain or suffering need not be inflicted for those specific purposes to constitute torture; instead, the perpetrator must simply have a purpose of the same kind… the pain and suffering must be severe to reach the threshold of torture.[iv]”

Bybee authored another memo titled Interrogation of al Qaeda Operative in which he addressed John A. Rizzo, General Counsel of the CIA, following a similar request to that of the Gonzales. This document covers the torture of Abu Zubaydah and goes into detail about the interrogation practices in question. At the time, Zubaydah was incarcerated in the US under the presumption that he had information on terror cells and plots in the US and Saudi Arabia. According to Rizzo and the CIA, the level of “chatter” surrounding the supposed cells warranted an “increased pressure phase” which was ultimately the interrogations involving torture. He states that the “interrogations” will last “no more than several days but could last up to thirty days” and will employ 10 techniques to “dislocate expectations regarding the treatment he believes he will receive and encourage him to disclose the crucial information” and employ ten different methods.[v] In describing these methods, all of which involve a degree of physical pain, discomfort, and/or mental strife, the illusion to specific intent is seen. In describing one of these methods, called “facial/insult slap” where an interrogator slaps a prisoner in the face in such a way to increase pain, he writes the intent is to “not inflict physical pain that is severe or lasting. Instead… to induce shock, surprise, and/or humiliation.”

Waterboarding is one of the more infamous methods that the US employed during its duration of the use of torture. Bybee’s memo discusses the practice in detail, and establishes the Bush administration’s legal strategy around this unsavoury tactic as follows:

“…the individual is bound securely to an inclined bench… The individual’s feet are generally elevated. A cloth is placed over the forehead and eyes. Water is then applied to the cloth in a controlled manner. Once the cloth is completely saturated and covers the mouth and nose, air flow is slightly restricted for 20 to 40 seconds… this causes an increase in carbon dioxide in the individual’s blood. This increase in the carbon dioxide level stimulates increased effort to breathe. This effort plus the cloth produces the perception of ‘suffocation and incipient panic’ i.e., the perception of drowning.” He continues by stating “You have orally informed us this procedure triggers an automatic physiological sensation of drowning that the individual cannot control even though he may be aware that he is in fact not drowning.” Bybee also acknowledges technique will be used on Zubaydah stating a medical professional would be in attendance to “prevent severe mental or physical harm to Zubaydah.[vi]”

Bybee goes on to claim that these methods, waterboarding included, did not result in “prolonged mental harm.” Because the tortured subject “may” be aware that they are not drowning despite the fact they feel like they are, the act cannot be considered torture because of the purported sanitizing quality of this possibility. Additionally, he focuses on the lack of physical pain involved in simulated drowning. He references his memo to Gonzales stating “’ pain and suffering’ as used I section 2340A is best understood as a single concept, not distinct concepts…the waterboard, which inflicts no pain or actual harm whatsoever, does not in our view inflict ‘severe pain or suffering…[vii]’”

[i] Jay Bybee, “Memorandum for Alberto R. Gonzales, Counsel to the President Re: Standards of Conduct for Interrogation under 18 U.S.C. §§ 2340-2340A,” August 1, 2002, 2–3, https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB127/02.08.01.pdf.

[ii] Bybee, 3

[iii] Bybee, 3

[iv] Bybee, 14-15

[v] Jay Bybee, “Memorandum for John Rizzo, Acting General Counsel of the Central Intelligence Agency Re: Interrogation of al Qaeda Operative,” Justice.gov, August 1, 2001, 1 , https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/olc/legacy/2010/08/05/memo-bybee2002.pdf.

[vi] Bybee, 3-4

[vii] Bybee 11

David A. Harrison

David A. Harrison is a working-class student and journalist originally from Tyler, Texas. A recent graduate of the University of Texas at Tyler, Harrison is now preparing for his post-graduate studies at the University of Texas at Austin. Having experienced poverty and houselessness throughout his childhood and adolescence, Harrison hopes to peruse a Ph.D. and a career in academia. There, he hopes to research and deconstruct the sources of socioeconomic inequality within policies, practices, and histories.